Last update on: Sat Aug 19, 2023 12:34 PM

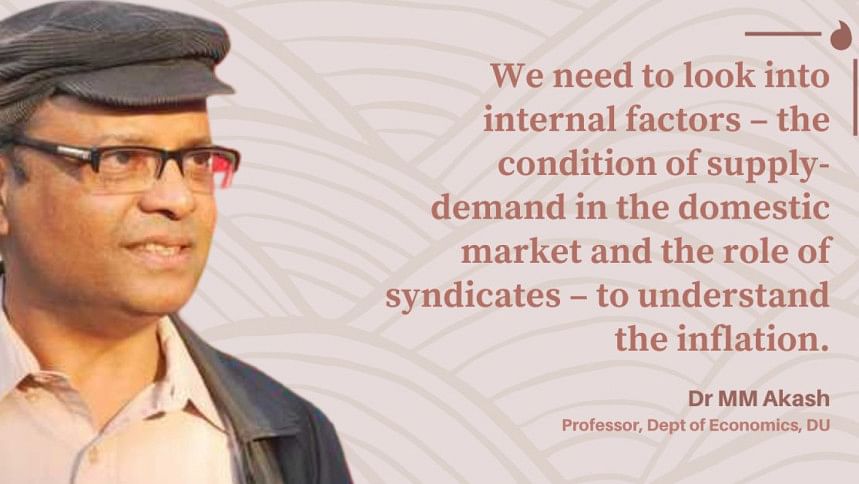

Dr MM Akash, professor at the Department of Economics in Dhaka University, discusses the ongoing challenges in Bangladesh’s financial sector in an exclusive interview with Naimul Alam Alvi of The Daily Star.

Bangladesh is now experiencing another bout of price hike of essential items, and our average inflation is still over nine percent (as of July 2023). Why do you think this is happening?

The ongoing inflation in Bangladesh has two sources: external and internal. If prices of the products that we import increase, our economy will naturally experience inflation. But let’s look at eggs – they’re not a product we import. Why are they getting costlier, then? We need to look into internal factors – the condition of supply-demand in the domestic market and the role of syndicates.

Producers as well as the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock say there is no considerable issue in the supply and demand of eggs. So what explains the current state of the market? There could be two possible reasons behind this issue: there is a monopoly or some sort of syndicate at play, and/or there are too many middlemen in the supply chain.

Even for imported products like edible oil, wheat and sugar, besides our primary source India halting their export, there are allegations that local importers of these products control a large share of the market. So, they have the power to disrupt the supply and create a controlled crisis in the market, and make profits by selling the products at premium prices. Our Commerce Minister Tipu Munshi also voiced similar concerns, suggesting that he knows some of the wholesalers that control imports. So, why is the government not being able to force them to release these hoarded supplies? I blame misgovernance and mismanagement as the primary reasons behind our heightened inflation.

According to Bangladesh Bank, the taka depreciated 13.3 percent against the US dollar in 2022. The depreciation rate does not seem to slow down this year either. What are your thoughts on this?

The taka’s depreciation against the dollar is also fuelled by mismanagement on our part. We are failing to contain hundi or prevent money laundering. Currently, our national account deficit is increasing because of two reasons: one is obviously increased import bills, and the other is foreign credit loan interest. Our export earning is currently not sufficient to balance out these expenditures. So, we are forced to dip into our foreign exchange reserves.

On top of that, new money has been injected into the economy as of late. Our budget is in deficit, and the government is failing to collect taxes. So, they are asking the Bangladesh Bank for loans. And the Bangladesh Bank has essentially printed additional money – with no production against it – to compensate for that. As this extra money enters the domestic market circulation, it’s fuelling the price hikes.

Our banking sector’s total risky loans amounted to Tk 377,922 crore at the end of last year, per media reports. How much does this affect our economy and inflation?

The problem is that banks are giving away too many loans, and a large portion of those loans is issued to big companies, which are practically holding the banks hostage. If these big borrowers don’t pay back, and the banks sue them, they can just drag the cases. Getting property confiscation orders doesn’t help the banks much either, because the money doesn’t return but the banks get burdened with properties that practically have no sales or productive value, and those big borrowers will just leave those properties documented under the banks. It’s kind of a mutual hostage situation between the banks and big borrowers. The two parties don’t try to bother each other. On top of that, there are possible political factors at play: how much political influence a big borrower has impacts how much it will be bothered. Amid all this, the loans remain unpaid. The Bangladesh Bank is supposed to have a certain amount of reserve against these loans. Instead, we see that to “manage” the situation, it allows loan rescheduling, which in turn makes the big borrowers eligible for more loans.

All this loaned money is not being used productively. That’s why they are not being able to repay the banks, right? It can happen in two ways: one, they are not being used efficiently, and whatever they are producing is not selling much; or two, they are not used for the stated reason at all, and instead are used for activities that the borrowers cannot document. This illegally used money becomes black money, and to turn it white, they launder them overseas.

So, a large amount of money is wasted unproductively, and because of repeated bad loans, there is an extra supply of money in the market, which further increases inflation.

While announcing this year’s national budget, our finance minister said the annual average inflation was expected to drop to around six percent. Have you seen any effective policy changes or actions to support this aim?

That was basically a pious wish. They don’t have adequate preparation to contain inflation. The government needs to have one-third of the supply share in stock to have enough control over the market. If the price of any product shoots up, the government can have an open market sale to control it, and if the price depreciates, the government can buy the product in bulk and raise the market price accordingly. For instance, the government could buy paddy at a procurement price, and sell rice in the open market, and with the one-third supply share they should have, they could balance out the price throughout the supply chain.

What about the extremely vulnerable and low-income groups? How can the government help them?

The government should prioritise ensuring access to food and essential needs for the most vulnerable groups, without taking any payment from them. India, under their right to food policy, has adopted such a strategy to provide food for their most vulnerable groups against minimal prices. If our government ensured a large share of stored supply in their control, as I’ve mentioned already, they could’ve organised open market sales at low prices, and also provide essential commodities for the vulnerable.

The government is providing ration support for some sectors, considering them essential priority groups, such as those in defence, law enforcement, and government administrations. This should not be the priority order. Even from a purely economic perspective, it makes more sense to prioritise ration for the garment workers, and the whole labour force first.