April 23, 2018 The Daily Star

Abuse of power abases innocent

PUBLIC HUMILIATION FOUND FREQUENT … A handcuffed man being taken to court . A group of onlookers congregate to see the prisoner while he keeps his face covered. Photo: Anisur Rahman

Inam Ahmed, Shakhawat Liton and Jamil Khan

Handcuffed and baffled, Rahim staggered out of the police lockup with 13 others. He felt a little dazed but no hunger although his last meal was 36 hours ago, his breakfast.

There was quite a crowd outside. He blinked his eyes to adjust to the afternoon sunlight. The waiting faces came into focus. His brother, wife with the little kid tightly clutching mother’s fingers, neighbours, his friend’s father and many other faces.

Suddenly Rahim felt lost. And shame as well which drowned him completely and yet he did not know why he should feel ashamed. To his best knowledge, he had not committed any crime. He runs an honest business, if running a 10 feet by 10 feet small motorcycle repairing shop could be called a business. Nor had the police told him why he had been detained in the Mirpur model police station for 36 hours.

But here he was. Just like a criminal, all handcuffed, standing before the whole crowd that although knew him to be an honest, innocent guy. And yet his image had now been shattered. His daughter gawked wide-eyed at her father who looked no different from the villains she watches in movies who get arrested in the end and are handcuffed.

Choron Soren, a Santal man, handcuffed to his hospital bed. Cops shot his legs earlier when he protested against police brutality. Photo: File Photo

“What has my father done? Murder? Smuggling?” her little brain whirred for an answer.

“Move. Get into the car,” the coarse voice of the police sub-inspector cracked in the air.

Still in his daze, Rahim walked involuntarily, like a robot; his feet no longer felt his own. He could not feel the touch of the ground.

Only after he got inside the police van, did he notice that the handcuff locked to another motorbike shop owner had clasped into his flesh so tightly that he was about to bleed.

He asked the policeman to unlock him because he could take the pain no more. The sub-inspector had a look at the hand and felt sympathy, for he helped ease down the handcuff.

The van, a Laguna as they call it, pulled out of the station compound. Another Laguna followed with six more of his friends all handcuffed.

Rahim found his wife weeping.

That afternoon turned all Kafkaesque for Rahim.

Journalist Probir Sikdar being taken to court in handcuffs, despite having to walk with crutches. Photo: File Photo

OC WANTS A QUICK CHAT WITH YOU

That afternoon actually began the day before, March 9.

Friday is usually a busy day for the bike workshops at 60 feet road of Mirpur’s Monipur. This is the day when people get a chance to get their bikes serviced for the whole week. A thorough cleaning, a little adjustment of the drive chain, checking the horn, changing engine oil.

From morning, Rahim and four assistants, all in their early teens and working without pay – for them two meals and learning the trade are worth the whole day’s toil from morning until late night, had no time to even sip a cup of tea.

“It is turning out a good day,” Rahim thought. He had promised his wife Masuda to buy a Saree this month. “Seems I can buy her the saree for sure.” A bike needed new shock absorbers, another needed new piston rings. They bring extra money.

As the Azan for Jumma rang out from the local mosque, Rahim finally could stretch his back that was hurting by now.

“You carry on the work. Let me come back after quick prayers,” he told his assistants and gave them some money for snacks.

Rahim then had a quick bath at home, put on a Punjabi over his jeans and hurriedly left for the mosque. After prayers, he stopped by his shop to see how the work was going before heading home for a quick lunch.

But just as he was talking to the boys, he heard a van stopping behind his back. The door opened and closed with a bang.

“Who is the owner of this workshop?” a heavy voice asked.

Rahim turned around and found himself face to face with a police officer, a sub-inspector.

“Me.””

“Get on the van,” the officer ordered.

“On the van? Why? What for?” Rahim felt lost.

“The OC (officer-in-charge) wants a quick chat with you. Let’s go to the police station.”

Rahim felt something creepy happening here. “The OC? What have I done? I am running an honest business. Why should I go to the police station? I have not had my lunch yet.”

“It will not take long. He just wants to talk to you about something. You can then go home and have your lunch.”

