Chowdhury Mueen-Uddin, convicted of war crimes in Bangladesh, appeals against decision to strike down libel case involving UK government report stating that he was “guilty of crimes against humanity”.

The report was referring back to his conviction by the Bangladeshi tribunal for his alleged involvement in the killing of 18 intellectuals at the very end of Bangladesh’s nine-month long liberation war, which had pitted the Pakistani military against Bengali freedom fighters.

Mueen-Uddin was found by the Bangladesh court to have been a leader of the Al Badr militia, comprising members of the student wing of the fundamentalist Jamaat-e-Islami (JEI), which assisted the Pakistani military during the war, and was responsible for these killings. The murders of the 18 people, one of the most notorious massacres that took place during the war, are commemorated as Martyred Intellectual Day in Bangladesh every year on December 14th. Following his conviction, the tribunal sentenced Mueen-Uddin to death.

However, the former East London Mosque vice-chairman has argued that the trial in Bangladesh was “grossly unfair” and that he is completely innocent of the allegations. He has previously said that he “was a journalist at the time, and yes, I supported the unity of Pakistan. However, supporting the unity of a sovereign nation is one thing, getting involved in crimes is not what I have taken part in any way, shape or form.” His lawyers argue that the Home Office report, which “added the imprimatur of the UK government to the conviction” libelled him as it referred to his conviction without explaining that the tribunal was beset with procedural irregularities and unfairness, and could not in reality appeal the finding without putting himself in danger of execution.

The International Crimes Tribunal, set up by the Awami League government in 2009, has convicted over hundred people, most of them members of the JEI or its student wing during the war — with almost half receiving a death sentence, and nine people so far having been executed. However, despite significant popular support within Bangladesh, many international human rights organisations have criticised it for inadequate fair trial standards and its politicisation. Its trials have from time to time been beset with scandal and controversy.

After Mueen-Uddin’s lawyers issued proceedings over the report, the British Home Secretary applied to the High Court to strike out the libel case as “an abuse of process”. One of the Government lawyers key arguments is that if the libel claim were to proceed, it would in effect involve re-litigating whether Mueen-Uddin was guilty of the murders of the 18 intellectuals. Referring to judicial precedents, the lawyers argued, it would be an “abuse to seek to relitigate in subsequent civil proceedings whether a person has been rightly convicted in a criminal court.”

Both the High Court in November 2021 and subsequently the Appeal Court in July 2022 (in a majority two to one decision), accepted the government’s arguments and struck out the case. However, with one of the three court of appeal judges arguing in favour of Mueen-Uddin – that the British courts should not “place any reliance on the decision of the ICT” because of the unfairness of the proceedings – the Supreme Court agreed on February 1st, to hear Mueen-Uddin’s appeal. No appeal date has yet been set.

The Supreme Court hearing is likely to make difficult listening for the Bangladesh government, as not even the UK government is arguing that the Tribunal was fair — only that UK courts should not be used as a “collateral attack” on a finding of guilt by a criminal conviction, even when that conviction involves a foreign court which has unfair practices. Moreover, if the Supreme Court decides in favour of Mueen-Uddin, in effect supporting the decision of the minority judge at the Appeals Court, the judgement could include significant criticism of the tribunal.

A victory for Mueen-Uddin could also result, assuming the parties did not settle the case, in a fascinating libel trial in which his role in 1971 would again be considered in a judicial setting — but this time in the British courts.

Government attempt to “strike out” the case

On October 7th 2019 the Commission for Countering Extremism published a report setting out its “research-based view on contemporary extremism”, including case studies and an assessment of the government’s 2015 Counter-Extremism Strategy. One had to be quite a close reader of the 144 page report to read the footnote which referred to Chowdhury Mueen-Uddin and the claim that he was “found guilty of crimes against humanity following a trial in absentia”. However, Mueen-Uddin said that he had been contacted by numerous colleagues and associates who had read the report and the allegations about him contained within it.

Two months later, on December 12th 2019, Mueen-Uddin’s lawyers sent a letter of claim to the Home Office, following which on March 20th 2020, the report’s authors edited the online version of the report to remove the footnote that referred to him. Two months later, the lawyers served libel proceedings against the Home Secretary.

