Indelible Imprints: The Genius from Khulna

This is the story of Qazi Azizul Haque, a boy from Khulna who ran away from home and ended up in Calcutta during the British rule, becoming a great scholar of mathematics who significantly contributed to the invention of a world-wide used method of fingerprint identification

Khan Bahadur Qazi Azizul Haque was born in 1872, in the village of Paigram Kasba, Phultala, in the Khulna district of Bengal, British India, now in Bangladesh. His parents died in a boat accident when Haque was a minor. Family lore has it that the sudden loss of parents, especially, the father, entailed great financial hardship on the family, leaving Haque’s older brother look after the family. Haque was a precocious child with an uncanny ability to solve numerical problems. His other passion was food – from all accounts he was a hearty eater. Since, the family was hard up, Haque was often scolded by his older brother to mend his eating habits. However, one day his brother returned home, hot and tired from work, to find that Haque besides eating his own share of the meal, had also consumed a substantial portion of his brother’s food. Enraged, he soundly thrashed him for his gluttony. Humiliated and heartbroken, Haque stealthily left the house, boarded a passing train and arrived in Calcutta and that is where the real story begins.

One can quite imagine the profound culture shock of a twelve-year-old, that too, from an obscure village in the backwaters of East Bengal, to suddenly find himself in the premier city of the subcontinent, Calcutta, then the capital of the British Raj. The year was 1884. And, Haque at a tender age, was a run-away from home, all alone in bustling Calcutta!

However, instead of becoming a street urchin or vagrant, Haque was a rare one with luck. Providence smiled upon him. Destiny had ordained fame and fortune for him in life. As the story goes, a lost, famished and weary Haque, was found sleeping outside the home of a wealthy, distinguished Bengali Babu, who took pity on him and employed him as an errand boy in his house. The kind gentleman was a Hindu. Such a magnanimous act of taking in a Muslim boy in a Hindu household was unheard of in those days, since the Hindu society then was highly conservative and insidiously caste ridden. But Haque’s benefactor was an enlightened soul.

Haque settled down in the large Calcutta house of his mentor doing odd chores. However, when the house tutor, a Pandit, would come by to teach the children of the house, Haque would eagerly squat on the floor nearby and take interest in the lessons. It so happened that pretty soon Haque was solving mathematical problems which the children of the house could not. An astonished house tutor then further grilled Haque and was surprised by his mathematical acumen and promptly reported the matter to the master of the house.

The kind Hindu gentleman further queried Haque, who at last told him the truth – that he was a runaway from home with some formal schooling in his village. The gentleman was convinced that Haque was a gifted boy. Then and there, he arranged proper schooling for the child. After that there was no looking back for Haque.

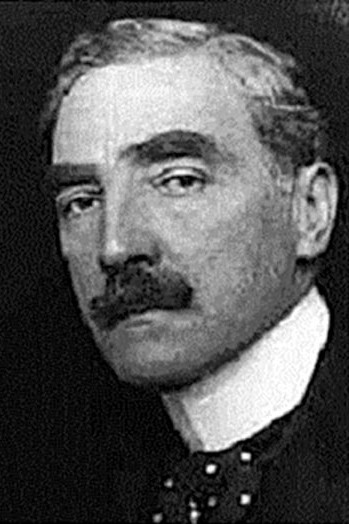

Finishing school with good results, Haque went on to attend the prestigious Presidency College in Calcutta where he excelled in mathematics and science. In 1892, Sir Edward Richard Henry (1850-1931), Inspector General of the Bengal Police, wrote to the principal of the Presidency college requesting him to recommend one of his students with a strong background in statistics, for a job under him in the police service. The college principal, already highly impressed with Haque, immediately recommended him, whereby, Haque was recruited by Sir Henry as a Police Sub-Inspector along with another young man, Hem Chandra Bose.

