A Mike Flynn-Approved Hate Group Is Teaching Cops to Track Muslims

A Mike Flynn-Approved Hate Group Is Teaching Cops to Track Muslims

How a former FBI agent delivered a tool for tracking Muslims into the Trumpian mainstream.

The Centennial Institute at Colorado Christian University is a conservative think tank that offers limited classes and is not, as the name would imply, an actual university. Yet on a September afternoon in 2014, John Guandolo, dressed in a slightly rumpled grey suit, looked like any other college adjunct standing in front of PowerPoint slides. His lecture was titled, “Civilization Jihad in America — Are You Prepared?,” a more ominous theme than Guandolo’s tone.

A former FBI agent, John Guandolo has been described as a “Paul Revere,” sounding the clarion call for war in the homeland. Though he began touring through his company “Understanding The Threat” back in 2010, his theories are now having a resurgence within mainstream government, thanks to Donald Trump. Guandolo, for example, was the main author of legislation proposed last week, sponsored by Ted Cruz, to make the Muslim Brotherhood an official terrorist group.

“If you want to boil it down to what the greatest problem is…I believe it’s us,” Guandolo said back in September 2014, speaking with an earnest lilt. By this, he was referring to his followers — the white, Christian majority — who Guandolo believes need to reinvent society to target those who don’t fit. In his view, everyone who isn’t Christian poses a threat—especially Muslims.

Guandolo now keeps his talks under wraps, but they are legion across the country. They take place in police union halls, conference centers, colleges, and church basements. They are sponsored by private funders, unions, and local police departments where he offers trainings on “the Islamic threat.” They tend to occur in places where local officials appear more receptive to his message — namely Colorado, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, the latter being where his company is based. Law enforcement in Arizona paid Guandolo $11,000, not including the cost of catering and a hefty supply of his books, to give a lecture eligible for continuing education credits.

Yet Guandolo offers more than just lectures. At these talks and on his website, Guandolo promotes a tool of his own creation, designed to support local law enforcement in their quest to conquer what he calls “homegrown terrorism.” The Thin Blue Line Project is a website intended to assist federal and local law enforcement with finding and targeting radicalized Muslims. It has no official government affiliation, but according to a press release, the website is being used by members of the NYPD, the FBI, Homeland Security, ICE, and Border Patrol. The Thin Blue Line Project offers training videos, tips on catching terrorists, a live stream of news, a message board, and, most importantly, a national map that geolocates Muslim targets. The locations are benign: Muslim student associations; mosques; offices of the Council On American-Islamic Relations. But, in Guandolo’s words, it’s a way to “locate these jihadis.”

The site urges police departments to take the “political correctness out of counter terrorism training,” lifting rhetoric almost directly from the current administration. It also borrows the popular police terms used to denote eternal loyalty, and morphs them into a hard-line approach of confronting Muslims.

Guandolo designed the website in collaboration with ACT for America, a group the Southern Poverty Law Center has classified an anti-Islamic hate group. It counts recently appointed National Security Advisor Michael Flynn as a member of its board. The group has actively promoted the site. In a September 2015 speech at the ACT national conference, Brigitte Gabriel, the group’s president and founder, bragged that the website earned subscribers from 11 government agencies. “We network to get all across the nation bypassing our government,” she said. “We can do what we do to train first responders: training that they are not getting from the government even though they should.”

Guandolo used to represent an extreme branch of law enforcement—one that sat far enough from the mainstream power structure to spread its ideology. But now, under the Trump administration, Guandolo represents the new anti-Islamic guard, along with Flynn, who has spoken at several local ACT conferences about the supposed dangers of Islam. And, like Guandolo, Flynn insists that Islam isn’t a “real” religion and therefore isn’t protected under the First Amendment.

On that day in the fall of 2014 at Colorado Christian University, Guandolo laughed about being called an Islamaphobe. Yet Guandolo and Flynn’s teachings, ideas that are enforced by ACT, are becoming entrenched in Washington’s power structure—namely, the notion that all of Islam, not just ISIS or Al Queda or other so-called radical movements, wants to threaten the American way of life. That Islam is a violent religion, which makes every Muslim susceptible to radicalization. That every Muslim is a potential danger. In other words, that the enemy is next door.

