WHEN I go to buy my drinking water, I don’t ask for water. I ask for Nestlé. Then I drive home with five 20-liter plastic bottles and make sure that we make every cup of tea, and all our ice, from this water. Like other people in this city, I believe the tap water is poisonous. During the summer, many of us follow the practice of putting out a water cooler on the street for passers-by. There are chic restaurants, cafes and art galleries in my neighborhood, but not a single public source of clean drinking water. Street vendors, security guards, trash pickers and maids rushing from one job to another often stop by to have a drink from this cooler. Like most such water coolers, mine is secured with a padlock; even the plastic tumbler is tied to it with a small chain.

Ramzan, the holy month of fasting known as Ramadan in the Arabic-speaking world, started last week, and like everyone else, I stopped putting out the water cooler. I did think about the people who wouldn’t be fasting and the non-Muslims not obliged to fast. But I didn’t think much. I removed the cooler because everyone does. There is the Respect of Ramzan Ordinance, which says you may be sent to prison for a few months if you eat or drink during fasting hours, or if you give someone something to eat or drink. I don’t really think I removed the cooler for fear of the ordinance: God knows, like every middle-class, privileged Pakistani, I flout enough laws. I did it because it would hurt the sensibility of those who fast.

Many of the 1,000 people who have died in the recent heat wave in Karachi died because of this sensibility: Some people were reluctant to ask for a drink of water, others were reluctant to offer it to them. You can’t blame them. Even if they could get past their inhibitions, there was no water to be had. All the little tea stalls, roadside restaurants, small juice or snack vendors disappear from the streets during fasting hours. In this month you can walk miles without finding a sip of water. And Karachi has developed in a way that you can also walk miles without finding any shade to cool down. Trees have been cut down to widen roads, overpasses have gobbled up footpaths; there are few shaded bus stops. Without water and without shade, while fasting or pretending to fast, people going to and coming back from work just fell on the streets and died.

Karachi is known for killing its residents, but weather had never been its weapon of choice. It is the world’s third-largest city, and its population has nearly doubled in the last 15 years, to 20 million. People come here to survive even though they know it can be a dangerous place. They leave bombed-out villages in the tribal north or parched hamlets in South Punjab to come settle at the edge of sewers in unplanned slums and make a living, mostly in daily wages, building malls or guarding them. Karachi hosts refugees from countries as diverse as Afghanistan and Myanmar. One reason so many have flocked to the city is that the weather has always been hospitable. You can sleep on the streets year round. Winter is only a rumor. Summer is hot and humid, but usually bearable out in the open with the breeze from the Arabian Sea.

The highest recorded temperature during the current heat wave in Karachi was 45 degrees Celsius, or 113 degrees Fahrenheit. Other towns in Pakistan have recorded temperatures of 50 degrees Celsius, or 122 degrees Fahrenheit, without ever suffering the kind of catastrophe that struck here. The victims, mostly poor and working class, needed some shade, a drink of water and a bit of time to slow down. But shade and a respite from work are hard to come by in Karachi — even in the month of Ramzan, the work of being a megacity must go on.

Thousands of construction workers dangle from high-rises. Traffic constables stand on city squares. Private security guards sit outside banks and offices. All in the heat, with no shade. When it is not Ramzan, these workers usually carry a bottle of water. When it is Ramzan, they don’t. When it is Ramzan, the eateries where they could score a free drink are shut. And when it is Ramzan, all the kindhearted people take away their coolers.

Since an overwhelming majority of those who died were poor, nobody is calling for an investigation or rethinking how the city is growing. The victims were just dehydrated and not sensible enough to protect themselves against the harsh weather. They don’t count as martyrs, according to religious authorities, even though they died during the holy month, many of them while fasting. The media express indignation, but over power breakdowns: the assumption being that with enough electricity these people wouldn’t have left their air-conditioned rooms and would have had chilled water to drink. Just as we kindhearted people do.

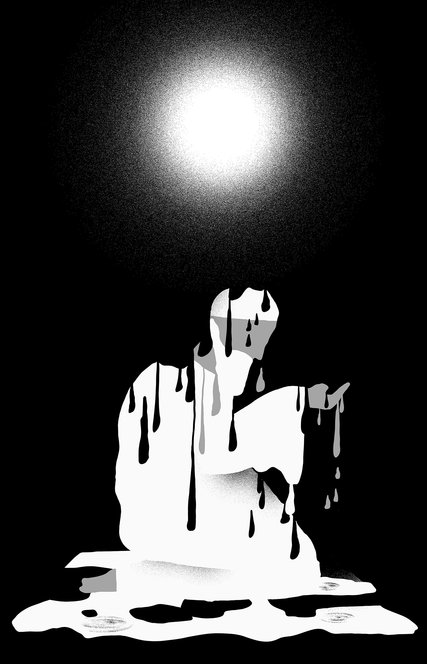

But it really wasn’t the lack of electricity or even the heat that killed these 1,000 people. What killed them was the forced piety enshrined in our law and Karachi’s contempt for the working poor. These people died because we long ago removed any shade that could shelter them from the June sun and then took away their drinking water. When they were about to die, we rushed them to hospitals in ambulances paid for by charities and gave them medicines paid for by charities. We gave them white sheets to recuperate in if they survived, and when they didn’t, those white sheets became their shrouds. Karachi’s hospitals are now awash with chilled bottles of Nestlé water donated by the kindhearted people of the city, but you still can’t get a drink of water on the streets.

Mohammed Hanif is the author of the novels “A Case of Exploding Mangoes” and “Our Lady of Alice Bhatti.”

Source: NYTimes