Afsan Chowdhury

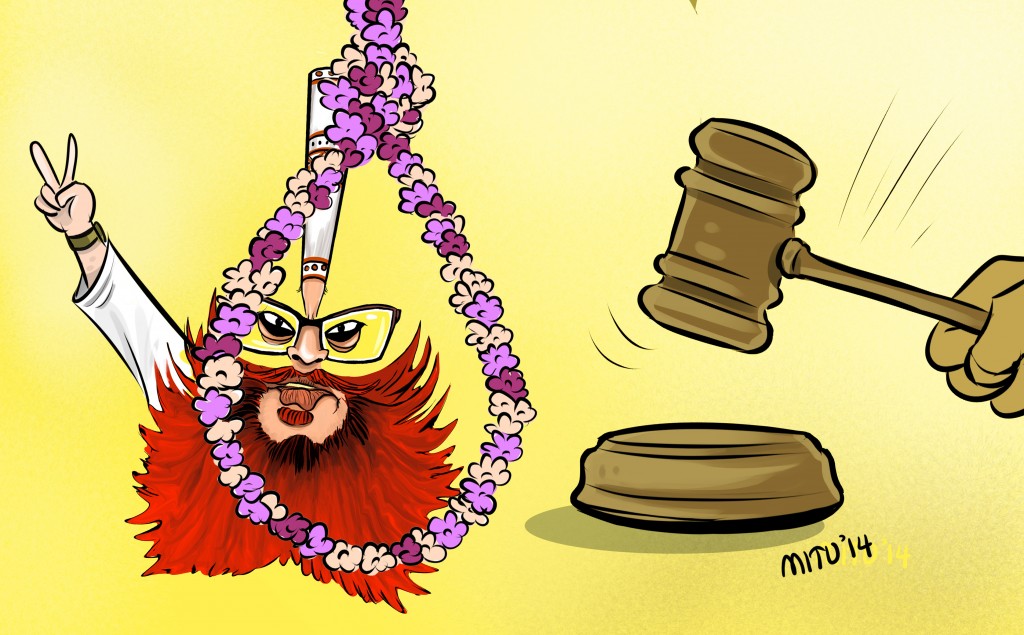

The reduced sentence of Delwar Hossain Sayedee has come as a shock to many. Many even feel that he has been allowed to go ‘free’. But have the trials ever been a matter of legal justice? To most the war crimes trials were to formalise nothing but revenge seeking and following due process was not the primary issue. The Shahbagh Movement that erupted as a result of dissatisfaction over Quader Mollah’s verdict led to legal amendments asking for appeal against lesser sentences by the prosecution and he was duly hanged after the appeal. In Sayedee’s case, the appeal has been upheld and sentence reduced showing that time and politics apart from legal circumstances have also changed. What does it mean actually?

* * *

The rules of political game have changed substantially since the trials had begun. Happening just before the elections, there were a lot of objectives beyond the trial, including dumping the BNP out of political scene. While the 15th amendment clearly put BNP on the defensive, the war crimes trials were an extra hammer to hit home as it involved its main ally — Jamaat-e-Islami. AL opponents also hoped to use politics around the trial to their benefit by creating an upsurge but despite the violence, AL steered through and created a negative brand for the opposition around violent protests. But its biggest problem came from the people who banded together and refused to accept the verdicts passed by the court. For a period of time, AL was uncomfortable when the simple business of the trial slipped into treacherous political waters as public expectation of hanging following every trial met with disappointment. Quader Mollah verdict exposed the fissure leading to the rise of Shahbagh Movement and cast some shadow over the AL’s declared intent of being the only political party bearing the ‘chetona’ of 1971.

* * *

Shahbagh was challenging a legal verdict protesting from the street. What it also did was challenge the jurisdiction of the court and the premise of the legal supremacy of the trying court. However, this is not the first time that it had happened and we are reminded of the 1969 events when Sheikh Mujib was accused of treason in the Agartala conspiracy case and the public took to the streets and at some point torched the courtroom and the judges fled away. In the end this very court case triggered the final phase and ended Pakistani rule in 1971. What it also means is that our legal system has often been used for political purposes and sometimes the situation can go out of control. In 1969, the evidence was not important. The public perception that Sheikh Mujib was not guilty was the only important thing. In 2013, the evidence was not important. The public perception that all the accused were guilty was. In both cases, the conflict between perception and law was acute.

* * *

The public was not looking for a fair trial but revenge. Having been denied any opportunity for justice for what was done in 1971, they saw the war trials as a tool for exacting blood for blood. Thus the concept of trial itself faced challenges and the work of the judiciary was not the same as that of the public. What people wanted and what the courts could give were not the same. In that sense, Shahbagh represented public sentiments better than the WCT. In the end, the issue was political rather than legal.

* * *

The government didn’t expect the explosive rise of public sentiment through Shahbagh initially. As it threatened to become an independent political space, the government party quickly adjusted to the situation and by taking several measures including provisions for enhancement of sentences wrested the initiative. The Ganajagaran Mancha very rapidly peaked but also lost its independent space and was soon overrun by the AL’s political machinery. The AL displayed the political maxim that organisational strength can overtake ideological enthusiasm anytime. After cobbering the Jamaat-e-Islami as its movement died and the BNP left out in the cold, it even ensured that the Mancha and its leaders were not able to acquire an alternative space. It has become the only political reality for the moment.

* * *

Yet the critics of AL have strong opinions regarding the intent and behaviour of AL. Author and activist Salim Akbar, Beer Prateek, has this to say on the situation. “It was all a set up. Hanging was announced earlier to get votes and become popular. Now AL wants to stick to power at any cost, so an ‘arrangement’ with Jamaat is necessary and thus the verdict by the Supreme Court. Justice in this country, I am afraid is for sale.”

He was responding to the issues we had raised with him.

a. The trial was fair but the verdict was wrong.

b. The Appellate division illegally saved Sayedee.

c. Any sentence which enhances punishment is fair and any that reduces is not.

d. If hanging is the only sentence acceptable, is there a need for trial?

By answering each question, people can obtain their answer but no matter what the questions are, the answers will be different reflecting political fragments around.

* * *

Appeals will be on but the matter has probably been resolved. The chances of another Shahbagh are remote. The activists who gathered for an encore after the verdict announcement have been scattered by police batons and water cannons. It’s a far cry from the heydays when the light from rebellious candles lit up the city. Today, the street belongs to the government in power and they have effectively ended all opposition surrounding the trials. Instead of being pushed by streets which challenged a legal decision, the latter is now supreme. No matter what the grievances are, the official verdict will has been asserted. BNP, Jamaat, Shahbagh have all been driven out of the political space. It’s not what has happened or hasn’t happened to Delwar Hossain Sayedee at all. It was about the triumph of the AL and its laughing all the way to the victory podium.

Source: Bd news24