THE river delta that is Bangladesh has plenty of sand but few stones. As the country’s cities are yet to accommodate the majority of its 160m people, this is no small problem. The capital Dhaka, one of the world’s ten largest cities, has begun to rid itself of its one-buffalo town infrastructure. An estimated 35,000 people move to urban areas every week; an additional 53m people will be living in the cities by the middle of the century.

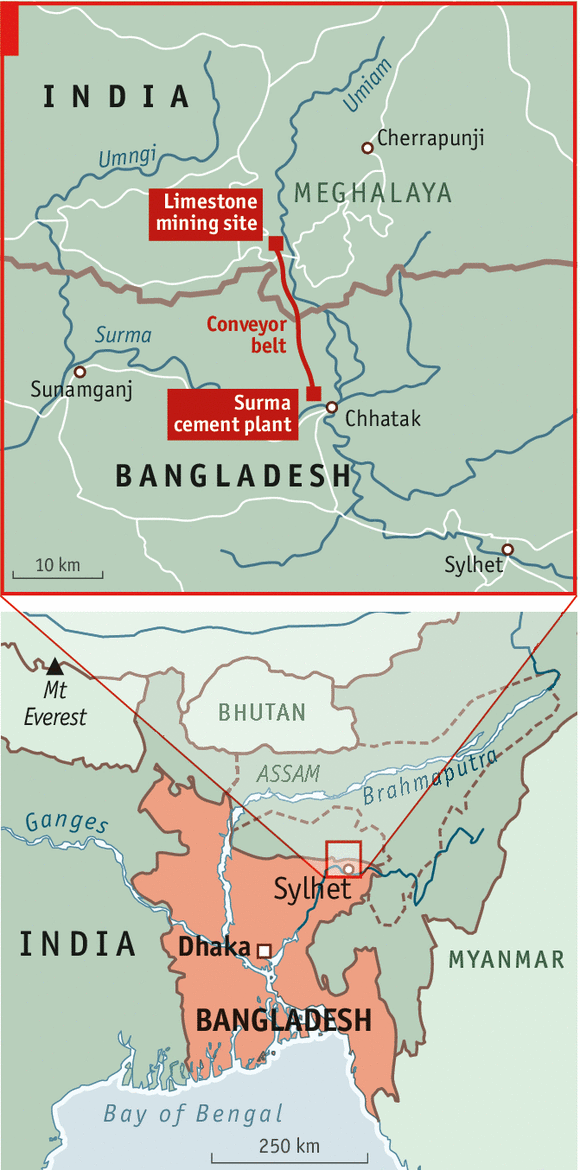

At one of Dhaka’s clubs for foreigners, a hangover from the days of aid-dependence, a man had told me about the engineering marvel that had sprung from this dearth of building material: a 17-km (11-miles) industrial conveyor belt in northern Bangladesh that carries in limestone from a mine on the other side of the border with India. It is apparently the world’s longest cross-border belt and only beaten in total length by a 60-mile-long belt that carries phosphate from a mine in Morocco to the coast.

To get anywhere close to it you have to take what foreign newspapers have dubbed “the world’s deadliest road”, because of the high rate of traffic accidents. It connects Dhaka with the town of Sylhet, the capital of a division of modern Bangladesh—at partition in 1947 its people voted in a referendum to leave Assam and join East Pakistan. Signs of unexpected prosperity lie in the rice fields along it: some houses belong to those the locals call “Londonis”, Sylhetis who made their lives in the United Kingdom and used their sterling to build houses back home, often in pink, blue and green.

West of the city of Sylhet, a smaller road descends into the Sylhet depression, a patch of land that sits on a sinking tectonic plate. The southernmost reaches of the Himalayas, the Khasi Hills in the Indian state of Meghalaya, come into sight. The mountain range absorbs much of the annual monsoon rains. In nearby Cherrapunji, in India, the average rainfall per year is 10m. Much of the water ends up in Bangladesh anyway; it floods the plains or flows down the Surma river and finishes up in the Bay of Bengal.

On the river’s northern bank near Chhatak lies the end point of the conveyor belt: it feeds a massive cement-making factory owned by Lafarge Surma, a French-Spanish joint venture. The plant’s output, cement bag by cement bag, glides down a curved metal slide into river barges bound for Dhaka.

A boy who runs a tea stall on the southern bank says business is brisk—the car-ferry and the plant run around the clock. It did not always used to be that way. For years the limestone had stopped coming. The Supreme Court in the Indian capital, Delhi, had banned the mining operation. Now environmental concerns, as well as those of the hill people, no longer stand in the way. The customers in the tea stall agree that it would be nice to have a bridge here. Khaleda Zia, a former prime minster, they say, started building one many years ago but her successor, Sheikh Hasina, did not bother to complete it.

The crossing by ferry costs Tk25 ($0.30) and after a two-hour wait and a five minute-ride we reach the other side. When it was built in the mid-1990s, the 1.2m-tonne-capacity cement plant cost $280m and was the biggest foreign direct investment in Bangladesh. Lafarge Surma says it helps Bangladesh save $65m in foreign exchange a year, pays more than $10m in annual taxes and provides thousands of jobs.

The plant accounts for nearly one-tenth of cement output in Bangladesh (of a total of about 15m tonnes) and serves a market that has yet to take off. Annual cement consumption there is 100kg per head, compared with less than 200kg in India and 1,000kg in China. Already the country imports 10m-15m tonnes of clinker every year—more than any other in Asia.

Following the 10km-stretch of belt on the Bangladeshi side proves tricky. The only road here resembles a dyke enclosed by water and it leads away from the belt. My stab at seeing the belt cross into India and climb up the hills ends at an outpost of the Bangladesh Border Guards where a friendly soldier says that this is a cul-de-sac.

Meanwhile, in Delhi and Dhaka, politicians have been praising each other and vowing to make progress on seemingly insoluble issues: how to share water, how to stop border killings and how to exchange enclaves and generally get along a bit better. They say trial runs for a bus connecting Dhaka with the Assamese capital Guwahati are imminent.

Surrounded and fenced off by India along a 4,100km-long border plus a high-security fence on its border with Myanmar, Bangladesh has long worked out a strategy of economic survival that relies on a minimum of regional integration—remittances by 7m-odd workers from the Gulf and exports stitched together by 4m garment workers for the EU and America bring in $35 billion in foreign currency. The conveyor belt remains, along with a power transmission link on the western border, the only manmade structure built after partition in 1947 that connects Bangladesh and India.

Source: The Economist