The IWT is a 56-year-old accord that governs how India and Pakistan manage the vast Indus River Basin’s rivers and tributaries.

Early on the morning of September 29, according to India’s Defence Ministry and military, Indian forces staged a “surgical strike” in Pakistan-administered Kashmir that targeted seven terrorist camps and killed multiple militants. Pakistan angrily denied that the daring raid took place, though it did state that two of its soldiers were killed in clashes with Indian troops along their disputed border. New Delhi’s announcement of its strike plunged already tense India-Pakistan relations into deep crisis. It came 13 days after militants identified by India as members of the Pakistani terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed killed 18 soldiers on a military base in the town of Uri, in India-administered Kashmir.

Amid all the shrill rhetoric and sabre rattling emanating from India and Pakistan in recent days, including India’s home minister branding Pakistan a “terrorist state” and Pakistan’s defence minister threatening to wage nuclear war on India, one subtle threat issued by India may have sounded relatively innocuous to the casual listener.

On September 22, India’s Foreign Ministry spokesman suggested, cryptically, that New Delhi could revoke the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). “For any such treaty to work,” warned Vikas Swarup, when asked if India would cancel the agreement, “it is important for mutual trust and cooperation. It cannot be a one-sided affair.”

Indus Waters Treaty (IWT)

The IWT is a 56-year-old accord that governs how India and Pakistan manage the vast Indus River Basin’s rivers and tributaries. After David Lilienthal, a former chairman of the Tennessee Valley Authority, visited the region in 1951, he was prompted to write an article in Collier’s magazine, in which he argued that a trans-boundary water accord between India and Pakistan would help ease some of the hostility from the partition, particularly because the rivers of the Indus Basin flow through Kashmir. His idea gained traction and also the support of the World Bank. The bank mediated several years of difficult bilateral negotiations before the parties concluded a deal in 1960. US President Dwight Eisenhower described it as a “bright spot” in a “very depressing world picture.” The IWT has survived, with few challenges, to the present day.

On September 26, India’s government met to review the treaty but reportedly decided that it would not revoke the agreement for now. New Delhi left open the possibility of revisiting the issue at a later date. Ominously, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi told top officials present at the treaty review meeting that “blood and water cannot flow together.” Additionally, the government suspended, with immediate effect, meetings between the Indus commissioners of both countries’ high-level sessions that ordinarily take place twice a year to manage the IWT and to address any disagreements that may arise from it.

These developments have spooked Pakistan severely. Sartaj Aziz, the foreign affairs advisor to Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, said revoking the IWT could be perceived as an “act of war,” and he hinted that Pakistan might seek assistance from the UN or International Court of Justice.

If India were to annul the IWT, the consequences might well be humanitarian devastation in what is already one of the world’s most water-starved countries, an outcome far more harmful and far-reaching than the effects of limited war. Unlike other punitive steps that India could consider taking against its neighbour, including the strikes against Pakistani militants that India claimed to have carried out on September 29 cancelling the IWT could have direct, dramatic, and deleterious effects on ordinary Pakistanis.

