Even stories on cost of living leave journalists facing assault, threats and arrest under Digital Security Act

Four weeks ago, a reporter in Bangladesh was hauled from his office, badly beaten – and then thrown from the roof of his building, leaving him with fractures in his back, three broken ribs and a machete wound on his head.

The journalist, Ayub Meahzi, believes he was targeted for reporting on alleged local government ties to a criminal group.

The attack in Chattogram, also known as Chittagong, in south-east Bangladesh, has compounded fears of a further deterioration in press freedom in the country, which already languishes near the bottom of the annual global press freedom index, due to be published this week by the group Reporters Sans Frontières.

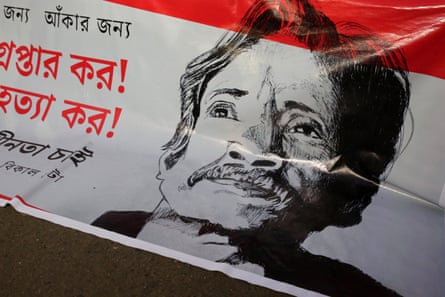

In late March, Bangladesh police arrested a journalist working for the country’s largest newspaper, Prothom Alo, for a seemingly innocuous report that went viral, on the subject of high food prices and living costs.

The reporter, Shamsuzzaman Shams, has been charged with producing “false news” and the newspaper labelled an “enemy of the people” by the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina.

Journalists and press freedom groups say the country has suffered since the introduction in 2018 of the Digital Security Act (DSA), a cybercrimes law the government says is aimed at stopping propaganda and extremist material online but which has led to dozens of arrests, as well as intimidation and violence against journalists.

Media workers say they have avoided critical stories on the ruling party or its projects, but the attack on Prothom Alo, which involved protests and intimidation by supporters of the ruling Awami League party, has emphasised how journalists can face repercussions for a range of issues, including damaging the “national image” or upsetting a minister or official.

“Reporting on issues like a price hike seemed harmless. But after the arrest of Shams, it seems obvious we can’t report on these seemingly innocuous issues as well,” said the journalist, who wished to remain anonymous.

They added that it was not only fear of facing a lawsuit under the DSA, but also the threats and intimidation journalists and their families face. “It’s a way of creating panic among journalists. These police arrests happen mostly in the middle of the night, and in some cases they [the journalists] are taken for a few days, and no one knows where you are.”

In 2021, the writer Mushtaq Ahmed died in custody after suddenly falling ill, nine months after being detained for social media posts criticising the government’s response to the Covid pandemic.

The cartoonist Kabir Kishore, who was arrested alongside Ahmed, said he had been tortured and that Ahmed had also spoken about receiving electric shocks.

According to the Digital Security Act Tracker, run by the Centre for Governance Studies in Bangladesh, there have been more than 600 cases filed against journalists using the law. Almost half of all cases filed under the law between October 2018 and August 2022 were by people affiliated with a political party or government officials.

“We didn’t know which pieces could land us in trouble. We didn’t have a clear picture of what might happen to us or our contributors, so we tended to exercise random, arbitrary judgment on which stories to run,” recalled Nazmul Ahasan, who worked on the opinions team at an English-language newspaper, the Daily Star.

“There were very ordinary pieces we declined to publish … you have to think twice before publishing a story on a mid-level police officer or ruling-party member of parliament,” said Ahasan.

Ahasan, who is now living in the US, said this had left many journalists considering their futures, with some looking to move abroad and others hoping that a change, perhaps through elections, could ease pressure on them. In the meantime, they avoid covering sensitive topics and tone down the language they use in reporting.

Riaz said many publications were owned by business-owners affiliated with the ruling party or who fear damage to their interests if they upset the wrong people. He said the country as a whole was suffering because journalists were scared of doing investigative work on issues such as corruption.

“Journalists no longer think: ‘This is something happening in front of me, whatever it takes I’ll find out who’s behind it.’ No, they think: ‘What’s the minimum I can write and stay alive?’”