In “Regarding the Pain of Others,” Susan Sontag writes, “being a spectator of calamities taking place in another country is a quintessential modern experience.” In Bangladesh, it appears that we are the spectators of — and collaborators in — our own calamities. Every few months, we witness a major tragedy, knowing all the while that once the dust has settled on the terrible thing that just happened, it is only a matter of time before another one is splashed across the front pages of our newspapers.

Take August, for example. It was Eid al-Fitr, the celebration that marks the end of the fasting month of Ramadan. Thousands of urban migrants left the squalor and promise of the capital city, Dhaka, and returned to their villages to be reunited with their families. The village homes they traveled to were far away, so they boarded ferries to cross the major rivers that bisect the country. They spent a few days at home, and then began to make their way back to the city. They boarded the same ferries.

One, the MV Pinak-6, waited at Mawa port in Munshiganj district, about 20 miles south of Dhaka. At around 2 p.m., the ferry began its two-hour journey across the Padma River. Because ferry passengers tend to be poor (wealthy Bangladeshis prefer to remain in the city and rejoice at the easing of traffic), no one counted the number of people who climbed aboard. The migrants crowded onto this particular ferry because no one knew when the next one would arrive, and they needed to rush back to their jobs.

And then it happened: The ferry capsized. Scores, perhaps even hundreds, drowned in minutes. The Pinak-6 was licensed for 85 passengers, but was reported to be carrying more than 200. In addition, its operating license had actually expired. The trip occurred at high tide, under a weather warning: Just 10 minutes before the ferry was due to arrive, the shore visible, it tilted over and sank rapidly into the riverbed. Only a few dozen were able to swim to shore, or were rescued by locals. There were 110 survivors, and so far more than 40 bodies have been recovered. The rest of the passengers disappeared without a trace.

The Padma is swollen by monsoon rains at this time of year, and the Pinak-6’s wreck has not yet been located. Ferry disasters happen regularly in Bangladesh — the last one was just a few months ago, in May. Over time, the stories echo one another and become banal. Overloaded boats. Two hundred people on board. Women and children. People waiting on shore for news of their loved ones. A search begun, then called off.

Last month, I wrote about the affection that Bengalis have for their rivers. They do, but the other truth is that the riverbed is lined with bodies, drowned in the face of an indifferent state.

And ferries are not the only way to die when trying to get from one place to another in Bangladesh: Our roads fare little better. The World Health Organization estimates show that at least 17,000 people die on Bangladesh’s roads every year.

One of these roads, the Dhaka-Sylhet highway, has been dubbed the deadliest road in the world after a World Bank-funded project to upgrade the highway placed priority on speed but not on safety. Now that the road is smooth, cars and trucks can barrel along at many times the speed limit,raising the death toll. Many of the dead are not even drivers; they are those who cannot afford any form of transportation, and get mowed down by passing vehicles while walking alongside the highway.

We have become a country that takes disaster in its stride. We take for granted that, every year, a certain number of people will die for entirely avoidable reasons, killed on roads that could have been safer, drowned on ferries that were overcrowded. At some point, someone, or a collection of people, have made the decision that the cost of upgrading, maintaining and regulating our transportation infrastructure is higher than the cost of the lives that will be lost if things continue as they are.

What is at stake here is not just the loss of individual lives, but the very basis of our social contract. We are saying that some lives are not worth spending money on, because there are others who will always have ways of avoiding disaster. They will board giant, tank-like cars or private helicopters or expensive cross-country flights. When some of us no longer have to use the roads or board the ferries, the roads and the ferries do not need to be safe.

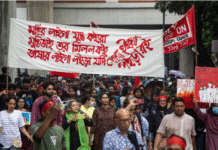

When the Pinak-6 capsized, we looked at photographs of the families waiting on shore for news of their loved ones. We read angry editorials and Facebook posts. But in all likelihood, this disaster will go the way of all the others that came before. No minister will be fired, no regulation will be enforced, no prosecution will be handed down.

And we will become a little more inured to our disasters. We will say, well, it could have been worse. It could have been a cyclone. The dead could have numbered in the thousands, rather than the hundreds. So we move on. And our social contract gets a little cheaper, a little more brittle.

When we watch another person in pain, an image meant to provoke empathy, we are also acknowledging that this person is not us. The greater the tragedy, the more we feel ourselves separate from it, because we would never be on that ferry, or in that garment factory when it collapsed, or on the side of that road when the car struck. To paraphrase the aesthetician Elaine Scarry, in “The Body in Pain,” the larger their pain, the greater our power. The question remains: What do we do with this power?

Source: The New York Times