Believing his officer, Rahim said, “Ok. Give me five minutes.”

“Good. I will come back in a few minutes,” the officer went back to the van and whizzed away only to come back a little later. It was around 2 o’clock.

To Rahim’s surprise, he found the van crammed with some other workshop owners – 14 he counted later. None of them knew why the OC wants to see them.

At the police station, they were led into the duty officer’s room. The officer offered them chairs to sit and told them to wait.

“The OC is not here. He will come soon and talk to you,” he said.

One of the workshop owners wanted to know the reason for their summon to the station.

“I don’t know. The OC knows. Just wait for a few minutes.”

That wait stretched on for hours. Rahim and his fellow shop owners did not have lunch. They actually had no mood for lunch.

“When you are summoned to police station and you don’t know why you lose your appetite,” Rahim said. “We were baffled and apprehensive. We did not know what is waiting ahead.”

They were free to walk on the compound. Buy tea from the roadside shop. But they were warned not to leave.

Every now and then they wanted to know their fate and every time they received the same answer: “Wait. The OC is coming.”

Six hours later at around 8 in the night, they were taken one by one to the officer in charge of investigation.

“There have been some incidents of motorcycle hijacking in the area. What information do you have about the criminals? Do you know who are doing it?” the officer asked.

For the first time Rahim could see the reason why he and his fellow workshop owners had been summoned.

“I don’t know anything. I am just a workshop owner. I repair bikes. How can I know the criminals,” Rahim said.

The officer was not convinced. He kept repeating the question in various forms.

“Other workshop owners who are here gave me a lot of information. You must also know something.”

“They may know, but I have no information to share,” was Rahim’s short answer.

“Well, we will see,” the officer shook his head and called a constable. “Put him in the lockup.”

The constable held his hand tightly and led him to the back of the police station. Rahim felt numbed.

“What is happening? Why are they doing it to me?” he thought.

The constable opened the iron bar of the cell and pushed Rahim inside. Behind his back the door closed with a loud slam.

“So am I a criminal? For what crime?” the thought crossed his mind. “What will happen now?”

He found no answers. He felt numb and could not stand any longer. He let his body slump to the floor and lay there still.

That night, one by one all the workshop owners were asked the same question and then put in the lockup. They did not know what charges are being framed against them.

In a clear violation of fundamental rights afforded by the constitution, physically challenged Abul Hossain is escorted to court while handcuffed. Photo: File Photo

CHAT STARTS 8 HOURS LATER, ENDS WITH DETENTION

That Friday actually began the day before.

A motorcycle was stolen from in front of a high police official’s residence. Motorbikes are the easiest target for thieves and criminals.

They either stealthily take away the bikes or stop the riders at night and snatch away their bikes. Sometimes, the bikers are knifed or beaten up. In the last year 285 such incidents took place in Dhaka city. Very few cases are solved.

Recently, a few such incidents had happened in Mirpur and in one incident, the biker was killed. Police did little to either catch the criminals or recover the bikes.

But this time, it happened right in front of a high police official’s residence. So the official called the officer-in-charge and asked him to take action.

So on Friday, police made several rounds in the area and picked up workshop owners and motorcycle spares sellers like Rahim.

Their action is highly controversial. Because it was a random detention rather than collection of intelligence and specific action.

Even more controversial and illegal was what they did later.

Around 11 at night, the OC finally came.

One by one, the detainees were brought out from the lockup and brought before the OC. The same questions were asked and the detainees gave the same answers: We don’t know anything. And why are we kept here in the lockup without specific charges.

The OC listened sympathetically. He was friendly and well-behaving. “I know you are good businessmen. Don’t worry, once we check a few things you will be released in the morning. You may now go to sleep.”

But sleep did not come for Rahim that night. The policemen gave them rice and vegetables to eat. But none of them could take a bite. They did not feel any hunger.

The morning came and yet nobody bothered to set them free. By this time, their relatives had gathered outside with food.

They felt exhausted and hungry now. So they had breakfast. But time seemed an unending thing at the police station.

Finally at around 10.30, they started shouting. “Why are you not releasing us? Why is the delay?”