The meaning of the relevant part of the report and footnote was determined by Justice Tipples on February 16th 2021, ruling that the “natural and ordinary meaning” of these words in the footnote was that Mueen-Uddin “was one of those responsible for war crimes committed during a War of Independence in 1971; and had committed crimes against humanity during a 1971 War of Independence in South Asia”.

With proceedings initiated, the Home Secretary applied to the High Court to strike out the case as “an abuse of process” of the court. UK Government lawyers said that Mueen-Uddin may have many criticisms of the fairness of the trial, “but the forum to ventilate these complaints was the trial itself or an appeal against conviction or sentence; not a subsequent civil claim.” They added that, “[T]he present proceedings would be an abuse even if all that the claimant said about the ICT proceedings [that it was not fair and impartial] was correct.”

In November 2021, the High Court judge, Sir Andrew Nicol, ruled in favour of the Home Secretary: “The inevitable consequence of the claim is that the correctness of the ICT’s conclusion that the claimant was guilty of war crimes will be in issue … [and] the courts are particularly vigilant to guard against a collateral attack on a finding of guilt by a criminal conviction.”

The judge went on to say that, “The conclusion to which I have come implies nothing about the merits of the claimant’s claim that the proceedings in Bangladesh were grossly unfair to him.”

The Court of Appeal

Mueen-Uddin lawyers appealed the High Court decision, arguing that the judge did not take into account the fact that “he could not attend hearing of the charges against him in Bangladesh without risking death and in those circumstances the suggestion that he could and should have availed himself of an appeal is entirely unreal.” They also argued that there is “no impact on reputation of British justice”, if a British court comes to a different decision from a foreign court operating in a different system of justice and applying different rules.

But Lord Justice Dingemans, in the leading judgement of the Court of Appeal, upheld the earlier court decision ruling that “in the very particular circumstances of this case” it would be an “abuse of process” to allow the legal action to proceed further.

In his judgement, Dingemans agreed with the High Court that a key factor was “the fact that Mr Mueen-Uddin has been convicted of the murder of the intellectuals before the International Crimes Tribunal in Bangladesh.” The conviction in Bangladesh, he said, remained significant despite concerns over “the rules of evidence applied by the tribunal,” and that Mueen-Uddin could not appear in person before the tribunal because of “the risk of a death sentence” and “the international criticism of the procedures of the tribunal.”

Dingemans said that another factor behind his ruling concerned whether Mueen-Uddin could show that the publication of this home office report had itself caused serious harm to his reputation. The judge held that since the end of December 1971, Mueen-Uddin had already a reputation, as reported in Bangladesh and international media, of having been “involved in the murder of the intellectuals”. He pointed particularly to the broadcast in 1995 of a Channel 4 Dispatches documentary, “The War Crimes Files”, in which Mueen-Uddin was accused of being involved in the murder of the intellectuals. “Such a programme generated substantial publicity and although Mr Mueen-Uddin commenced proceedings to vindicate his reputation, he did not pursue them,” the judge said.

The Court of Appeal judge said that a further factor behind his decision is that it would have been “impossible” for the Home Secretary “to obtain a fair hearing” to defend himself against the claim of libel because of “the length of time since the murder of the intellectuals in December 1971, which was over 50 years ago”, pointing out that many of the relevant witnesses were dead.

“If the proceedings continue there will be the wretched spectacle of a judge attempting to do his or her honest best to determine whether the allegations against Mr Mueen-Uddin are true or substantially true without much live evidence. Whatever the judge concluded would not lead to a vindication of Mr Mueen-Uddin’s reputation, and this is because those who do not accept the result will point to the absence of relevant witnesses and evidence. A proper time to vindicate Mr Mueen-Uddin’s reputation would have been at the time of the Channel 4 proceedings,” he noted.

Minority judgement

Lord Justice Dingeman’s judgement was supported by Dame Victoria Sharp, but there was a minority judgement given by Lord Justice Phillips. He argued that while it was right to be vigilant to guard against a collateral attack on a finding of guilt by a criminal conviction, even where it involved a foreign court, “the courts of this country must necessarily give careful scrutiny to any question raised as to whether an accused had a full opportunity to defend himself in the foreign court.”

