IN 1975, Sita Iyer was a 19-year-old college junior with a secret she was desperate to keep from her conservative, middle-class parents. Ms. Iyer, a Hindu, was in love with a Muslim. To avoid detection, she would meet her boyfriend, a dashing 23-year-old business student named Ayub Khan, in downtown Bombay, where she was sure no one would know her.

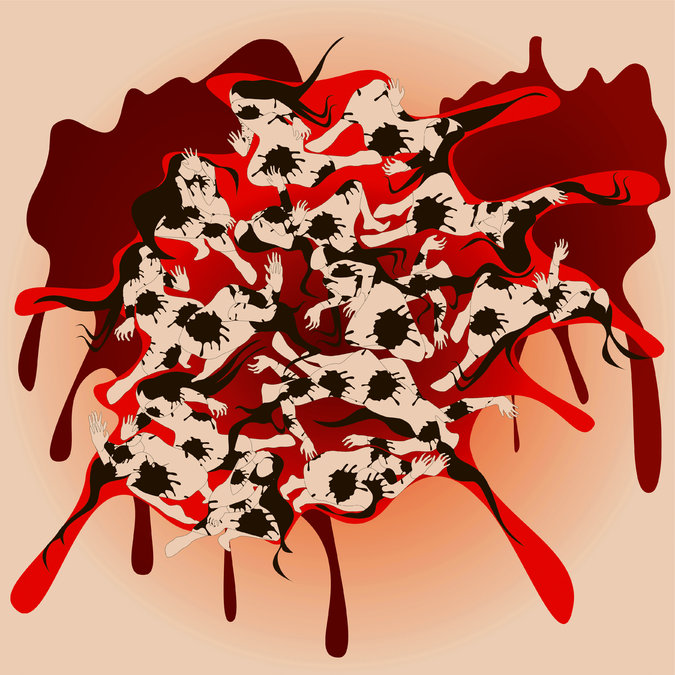

It was not quite 30 years after the Partition of India, a blood-soaked event that killed some one million people. India’s Muslims had been steadily ghettoized.

When the truth came out, Ms. Iyer’s parents were furious. “He will have four wives,” her father warned. “You will end up on the street.”

After she married Mr. Khan — and changed her given name to Salma — her family disowned her.

But looking back, she says, it was easier being an interreligious couple in the 1970s than it is in India today. At least she felt safe. Now, in contrast, the news is filled with report of assaults on mixed couples.

In several parts of the country, consenting adults who have broken no laws have been threatened, beaten up and, in a medieval twist, had their faces painted black by pumped-up bands of roving men who disapprove of Hindu women in relationships with Muslim men.

There have been reports of women being forcibly shoved into cars and dragged to police stations, from which they are made to phone their parents. Adult women, treated like chattel, like criminals and like juveniles.

Right-wing assailants have stopped weddings between interfaith couples from taking place. They have even forced married women to desert their Muslim husbands, and to marry Hindus instead.

The men behind these attacks are no mere vigilantes; they represent extreme right-wing groups with great political clout, such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the Bajrang Dal, and even the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

The violence coalesced around a supposed scheme known as love jihad — an oxymoronic term that first attracted media attention late in the last decade.

In 2009, Silja Raj, an 18-year-old Hindu woman in the southern state of Karnataka, eloped with a Muslim. Her father enlisted the aid of local right-wing groups to force her to return. These groups promptly declared that the elopement was part of a conspiracy to seduce vulnerable young women and convert them. The implication was that Muslim men had embarked on a war to Islamicize the womb of Hindu India.

An investigation commissioned by the High Court revealed that no coercion was involved. It also found no evidence of an organized plan to convert Hindu women. Ms. Raj, who had been made to return to her parents’ home for the duration of the investigation, promptly went back to her husband.

In subsequent years, right-wing politicians have used the boogeyman of love jihad in states with sizable Muslim populations like Gujarat and Maharashtra to present themselves as the protectors of Hindu virtue and win Hindu votes. Their behavior fit the descriptions of a hate crime, although no charges have ever been filed against them. They act as though the actions of any one Hindu woman are a reflection of her culture — as defined by politicians — and that it is the responsibility and the right of Hindu men to monitor these women and to meddle, violently, if necessary.

Though some prominent celebrities, like the Bollywood stars Shah Rukh Khan and Aamir Khan, are Muslim men married to Hindu women, the subject of interfaith marriage remains a sensitive one. But it has not, until now, resembled the debate around anti-miscegenation laws in America before 1967.

It was this summer, in the course of a hard-fought campaign in legislative by-elections in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, that the phrase “love jihad” entered the national rhetoric. The person responsible was a hard-line B.J.P. member of Parliament named Yogi Adityanath.

The state experienced clashes between Hindus and Muslims as recently as July, and Mr. Adityanath, a notorious rabble-rouser, fanned the communal flames. He spoke of the threat of love jihad in packed public forums with such urgency that it appeared he believed in this made-up term. In an interview on NDTV, a TV network, Mr. Adityanath said he would “not tolerate what is happening to Hindu women in the name of love jihad.”

The Election Commission reprimanded Mr. Adityanath for hate speech, but the term quickly gained an electric currency. It thundered across India’s TV screens every day. On Twitter, the term was trending with two hashtags (#lovejihad and #lovejihadexposed).

In September, the electorate rebuked Mr. Adityanath’s brand of politics, rejecting the B.J.P. in all but three of 11 contested seats in the state. But although he failed, his brand of poison has gained traction. Right-wing female demagogues have been reported as saying that Muslim men “force” women “to have two or three children,” that they “then leave her, or rape her, or throw acid on her if she resists, or murder her.” Pamphlets warning against love jihad have been found in college campuses and even at wedding venues.

This cynical ploy, love jihad, could have been constructed around money, or land, and in a country with a recent history of communal unrest, even self-defense, but it invoked women because the idea that women “belong” — as opposed to simply being — is one that is embraced by men of all classes and religions in India.

Even a poor man with few possessions feels he has something if he has a wife or a daughter whose destiny is his to control. Thus did a provocateur from the right-wing Vishva Hindu Parishad organization say, recently, that Muslim men “should leave our women and cows alone or be prepared for a massive retaliation.”

In fact, love jihad is not only a hate crime against one vulnerable community, Muslims, but another: women. If the women need protection from anyone, it is from these men who break the law and try to break the spirit of the women they claim to protect.

Ms. Iyer, now 57, and Mr. Khan, now 62, have two adult daughters who were brought up as Muslims. They are poster girls for a modern and liberal India. One of them lives in Munich with her German husband. The other, a journalist, lives in Bangalore with her Hindu husband. “Salma’s family only accepted us after our second daughter was born,” Mr. Khan told me. “But do you know something? Her parents have three sons-in-law, but once they got to know me they liked me the best.” His voice rumbled with laughter. “Her father used to be worried I would take four wives. It’s been 35 years, and I still have the one.”

Source: NYTimes