Around 3:00pm, there were a flurry of activities. The cell door was opened and they were asked to come out one by one. Relieved, Rahim stepped out. But to his surprise, he found his hand being handcuffed and tied to his fellow detainee.

By now he had sapped and had no energy left to ask why he is handcuffed and where being taken. Like a robot he walked on. Then he saw his wife and his daughter. The kid was wide-eyed and clutching her mother’s hand tightly.

Many cross thoughts were passing inside her small brain. Why is baba handcuffed? Suddenly the loving father she used to know had turned into one of those criminals she watched on Hindi movies. The criminals who after a long fight essentially give and get arrested. So, is Baba a criminal too?

His wife was silently weeping. Rahim remembered the Saree he had promised to buy her. A strange kind of anguish overcame him. He felt small and helpless.

“I would not look at them,” he told himself.

With a nudge from a constable, he got into a van with others.

His brother was there with his bike. “They are taking you to court. I am coming.”

As the two vans pulled out of the police compound, they were followed by their relatives on motorbikes. At the court, they were paraded inside the court building and into the lockup again. It was dark and crowded. Hot and stinking. People were talking but their voices sounded garbled in the high ceiling of the court building. Lawyers were walking by in black robes. Their clients trailing in doubtful steps. Here life becomes so uncertain.

After about one and a half hours later, Rahim’s brother came and said the court has given them bail. Rahim and the workshop owners finally came out of the lockup – free man again.

Nobody was talking much. There was not much to discuss. They just wanted to go back home, take bath and sleep. They just wanted to sleep away this nightmare. They even did not want to know what cases they have been implicated in.

FALSE CHARGES, MANY ANOMALIES

Much later, after he had a good sleep and much of the horror had waned that Rahim asked his brother about his case. And he was surprised to see what police said in their general diary document.

It was typed on an A3 page in small Bangla letters.

In that letter, the police said a tense situation had been prevailing in the area between two groups over establishing dominance at 5 o’clock. This could lead to killings as well, the general diary read. So to maintain order, police raided the area and found Rahim and others had ‘assembled to create trouble’. Therefore, they were picked up from the spot.

But in their ‘who-cares?’ approach, police made a mistake here. They forgot to remember that Rahim and the other 13 were already in police custody at 5 o’clock, the time they mentioned in the diary.

The Daily Star visited the spot from where they were picked up and talked to at least 20 people of the locality. None of them agreed that there was any tension between any groups and Rahim and 13 others accused in the police case maintain friendly relations.

Rahim further found that they were charged and arrested under Section 151 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

The mention of section 151 leads to another story.

Photo: File Photo

A NEW TOOL TO HARASS

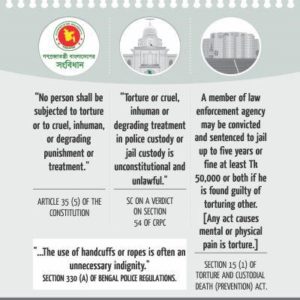

Much like the controversial and draconian section 54 of the CrPC, section 151 also gives the police wide and discretionary power to arrest and detain anybody.

Under section 54, police could arrest anybody just on suspicion that the person was planning to commit a crime.

But then this section has been widely abused by the police, the most sensational of it being the arrest and murder in custody of a private university student, Shamim Reza Rubel, in 1998.

His death in police custody caused a huge outcry that led to a legal battle against this arbitrary power of police. Finally, the Supreme Court in 2016 issued a guideline that restricted arrests under section 54. After this court ruling the use of this draconian law declined.

But then police found an alternative to harass people by applying the section 151 that gives police a similar arbitrary power to arrest anyone without a warrant if they feel the person was planning some offence.

And like Rahim, every day people are being harassed and traumatized under this law, the number of which is unknown as the prosecution does not keep any record.

Forget the torment Rahim had to bear from the moment he was picked up on that Friday noon, his agony continues even today. And so does that of other workshop owners’.

“I cannot forget that I was dragged along in handcuffs in front of the whole world,” Rahim says. Then he lightly lets off the most damning observation. “We thought police are supposed to protect us from thugs and mastaans. But now we have to think of how to protect ourselves from the police.”