Pakistan’s concern on IWT

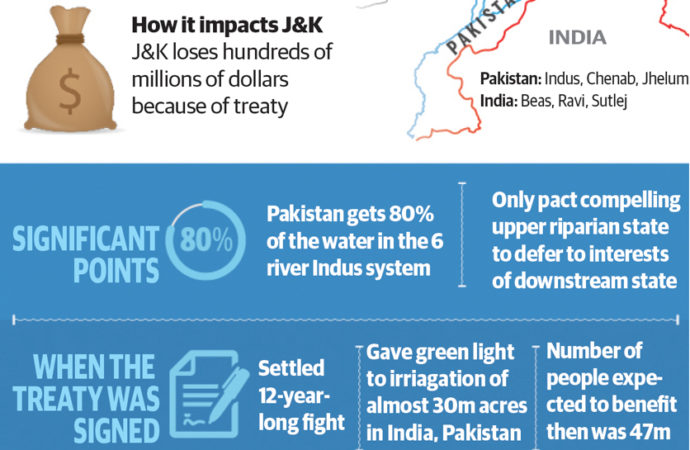

The IWT is a very good deal for Pakistan. Although its provisions allocate three rivers each to Pakistan and India, Pakistan is given control of the Indus Basin’s three large western rivers- the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab, which account for 80% of the water in the entire basin. Since water from the Indus Basin flows downstream from India to Pakistan, revoking the IWT would allow India to take control of and if it created enough storage space through the construction of large dams, stop altogether the flow of those three rivers into Pakistan. To be sure, India would need several years to build the requisite dams, reservoirs, and other infrastructure to generate enough storage to prevent water from flowing downstream to Pakistan. But pulling out of the IWT is the first step in giving India carte blanch to start pursuing that objective.

Pakistan is deeply dependent on those three western rivers and particularly the Indus. In some areas of the country, including all of Sindh province, the Indus is the sole source of water for irrigation and human consumption. If Pakistan’s access to water from the Indus Basin were cut off or merely reduced, the implications for the country’s water security could be catastrophic. For this reason, using water as a weapon could inflict more damage on Pakistan than some forms of warfare.

Pakistan is one of the most water-stressed countries in the world, with a per capita annual water availability of roughly 35,300 cubic feet, the scarcity threshold. This is all the more alarming given that Pakistan’s water intensity rate, a measure of cubic meters used per unit of GDP is the world’s highest. In other words, Pakistan’s economy is the most water-intensive in the world, and yet it has dangerously low levels of water to work with.

Pakistan depends on the Indus river, which starts in Tibet and runs through Ladakh on the Indian side of Jammu and Kashmir, before reaching Pakistan Collected

How does it affect Jammu and Kashmir?

Jammu and Kashmir too has not been able to harness the full potential of the treaty. In 2007, the Union Water Ministry had estimated Jammu and Kashmir can increase its Irrigated Cropped Area (ICA) by 4,25,000 acres. But today, Out of 6,00,000 Hectares of cultivated land in Jammu and Kashmir only 1,50,000 Hectares is under irrigation. This has also affected hydropower generation. Current estimates suggests there is a possibility of harnessing more than 20,000MW but today there is only an estimated 2,500MV being harnessed.

It is revealed from the above analysis that the actual power potential of Jhelum, Chenab, Indus and Ravi are 3,560MW, 10,360MW, 2,060MW and 50MW respectively. Currently, the harnessed potential of these river basins are 750.1MWs, 1563.8MWs, 13.3MWs, and 129MWs respectively.

Possible water war?

There are other compelling reasons for India not to cancel the IWT, all of which go beyond the hardships the decision could bring to a country where at least 40m people already lack access to safe drinking water.

First, revoking the treaty, an international accord mediated by the World Bank and widely regarded as a success story of trans-boundary water management would generate intense international opposition. The IWT will bring global condemnation, and the moral high ground, which India enjoys vis-a-vis Pakistan in the post-Uri period will be lost. Also, the World Bank would likely throw its support behind any international legal action taken by Pakistan against India.

Second, if India decided to maximise pressure on Pakistan by cutting off or reducing river flows to its downstream neighbour, this would bottle up large volumes of water in northern India, a dangerous move that according to water experts could cause significant flooding in major cities in Kashmir and in Punjab state

Third, if India ditches the IWT, then it could set a dangerous precedent and give some ideas to Pakistan’s ally, China. Beijing has never signed on to any trans-boundary water management accord, and New Delhi constantly worries about its upstream rival building dozens of dams that cut off river flows into India. The Chinese, perhaps using as a pretext recent Indian defensive upgrades in the state of Arunachal Pradesh, which borders China and is claimed by Beijing, could well decide to take a page out of India’s book and slow the flow of the mighty Brahmaputra River.

What this all means is that India’s cancellation of the IWT would not produce New Delhi’s hoped-for result- Pakistani crackdowns on anti-India terrorists. On the contrary, Pakistan might tighten its embrace of such groups. The mere act of cancelling the IWT, even if India declines to take steps to reduce water flows to Pakistan would be treated in Islamabad as a major provocation, with fears that water cutoffs could follow, and thereby spawn retaliations.

source; dhaka tribune