(London) – Bangladesh’s human rights situation worsened in 2012 as the government sought to narrow political and civil society space, continued to shield security forces from prosecution for abuses, failed to investigate disappearances and killings, and announced stringent rules to monitor non-governmental organizations, Human Rights Watch said in its 2013 World Report released today.

In its 665-page report, Human Rights Watch assessed progress on human rights during the past year in more than 90 countries, including an analysis of the aftermath of the Arab Spring.

The practice of disguising extrajudicial killings as “crossfire” killings continued in Bangladesh, as did disappearances of opposition members and political activists. A prominent labor activist was kidnapped and killed, while other labor activists were threatened. Civil society and human rights defenders also reported increased pressure and monitoring.

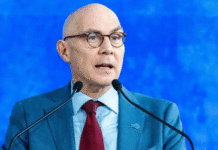

“This government came to power promising the end of extrajudicial killings, a liberal environment for activists and critics, and an independent judiciary,”said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “But the government no longer seems to even be trying to achieve these goals.”

Human Rights Watch said that while Bangladesh has a strong set of laws to tackle violence against women, the implementation remains poor. Violence against women including rape, dowry-related assaults, and other forms of domestic violence such as acid attacks, sexual harassment, and illegal punishments in the name of “fatwas” continue. Discriminatory personal laws continue to impoverish many women at separation or divorce, and trap them in abusive marriages for fear of destitution.

Workers in the lucrative tannery industry continue to suffer physically from terrible conditions inside the tanneries, Human Rights Watch said, causing both acute and long-term hazardous health situations, while regulations to ameliorate these conditions have gone unheeded.

One of the most disturbing trends in 2012 was increased pressure and monitoring of civil society. Non-governmental organizations, including human rights groups, reported increased threats, harassment, and intimidation. Several human rights groups, particularly those openly critical of the government, reported problems with registration and government blocking of funds for their projects. Several leading labor rights activists continue to face criminal charges, some of which carry a possible death sentence.

The government drafted a bill regulating foreign donations which has the potential to legalize the already arbitrary and non-transparent process by which the government regulates the receipt of foreign funding. Although not yet passed, NGOs reported that many of the cumbersome mechanisms in the bill were already being put into practice. In August 2012, the government announced plans to establish a new commission charged solely with regulating NGO activities, in addition to the already existing NGO Affairs Bureau, which continues to be accused of routine corruption by NGOs.

In 2012, Human Rights Watch welcomed a decrease in extrajudicial killings by the notorious Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), but the number of killings remained very high. Although an internal investigative unit was set up in 2012 to inquire into and prosecute RAB members, very little is known about what action, if any, this unit has taken. Independent observers reported that the offenses examined by the internal investigative unit are routine disciplinary offenses, and that more serious allegations of extra-judicial summary killings and disappearances remain unexamined.

“While government and RAB officials claimed that they held abusers accountable, it is still a fact that no RAB officer or senior official has ever been held criminally accountable for any of the well-documented abductions, torture, or killings carried out by RAB,” Adams said. “Even in the highly publicized case of the shooting of the school boy Limon, no one has been charged, yet the authorities continue to proceed with a flawed prosecution against him.”

Flawed trials against members of the Bangladesh Rifles accused of mutineering in 2009 continued. Human Rights Watch issued a report in July outlining credible allegations of custodial torture and deaths, as well as mass trials in gross violation of due process rights. Instead of investigating the allegations, the government simply dismissed them, with the then Minister of Interior flatly denying any abuses in a meeting with Human Rights Watch before reading the report. The government insisted that trials against as many as 800 accused at a time were procedurally sound, despite the fact that many accused had no assistance of counsel and in many cases were unaware of the charges laid against them. Many of these accused in ongoing trials face the death sentence if found guilty.

Glaring violations of fair trial standards became apparent in 2012 in the trials of the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), a wholly domestic court set up to try those accused of war crimes during the 1971 war of independence. One of the present government’s central campaign pledges in 2008 was to ensure that these long overdue trials took place. Human Rights Watch has long called for justice for victims in the 1971 liberation war. However, serious flaws in the law and rules of procedure governing these trials have gone unaddressed, despite proposals from the US government and many international experts.

All the ICT trials underway in 2012 were replete, with complaints from both the prosecution and defense. Each side accused the other of witness intimidation. In one apparently serious irregularity, the prosecution claimed that it was unable to produce several of its witnesses and asked that written statements be admitted as evidence, absent any direct or redirect examination. The court granted the request despite the fact that the defense produced government safe house logbooks which appeared to show that some of these witnesses had been in the safe house and available to testify. In one case, when on November 5 the defense attempted to bring one of these witnesses, Shukho Ranjan Bali, to court, he was abducted from the gates of the court house by police officers in a marked police van.

In December, The Economist published an article detailing some hacked email and Skype conversations between the chairman of the ICT and an external adviser based in Brussels. These communications revealed longstanding prohibited contact between the Chairman, the government, the prosecution, and the advisor. They showed direct government interference in the operations of the ICT. The publication of these communications caused the Chairman to resign, leaving a bench in which none of the three judges has heard the totality of the evidence against the accused. Motions for retrials in four of the cases due to these communications were rejected by the tribunal, calling into question its impartiality.

“The trials against the alleged mutineers and the alleged war criminals are deeply problematic, riddled with questions about the independence and impartiality of the judges and fairness of the process,” Adams said. “This is tragic, as those responsible for serious crimes could end up appearing to be victims of a miscarriage of justice. By dismissing all criticism out of hand without any real inquiry into them, the government shows it is more concerned about winning votes than about following the rule of law.”

The government flouted its international legal obligations in June 2012 when sectarian violence in Arakan state in neighboring Burma led to an influx of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh. The government responded by pushing back boatloads of refugees, insisting it had no obligation to provide sanctuary for them. The government also curtailed the activities of NGOs operating in pre-existing Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazaar.

“The government seems to view every critic, including reputable domestic NGOs, as part of some vast conspiracy to topple it, instead of organizations genuinely interested in improving the country,” Adams said. “This attitude of ‘you’re either with us or against us’ characterized its reaction to issues ranging from the war crimes and mutiny trials to responsibility for factory fires and labor rights.”

Source: Human Rights Watch