The Thin Blue Line Project uses the internet and modern map locator technology to grant the patina of law enforcement to a vigilante mission. If Guandolo’s concern is about “Sharia Creep,” then his outsized and undue influence on the Trump administration is another kind of creep altogether.

The Thin Blue Line Project begins with a trailer. In the introductory video, Arabic chanting sounds over pictures of bearded men strapped with AK-47s and wearing desert camo and head scarves. A voice asks a rhetorical question: “What if everything you were ever told…about the threat of radical Islam was wrong?” It looks like something from a Breibart-produced jihadist fever dream or the introductory sequence of Homeland.

Inside the site—which is password protected and only accessible by law enforcement—much of the training focuses on stereotypes and generalizations. There are claims that law enforcement should watch for young boys, whom the site falsely says are used in Muslim households as sex objects. There are training videos to show law enforcement how to “spot” terrorists through racial profiling — suggestions include trolling someone’s social media, noting accents, and looking for Muslim student association pamphlets. The site makes it easy for state and local agencies to follow the federal government in adopting anti-Muslim policies. As Guandolo told Tomi Lahren in November on Facebook Live in a video with over a million views, in his view, only local and federal action will extinguish the threat of Muslims in America.

At the heart of the Thin Blue Line Project is a “Radicalization Locator,” a Yelp-like feature that allows users to see at a glance all potential “targets” for law enforcement by entering parameters such as state or zip code. The sites, however, appear random—linked only by the fact that they are affiliated with Muslims. Using geolocation, the locator also features places that have seen police activity, such as a personal home in Brooklyn that was raided by police. (The address is visible.) The maps include the offices of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), Muslim Student Associations, and the meeting place of the Muslim American Society. Other “hot spots” are the home addresses for the directors of CAIR or Islamic associations. One named target is Suhail Khan, a political activist who was a senior political appointee in the Bush administration. Other individuals include an art history professor with a PhD in Islamic Studies, an Islamic counsel spokesperson, a college-aged girl who is already spending time in prison for trying to travel to Syria, and a cleric.

It’s not clear what law enforcement purpose these targets serve. But such target setting is a common tactic of Guandolo’s: In 2011, for example, he said in a training seminar that a Jordanian professor (who became an American citizen) was linked to jihadist organizations. The professor lost his job even though none of these connections were proven. The Thin Blue Line Project just makes Guandolo’s tasks more efficient by giving others the power to terrorize everyday civilians.

In my quest to understand the impact of the Thin Blue Line project, I contacted numerous agencies, including the sheriff’s departments for Culpepper County, Virginia, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Pima County, Arizona—all places where Guandolo has held trainings. Neither ACT nor Gabriel, its president, replied to repeated requests for comment. When I asked Guandolo for an interview, he replied, via email: “I am curious what Islamic Law you have read in preparation for your article and what research you have done on what Muslims teach their children in mosques across Europe and the United States.” He also denied his role in maintaining the site, writing, “I simply helped [ACT] put it together.” Yet his face appears on the Thin Blue Line Project itself, with an advertisement for his company. The Thin Blue Line Project appears on his website as a suggested source.

“I am curious what Islamic Law you have read in preparation for your article and what research you have done on what Muslims teach their children in mosques across Europe and the United States.”

When I asked to attend a recent training in Phoenix, Guandolo replied it was for “law enforcement personnel only,” although he does give the occasional public lecture, often over Facebook Live, Skype, or in a town hall setting (deemed a “national security briefing”). Just this month, “Understanding The Threat” began offering DVD versions of his talk for less than $15, condensed for a non-law enforcement audience.

Despite the veil of secrecy, many of Guandolo’s lectures and source materials are easily found online and offer insight into his views on law enforcement. His own Slideshare page focuses on conspiracy theories: that the head of the CIA is a “secret Muslim,” that mainstream organizations like CAIR and the Muslim American Society are funneling money to terrorist organizations like Hamas, and that all Muslims participate in the honor killings and genital mutilation that exists in only the most extreme version of Sharia law. (Guandolo says in his defense that he is just using “the primary sources used by the most authoritative schools of Islamic jurisprudence and textbooks used in Islamic schools in the US, Europe, Africa etc.”) He’s also advanced arguments that terrorists are coming from Mexico and are infiltrating the refugee programs—falsehoods that have trickled upwards to Donald Trump, as evidenced by his executive order last week.

