M Niaz Asadullah

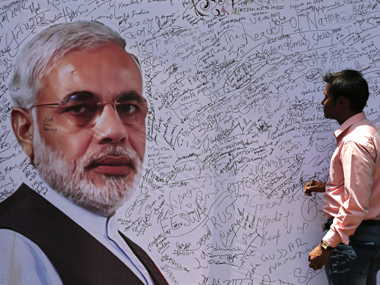

India under Modi faces a difficult development agenda. Despite significant economic growth from 1990 to 2010, progress on key Millennium Development Goals (MDG), particularly those in the areas of education and health, has been lacking. The country lacks social infrastructure such as toilets and schools. In Modi, Indians have chosen a leader who may be able to improve the country’s poor infrastructure, arrest the slide in governance, and give a much needed boost to economic growth. But will everyone share in the economic prosperity Modi is hoping to stoke? A comprehensive vision for India’s development must ensure that the basic needs of all of its population are addressed.

There is much to do to ensure India meets its human development needs. The under-provision of sanitation facilities is widely believed to be a key driver of under-nutrition in the country. A shortage of toilets means than nearly half of India’s population is forced to defecate in the open. In this respect, Modi’s state of Gujarat scores ahead of the national average. Gujarat increased the proportion of households with access to some form of latrine by nearly 13 percentage points between 2001 and 2011, which, while certainly an improvement, was less than the gains seen in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andrah Pradesh and Maharashtra, among other states. The proportion of households in Gujarat with toilets is higher than the national figure — 57 per cent of Gujarati households with toilets against the national total of 47 per cent. It is less impressive when compared to Bangladesh, which managed to dramatically cut the number of households without toilets in just 10 years, despite being poorer than India. According to World Bank statistics, only 4 per cent of the population in Bangladesh today practice open defecation, down sharply from 42 per cent in 2003. No wonder infant mortality in Gujarat is higher than that in Bangladesh.

While India has also made considerable progress achieving near universal enrolment in primary education, 19 per cent of Muslim boys and 23 per cent of Muslim girls are still not in school. Gujarat does stand out in some respects, with near universal (that is, 95 per cent) enrolment of rural children between the ages of 6 and 14. However, drop-out rates remain high and hardly anything is learnt in school, while the educational attainment of Muslim children is lower than that of Hindu children. In Gujarat, one report found that 55 per cent of children in fifth grade cannot read a second grade text and 65 per cent of children in fifth grade cannot do simple subtraction.

In addition, large gaps remain in education statistics between Hindu and Muslim children. Of all the Indian states, Uttar Pradesh is one of the worst in terms of Hindu–Muslim gaps in social and educational statistics. Yet Modi’s election campaign saw him shore up support in the state by whipping up Hindu anger again already disadvantaged Muslims.

As highlighted by the 2006 Sachar Commission Report on the socio-economic and educational status of Indian Muslims, key government facilities remain systematically under-provided in Muslim communities. Making progress on social welfare would require addressing these critical gaps in supply of public services.

For India’s consumer class who rely on the private school sector instead of the failing government schools, and who live in exclusive residential neighbourhoods, Modi’s role in the 2002 Gujarat riot does not carry much significance. Modi’s narrow development vision, which has largely ignored the limited human development progress in Muslim communities, has caused little concern among his Hindu nationalist followers. After all, Gujarat’s economy grew significantly over the past decade, compared to the economic stagnation during the period of Congress party rule in the 1990s. This has arguably benefited Hindus and Muslims alike in terms of income and employment. But evidence for the success of Modinomics is unconvincing. Over the past three decades, the state of Kerala has seen much better progress in human development than Gujarat. Much of Gujarat’s growth was a legacy of history: the state was already growing when Modi assumed power. Most disturbingly, an invisible fence divides the city’s Hindu and Muslim population — an infrastructure boom in Ahmedabad has bypassed the city’s largest Muslim ghetto with a population of about 400,000 people.

The 2015 deadline for reaching the MDGs is around the corner. As Modi leads India into the post-MDG era, he must go beyond divisive politics and pursue a development agenda that equalises social opportunities for all, including the country’s 150 million Muslims. He must prove critics wrong by delivering roads, schools and hospitals to under-served neighbourhoods and villages irrespective of their religious composition.

Such an inclusive approach at this critical juncture would have long-lasting positive effects on India’s progress in social development.

Source: Bd news24