After detailing the procedures of the ICT, he said: “In my judgement it is clear beyond contradiction, on the evidence before the judge, that the appellant did not have a full opportunity to defend himself at the ICT, or indeed any opportunity at all. He was wrongfully tried in his absence, without formal notification of the proceedings or receipt of prosecution materials, in circumstances where he cannot reasonably have been expected to attend (given the likely imposition of the death penalty). Further, the proceedings fell far short of the standards of fairness recognised in these courts and internationally, several crucial issues being determined on the basis of multiple hearsay, consisting of or corroborated by newspaper reports of some antiquity.”

He also said that it was unclear how Mueen-Uddin “could have advanced an appeal” against conviction, but even if that was available, the judge said he could not see how it could “cure a process as inherently unfair and unjust as that adopted by the ICT, where the legitimacy of the conviction is seriously in doubt on any international standard of fairness.”

He went on to add that: “I find it surprising that these courts (and, for that matter, the government), would place any reliance on the decision of the ICT in the appellant’s case, let alone regard it as abusive for the appellant to mount a claim inconsistent with that decision.”

Lord Justice Phillips also pointed out that the footnote in the Home Office report represented “An unequivocal and unqualified assertion of the appellant’s guilt” made by the UK government, “In my judgement it is not difficult to see the damage the government’s endorsement of his conviction would do to the appellant’s reputation in this country and in his community in particular: it undermined his plausible denials of the crimes and ‘officially’ recognised him as being guilty notwithstanding those denials.”

Philips concluded: “I would add that, having been denied a fair trial in Bangladesh in 2013, it would be unfortunate if the appellant was now prevented from having access to the courts of this jurisdiction, at least in part because of his conviction by the ICT.”

Chowdhury Mueen-Uddin

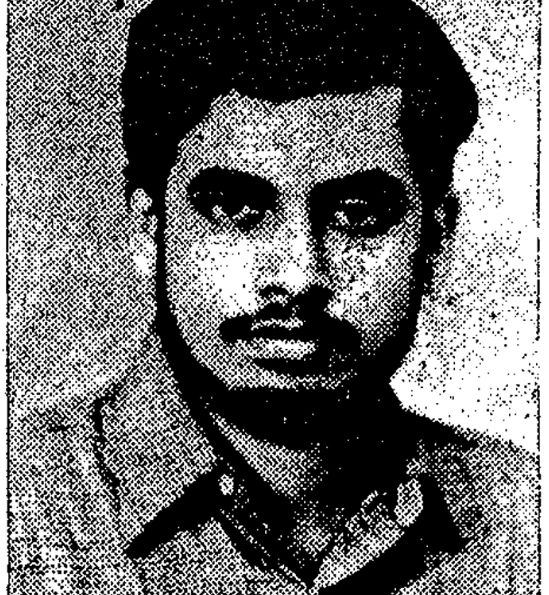

Mueen-Uddin’s name first came to public attention in a news item in Bangladesh’s Observer newspaper, titled, “Absconding Al Badr gangster” which contained his picture. “Chowdhury Mainuddin (sic), a member of the banned fanatic Jamaat Islam party, has been described as the ‘operation in charge’ of the killing of intellectuals in Dacca by Abdul Khaleque, a captured right leader of the Al Badr and office-bearer of the Jamaat-e-Islam,” it stated.

A few days later, the New York Times published an article headlined, “A journalist is linked to murder of Bengalis”, which referred to him. Subsequently, Mueen-Uddin’s name was mentioned in a number of books investigating alleged crimes during the 1971 war.