The Southern Poverty Law Center points out that these tactics — publishing specific locations and encouraging vigilante-style justice — are the same ones used by other extreme right-wing groups. “The Thin Blue Line Project is taking a page from the playbook of oft-used tactics by extremists on the radical right, most notably by white supremacists and anti-abortion extremists, by publishing names and addresses of adversaries,” says Heidi Beirich, the director of SPLC’s Intelligence Project. When I called CAIR to ask about the website, a public relations representative asked, “What else is new?”, adding that anything ACT was involved with was bound to be anti-Muslim in every possible way.

Though it’s unclear whether law enforcement is actually using the site, it’s evident that one of the roles of the Thin Blue Line Project, and technology like it, is to legitimize a regime of fear and surveillance. The SPLC has noted an uptick in hate crimes against Muslims in the aftermath of the 2016 election, and there have been recent reports of people targeting mosques and other representative places for defacement and injury. Just this past Sunday, a Canadian man walked into a mosque with a gun and killed six people. FBI statistics have shown that hate crimes against Muslims are at their highest since post-9/11, noting a 78 percent increase. The Thin Blue Line Project takes this all another step forward by integrating technology, making the same information accessible to anyone who can receive a password from ACT.

Far from an isolated project, the Thin Blue Line Project is part of a larger campaign to create a radical form of policing. It’s based on a notion that “political correctness” has hampered our ability to enforce law, something that General Michael Flynn has touted as he rises to power as the national security advisor of the Trump administration.

Speaking at ACT’s 2016 national conference last year, Flynn famously called Islam a “cancer.” Just recently, Gabriel sent out an email touting Flynn’s appointment and announcing optimism for ACT under Trump’s administration. “As has been noted by a variety of national news outlets, ACT for America has a direct line to Donald Trump, and has played a fundamental role in shaping his views and suggested policies with respect to radical Islam,” she wrote.

“Political correctness” is a concept that Gabriel and ACT have long used as a battle cry to legitimize falsehoods and prejudice against Muslims and related advocacy groups. ACT’s website boasts 400,000 members in nearly 1,000 local chapters, and an annual budget of $1 million, although experts have suggested that this number is inflated. Though ACT touts itself as the “NRA of national security,” its policies are undeniably anti-Muslim, have little basis in fact, and are based on a conservative agenda. For example, one arm of ACT is Truth in Texas Textbooks, which quibbles with textbooks about the facts of evolution and climate change.

“The Thin Blue Line Project is taking a page from the playbook of oft-used tactics by extremists on the radical right, most notably by white supremacists and anti-abortion extremists, by publishing names and addresses of adversaries.”

The risk, of course, is that post-fact organizations like ACT might become interchangeable with legitimate research. Dr. John Esposito, who is the project director of Georgetown University’s Bridge Initiative, believes that ACT and its related initiatives are “very, very dangerous in terms of the safety and security of many Americans,” and points out that they rely on people billed as experts who have little to no actual training.

There’s already precedent for ACT’s rhetoric to filter upwards toward the public consciousness and affect national security policy. (The FBI and other groups within the Department of Defense have defended using anti-Muslim rhetoric in their training materials.) But more than that, the danger of the Thin Blue Line Project is that it adopts user-friendly technology, in service of the extreme. As Guandolo has written, “understand that LOCAL POLICE are the tip of the spear, and this problem will be solved by citizens at the LOCAL level.” In other words, the point of the Thin Blue Line Project is to bring hateful rhetoric to state and local governments, who also have increasing power to survey and prosecute individuals.