Both Haque and Bose were employed by Sir Henry to develop the, “Henry Classification System” of fingerprints. Haque, reportedly, provided the mathematical basis for the system, while Bose complemented it by devising a telegraphic code system for fingerprints. The research of Henry-Haque- Bose revolutionised criminology (criminal investigation and identification) and the successful application of the “Henry Classification System” of fingerprinting worldwide for a century (1899-1990s). In fact, the “Henry Classification System” also played a highly influential role in the development of the current biometric systems, that is, in the formation of today’s AFIS technology (Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System). When AFIS technology was first introduced, it was primarily envisioned to be used as a tool to expedite the manual searching of fingerprint records, eventually reducing matching time requirements from months to hours. At that time, most forensic hardcopy fingerprint files were sorted according to the “Henry Classification System”, and the first AFIS solutions attempted to emulate the Henry process. However, up until the mid-1990s, it was not unusual for a state or city worldwide to continue to maintain its physical file of Henry-sorted fingerprint cards, just in case a disaster occurred in the AFIS. As processing speeds, network capacities, and system reliability increased with the advancement of digital technology, it was no longer necessary for automated fingerprint matching to mirror what had once been a manual process.

Although, hand impressions and fingerprint characteristics have bedeviled mankind from time immemorial, serious studies of it started only from the mid-1600s onwards in Europe. However, the use of fingerprints as a means of identification did not occur until mid-19th century. In about 1859, Sir William James Herschel (1833-1917), ICS, discovered that fingerprints remain stable over time and are unique across individuals. As Chief Magistrate of the Hooghly district in Jungipur, India, in 1877, he was the first to institute the use of fingerprints as a means of identification, signing legal documents, and authenticating transactions. The fingerprint records collected at this time were used for one-to-one verification only, as a means in which records would be logically filed and searched.

In 1892, Sir Francis Galton (1822- 1911), a progressive English Victorian statistician, published his highly influential book, “Finger Prints” in which he described his classification system that include three main fingerprint patterns – loops, whorls and arches. In 1894, Sir Edward Richard Henry, Inspector-General of the Bengal police in India became interested in the use of fingerprints for the use of criminal investigation. At that time, the alternative to fingerprints was Bertillonage, also known as Anthropometry, developed by Alphonse Bertillon (1853-1914), a French police officer and biometrics researcher, in 1879. Anthropometry consisted of a meticulous anthropological method of measuring body parts for the use of identifying criminals. In 1892, the British Indian Police adopted Anthropometric measurements.

In January 1896, Sir Henry ordered the Bengal Police to collect prisoner’s fingerprints in addition to their anthropometric measurements. Expanding on Galton’s classification system, Sir Henry developed the Henry Classification System between the years 1896 and 1925. As mentioned earlier, he was primarily assisted in his endeavour by Azizul Haque who developed the mathematical formula to supplement Henry’s idea of sorting in 1024 pigeon holes based on fingerprint patterns. Sub-Inspector Hem Chandra Bose, another assistant of Sir Henry also helped in refining the system by helping in devising the telegraphic method for the system. On Sir Henry’s recommendation both his assistants were to receive recognition for their valued contribution from the British government, years later.

The Henry Classification System was to find worldwide acceptance in 1899. In 1897 a commission was established to compare Anthropometry to the Henry Classification System. As the results were overwhelmingly in favour of fingerprints, fingerprinting was introduced in British India by the Viceroy, and in 1900 replaced Anthropometry.

Meanwhile, once professionally established, Haque visited his older brother in his village home in Khulna from whom he had been estranged for many years after he had run away from home. Haque’s brother, who had given up hope of ever seeing him, was overjoyed to see him again. Furthermore, he was overwhelmed to learn of Haque’s academic and professional achievements in life. He promptly arranged Haque’s marriage to their cousin sister.