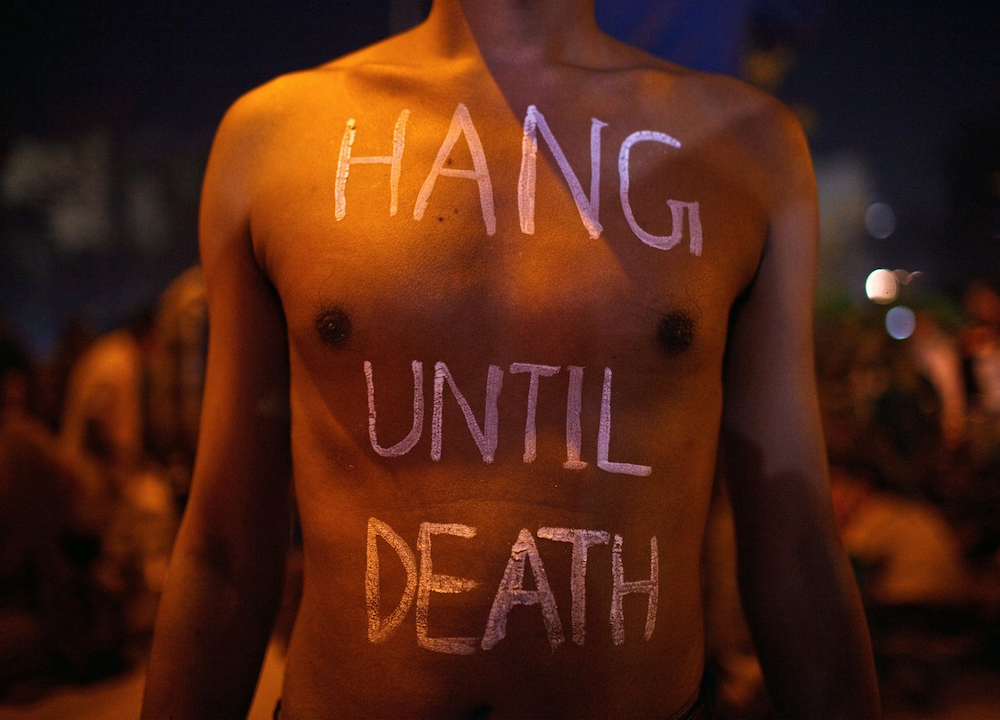

However, his name came to wider attention in 1995, when Channel Four Dispatches broadcast a documentary, The War Crimes Files, which investigated allegations that three men — one of whom was Chowdhury Mueen-Uddin — committed war crimes during the 1971 war. The documentary contained testimony from:

— The wife of university professor, Moffazel Haider Chowdhury, who said that she recognised the face of Mueen-Uddin among the men who abducted him;

— The wife of the journalist Serajuddin Hossain, who witnessed Mueen-Uddin as amon the men who abducted her husband;

— Two men who after the war identified Mueen-Uddin as one of the men who came to the house of Ataus Samad to try and abduct him;

— The journalist Atiqur Rahman worked with Mueen-Uddin in the newspaper “Purbodesh”. When asked by Mueen-Uddin about his address, he gave a fake number, and this same fake number was subsequently found in a list of men whom Al Badr tried to abduct.

Mueen-Uddin denies any involvement in these crimes.

As set out in the Court of Appeal judgement, Mueen-Uddin acknowledged he had been a member of the student wing of the JEI, but said that he has had resigned his membership in June 1971 following the Pakistan military’s military crackdown a few months earlier and the failure of the student wing to condemn it. “Mr Mueen-Uddin said he was opposed to Bangladesh separating from Pakistan, but he did not take part in any violence,” the court stated.

Mueen-Uddin said that he left Bangladesh on December 28th 1971, within weeks of the end of the war after “he became aware that allegations had been made by an individual that he was a member of Al-Badar and responsible for the abduction and killing of the intellectuals”, that “he did not know why he had been accused of the murder of the intellectuals” and left the country as he “did not feel safe in Bangladesh”.

Mueen-Uddin goes on to say that he travelled via India and Nepal and arrived in the UK in June 1973. “He said he reported to the Home Office that allegations had been made against him,” the judgement reads. “He said he was interviewed by the Home Office, but nothing was found to support the allegations made against him and he was encouraged to apply for British citizenship. Since 1973 Mr Mueen-Uddin has been living in London as an active and engaged member of British society. He visited Bangladesh on a number of occasions from 1982. He became a British citizen in 1984.”

After the Channel Four film was broadcast, Mueen-Uddin commenced proceedings against the broadcaster, but says that this was not pursued. “I did not have the financial resources at the time to pursue the case to trial, which therefore ended without either side paying the other’s costs,” he stated in his witness statement for this new libel action.●

David Bergman (@TheDavidBergman) — a journalist based in Britain — is Editor, English of Netra News. He was part of the team that made the Channel Four, Dispatches, and he ran the Bangladesh War Crimes Trial Blog.