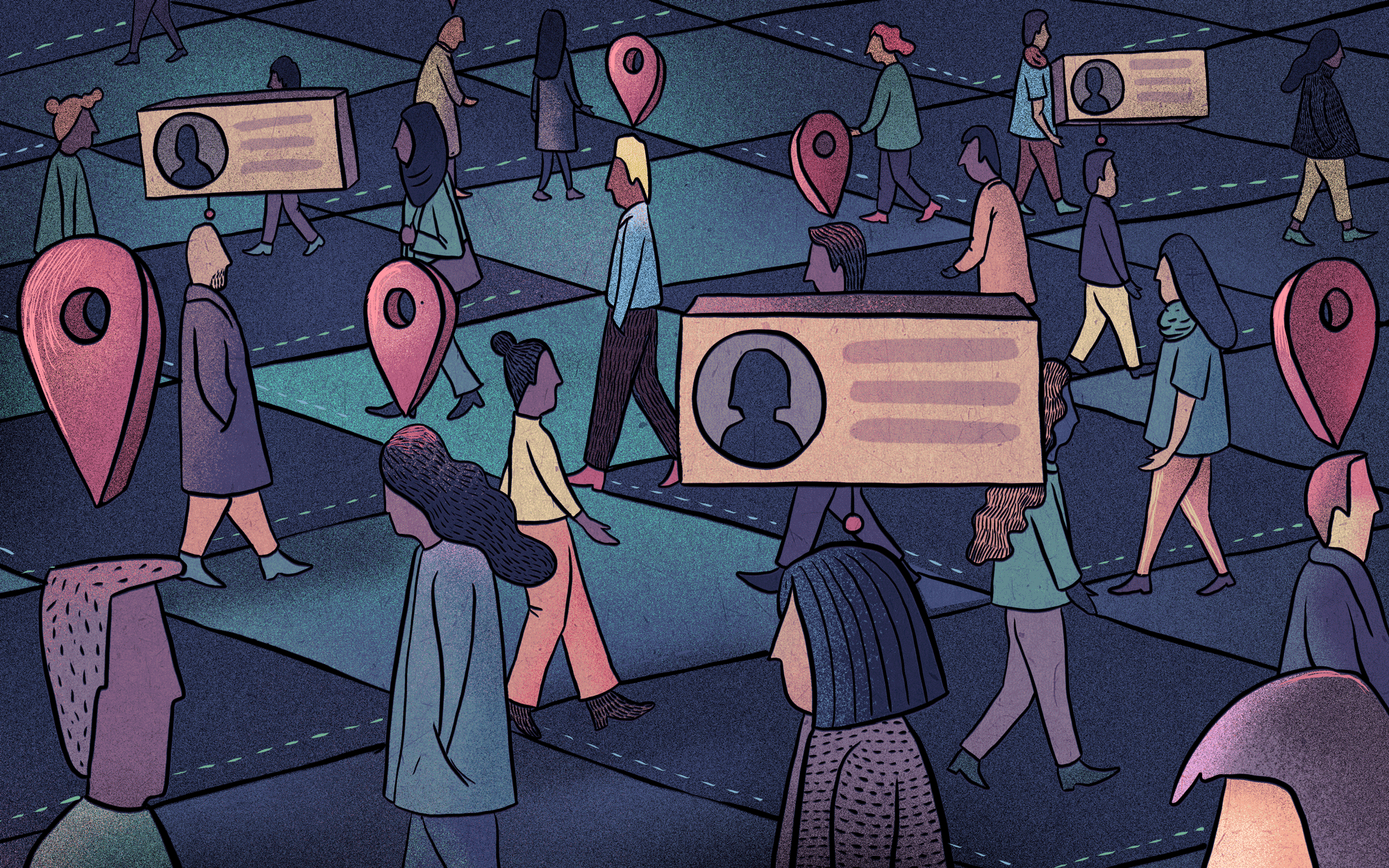

But once that surveillance goes beyond the government, what should the limitations be? The Thin Blue Line Project looks like technology we have all seen before — convenient geolocations; pinpoints on a map. In the hands of law enforcement and in an era in which the Department of Homeland Security monitors social media to conduct risk assessments, it could be considered legitimate—something that could be used to justify arrests or traffic stops. Moreover it’s a quick step from government to locals: If you can look up the traffic on Waze, why not the Islamic centers on TBLP?

It’s not that the information cannot be otherwise found or that it’s secret, but rather that the way it is packaged that makes it seem legitimate. Much in the way that Guandolo can use veiled threats to allege someone might be a terrorist, the Thin Blue Line Project makes every person who has been turned into a data point appear guilty by association. It seems to go against the credo of Silicon Valley to use technology and data as a way to promote racist surveillance. Twitter and other tech groups have already agreed not to participate in a Muslim registry—but if ACT has anything to say about it, the same targeting technology can come to fruition, with or without the Valley’s help.