Well-known civic rights activist Mizanur Rahman’s narration of his harrowing experience of being picked up by police and tortured under custody, published in this newspaper’s online version on June 15, gives us some disturbing snapshots of the unlawful actions of our law enforcement agencies. As a keen follower of developments related to human rights, I am reminded of the term used by the Committee Against Torture (CAT) of the United Nations for these kinds of arbitrary and unlawful abductions by members of law enforcing agencies. It’s called “unacknowledged detentions.” Though Mizanur’s four-and-a-half-hours-long unacknowledged detention came to an end to the relief of his family, the pains and psychological distress he suffered would no doubt stay with him forever.

Is this unacknowledged detention of Mizanur an exception or deviation in policing practices? Unfortunately, recent trends suggest it has become a preferred tactic to bypass the mandatory legal requirement of producing the suspect before a magistrate within 24 hours. People disappear like characters of a fictional thriller and, if luck favours, they reappear, shown arrested just hours before from some strange place and produced before a court with a petition for remand. The UNCAT, in its concluding observation published on August 26, 2019 said, “The Committee is seriously concerned at numerous, consistent reports that the State party’s officials have arbitrarily deprived persons of their liberty, subsequently killed many of them and failed to disclose their whereabouts or fate. Such conduct is defined in international human rights law as enforced disappearance, whether or not the victim is killed or reappears later.”

In Mizanur’s case, when police picked him up from Bikrampur Plaza, he was misled into believing that it would be just a normal chat with the Deputy Commissioner. But soon he realised that something was not right and managed to inform his daughter. Soon afterwards, he was surrounded by several other police personnel and huddled into a car. In the car, they started misbehaving with him and snatched away his mobile phone. While his family members contacted the local police station, Shyampur Thana, law enforcement members expressed their ignorance about his detention. Though, at that time, he was either in their custody or was just being handed over to the Detective Branch (DB).

Unlike other victims of unacknowledged detention, Mizanur gave a vivid description of the demeaning behaviour he was subjected to by a senior officer at the Shyampur police station and the physical torture he had to endure there. In his words, “At one point, the female officer ordered that I be beaten up. A policeman was standing there with a stick. Once ordered, he beat me hard several times.” He added, “I have so far fought a lot to live with self-respect. Being beaten like this was unacceptable to me. Yes, I have been beaten up before on the road while protesting some cause. But being beaten up like this just for saying something really hurt my self-respect. I could hardly speak. I had never felt so helpless. It also enraged me,” he said. He was not allowed to drink any water and was kept standing the whole time (about an hour) at the police station. He was threatened with the possible arrest of his wife and daughters as they too sometimes stood by him during civic protests.

Afterwards, Mizanur along with another arrestee were handcuffed, blindfolded and taken in a car to the DB headquarters. His blindfold was only removed after he was taken to a high official’s office there. But, there too, he was threatened that he could be falsely implicated in cases such as illegal possession of yaba. Later, after another three hours of mental agony, his family was called in and he was finally let go, most likely as a result of the alarm raised by other social activists and the constant enquiries from the media.

Many of us, including his family, had felt relieved that he was lucky enough to have been found alive and freed, unlike many other victims of enforced or involuntary disappearances. Thereby, not many voices have sought accountability of the officials responsible for his unlawful abduction or unacknowledged detention and torture under custody. Mizanur’s detention was the precise kind that was unacknowledged, as there won’t be any official records of police ever picking him up without a warrant, interrogating him without the presence of his lawyer, subjecting him to dehumanising or cruel behaviour and beating him under custody, keeping him blindfolded and hand-cuffed. All these acts are defined as torture under our law.

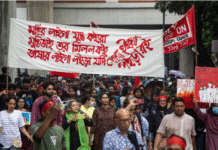

It all happened despite the fact that Mizanur was not a suspect for any criminal acts or named in any cases anywhere in the country. He is, however, famous for his unique protests demanding safe drinking water from the supplying authority, Dhaka Wasa. He is also known to have taken part in other civic protests and for expressing opinions critical of the government and state entities, including the police, for corruption and irregularities.

What Mizanur encountered since he was picked up from Bikrampur Plaza till his release are punishable offences under our own law, the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act, 2013. There are further stipulations by the Supreme Court in implementing the Act due to reported allegations of such violence, particularly in the context of custodial situations where law enforcement agencies seek to obtain confessional statements from the arrestees following arrest or detention. The UNCAT, too, in its final observation, recommended that the government should “[u]nambiguously affirm at the highest level… that law enforcement authorities must immediately cease engaging in the practice of unacknowledged detention.” The Supreme Court’s guidelines were issued in 2016, three years before the UNCAT’s recommendations.

We need an end to unacknowledged detention and custodial torture. And it should begin with an independent investigation into Mizanur’s unacknowledged detention. Without accountability of the perpetrators of such unlawful brutality and torture, they won’t end.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist and writes from London, UK. His Twitter handle is @ahmedka1