The way police behaved with Rahim and others not only had violated their fundamental rights guaranteed by the constitution but the police regulations as well.

Section 330 (a) of Police Regulations prohibits using strict measures by saying the use of handcuffs or ropes is often an unnecessary indignity.

“Prisoners arrested by the police for transmission to a magistrate or to the scene of an enquiry, and also under-trial prisoners, shall not be subjected to more restrain than is necessary to prevent their escape. The use of handcuffs or ropes is often an unnecessary indignity,” it says.

In case of Rahim and his friends, there was no question of them escaping and so the handcuffs were just a show of raw power.

If one looks at the constitution, Article 35 (5) of it clearly states: “No person shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment or treatment.”

All these happened to Rahims. They were mentally tortured, they were inhumanly behaved by throwing them in custody without any valid reason under false charges.

Such police actions are a criminal offence under the Torture and Custodial death (prevention) Act 2013, according to legal experts.

The Indian Supreme Court has long ago issued guidelines restricting the use of handcuffs by police. In 1980, it ruled that the practice of routine handcuffing be strictly stopped immediately.

“Handcuffing is prima facie inhuman and unreasonable. It should be used only when the person is desperate, rowdy, or is involved in a non-bailable offence,” it said.

“The only circumstance which validates incapacitation by irons –an extreme measure– is that otherwise there is no other reasonable way of preventing his escape, in the given circumstances. Securing the prisoner being necessity of judicial trial, the State must take steps in this behalf. Heavy deprivation of personal liberty must be justifiable as reasonable restriction in the circumstances,” the Indian SC said.

Officer-in-charge of Mirpur model police station, Nazrul Islam, however vehemently defended actions by police against Rahim and others. He claimed they picked up the workshop owners based on information that a tense situation prevailed in the area.

BAIL AT LAST, FOR A PRICE

Protection and freedom comes at a price and it began from the day Rahim was dragged to the court.

“My brother had to hire three lawyers for my bail,” Rahim says. “They charged Tk 2,300 for the bail. All the shop owners who were taken to the court had to pay lawyers separately.”

His income from the workshop for the Friday was gone because in his absence no work was done. The next few days, Rahim just stayed home, hiding from everybody, not even receiving any call. His greatest worry was how his in-laws would react if they get to know about his arrest.

“I just thought how could I show my face to my in-laws. How will my father- and mother-in-laws take the news of their son-in-law getting arrested for motorcycle theft?” Rahim said.

So those days he stayed home, his income was lost. And now he has another hearing of the case coming up. This means another day lost and hiring lawyers, which naturally means more money to be spent.

“Tell me how long I have to run to the court? I am a poor man. How can I bear this expense? When will it end?”

Nobody knows when it will end for Rahim and others, and that depends on the police. At the end of the police report, it is written that after a thorough investigation police will submit another report on their involvement in the purported crime.

Now that made the case a hanging sword. It could swing either way. If for one reason or another police wanted to put them into further trouble they could write anything in the report as they did in the first instance. In that case their bail could be cancelled and implicated in another case. On the other hand police could write a truthful report and help them return to normal life, but then “truth” may require some investment.

DISMISSAL

For them, another nightmarish day was set on April 1, the first day of the hearing of their case.

Rahim could catch very little sleep on March 31 night. He got up before anybody else with butterflies in his stomach.

“What if the bail is cancelled? What if the police link me to some crime?” the thoughts ruined his appetite for breakfast.

By 8 am he came out of his house. A microbus they had hired the night before was waiting in front of their workshops. All the 14 accused crammed into the vehicle and reached the court at 9.30 am.

They signed some papers at the chamber of the lawyer they had hired for Tk 5,000. The lawyer left for the court with the signed documents.

For an hour, Rahim and the other workshop owners sat silently in the lawyer’s crammed room.

Then the advocate came with a smile: “Okay. Police submitted a report to the court saying they did not find anything wrong against you. Your case has been dismissed. You may go home.”

Rahim slowly came out and got into the microbus again. The court had cleared him, but will the society? he thought.

[Rahim is not real name of the victim. For his protection we refrained from disclosing his name in the report.]