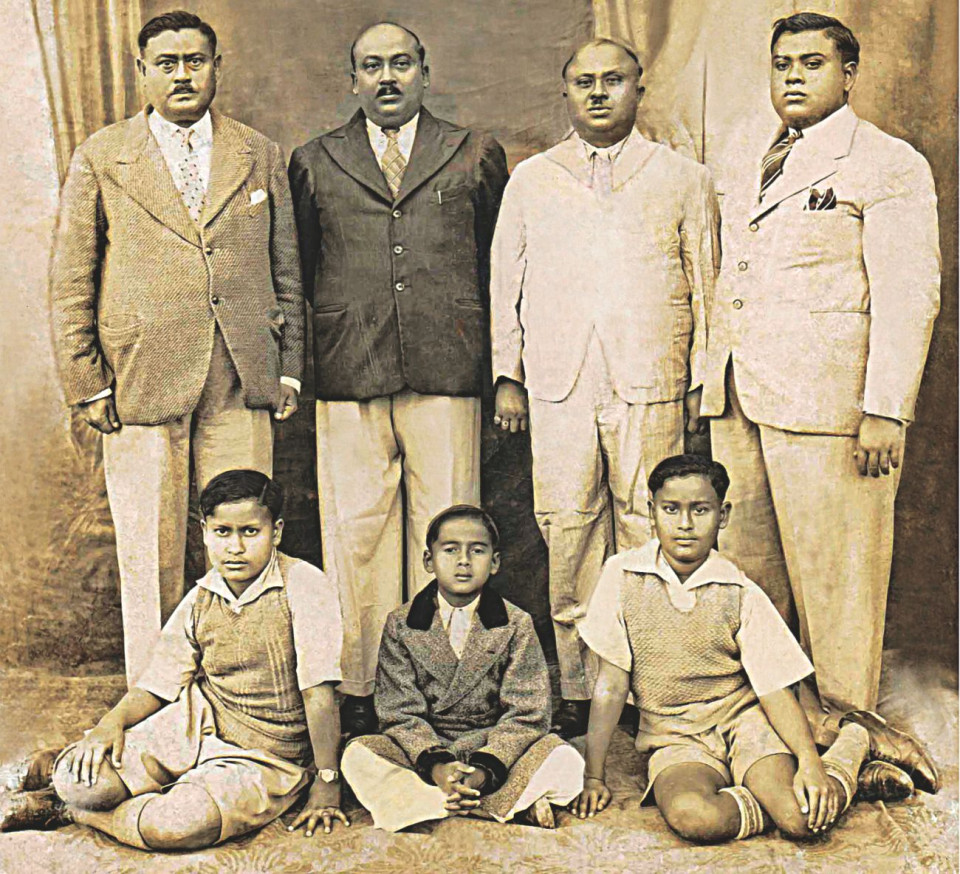

As a distinguished police officer, Haque, subsequently opted to join the Bihar Police Service when Bihar was separated from the Bengal Presidency in 1912. Upon his retirement from service, he settled in Motihari, Bihar, where he died in 1935 and lies buried. He had eight surviving children. His wife, and the children with their families migrated to Pakistan after the partition of British India in 1947, and presently their descendants are settled in Bangladesh, Pakistan, United Kingdom, Australia and North America (USA and Canada).

Historians, researchers and experts on the subject of fingerprinting, both Indian and Western, have over the years unanimously acknowledged the singular role of Azizul Haque as the man who contributed the maximum in devising and perfecting the Henry Classification of fingerprints. For his exceptional contribution Haque received the title of Khan Sahib in 1913, and that of Khan Bahadur in 1924 from the British government along with a Jaigir (feudal land grant) in Motihari, Bihar, India. Similarly, Bose also received the decoration of Rai Sahib and Rai Bahadur – the Hindu counterparts of the titles bestowed upon Haque. Furthermore, both received an honorarium of 5,000 rupees each for their outstanding contributions to the establishment of fingerprinting classification. Perhaps, the most befitting tribute to the genius of Haque, finally came from his former boss, Sir Edward Richard Henry, who had earlier taken most of the credit for himself, and who at last publicly acknowledged by saying that, “Khan Bahadur Azizul Haque is the man mainly responsible for the new worldwide fingerprint system of identification.”

The writer is Founder, Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies

Source: Daily Star