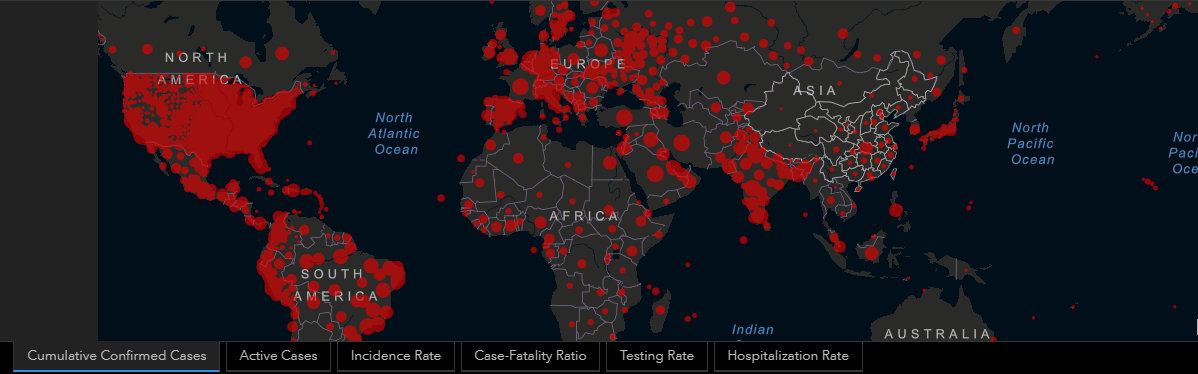

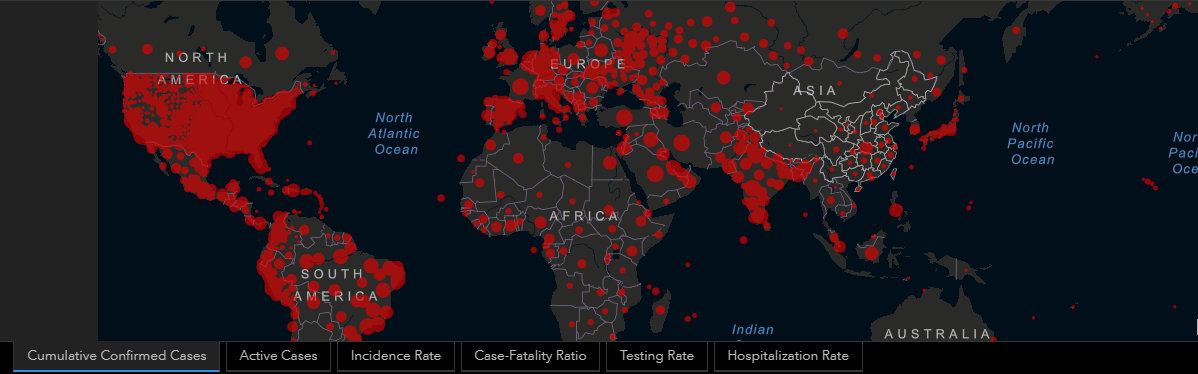

The COVID-19 pandemic is evidence that Russia and China have accelerated adoption of their age-old influence and disinformation tactics to the modern era. Previously, nations such as the Soviet Union had to prop up media outlets and place stories in newspapers around the world hoping they’d be picked up in English language outlets. Now, they just have to tweet, notes analyst Mark Pomerleau.

Adversaries have exploited U.S. laws and principles, such as the freedom of speech with online platforms, which makes outright banning accounts difficult. They’ve also targeted existing divisions within society such as protests over police tactics and racial equality, he writes for C4ISRNET (HT:FDD).

“[Adversaries] also are in a position where they can take advantage of a lot of the disinformation/misinformation that’s created right here at home in the United States by actual Americans who understand the language in a way Moscow couldn’t at a native level,” said Cindy Otis, vice president of analysis at Alethea Group, a start-up that counters disinformation and social media manipulation.

“[Adversaries] also are in a position where they can take advantage of a lot of the disinformation/misinformation that’s created right here at home in the United States by actual Americans who understand the language in a way Moscow couldn’t at a native level,” said Cindy Otis, vice president of analysis at Alethea Group, a start-up that counters disinformation and social media manipulation.

A case in point….

Since 2016, Russian disinformation campaigns have focused particularly on race and social issues related to African Americans, using proxy trolls in West Africa to exploit the fact that race remains a highly volatile area in U.S. politics, note analysts Žilvinas Švedkauskas, Chonlawit Sirikupt and Michel Salzer.

Their research confirms the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence conclusion that Russian information operatives were mainly targeting African Americans, they write for The Post’s Monkey Cage:

This past April, a CNN investigation discovered Russian troll farms in Ghana and Nigeria that employed African nationals to post content emphasizing U.S. racial divisions. American policymakers were startled by the fact that Russians had outsourced information operations to West Africa. House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff (D-Calif.) said that “the potential use of continental cutouts” to obscure Russia’s involvement “represents new and inventive ways to cover their tracks and evade detection.”

It’s important to recognize that disinformation efforts targeted at emotional beliefs could further decay the national discourse, say RAND Corporation analysts.

“When we think about memetic warfare, what’s really happening is we’re taking these sort of deep seeded emotional stories and we’re collapsing them down into a picture, usually it’s something that has a very, very quick emotional punch,” said Jessica Dawson, research lead for information warfare and an assistant professor at the Army Cyber Institute.

“They’re collapsing these narratives down into images that are often not attributed, that’s one of the things about memes is they really aren’t, someone usually isn’t signing them, going ‘I’m the artist.’ There [are] these really emotional punches that are shared very, very quickly, they’re self replicating in a lot of ways because you see it, you react and then you immediately pass it on.”

The European Union’s most recent response to disinformation contains one measure that deserves particular attention: a proposal to limit advertising placements on social media for third-party websites that profit off of COVID-19 disinformation. Imposing significant costs on bad actors in the form of lost revenue is one potential way to deter future aggression, DFR Lab’s The Source reports. RTWT

In Coda Story’s Infodemic, Katia Patin presents a few narratives — both real and fake, from Brazil to Bucharest — detailing how global disinformation is shaping the world emerging from the Covid-19 lockdown.