Why Tunisia’s transition succeeded

Tunisian President Kaïs Saïed has appointed Elyes Fakhfakh to be prime minister on January 20. Fakhfakh, who served as tourism minister following the revolution, and then as finance minister in 2012, will have one month to form a government, the Project on Middle East Democracy* reports.

One of the main reasons democratization succeeded in Tunisia while failing in other Arab Spring countries is the country’s strong civil society, according to a new Afrobarometer* analysis.

In 2010, when protests escalated and reached the capital, civil society groups, trade unions, lawyers, journalists, and opposition parties joined the uprising and played a key role in ending 23 years of authoritarian rule, note analysts Thomas Isbell and Mohamed Najib Ben Saad:

POMED

After the revolution, the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet – made up of the Tunisian General Labor Union; the Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts; the Tunisian Human Rights League; and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers – was awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for successfully negotiating a compromise between secular and Islamist political actors when the democratic transition was close to collapse due to intense political polarization. Politicians agreed to overcome their differences and achieve consensus that gave space to both Islamists and seculars in the new political system.

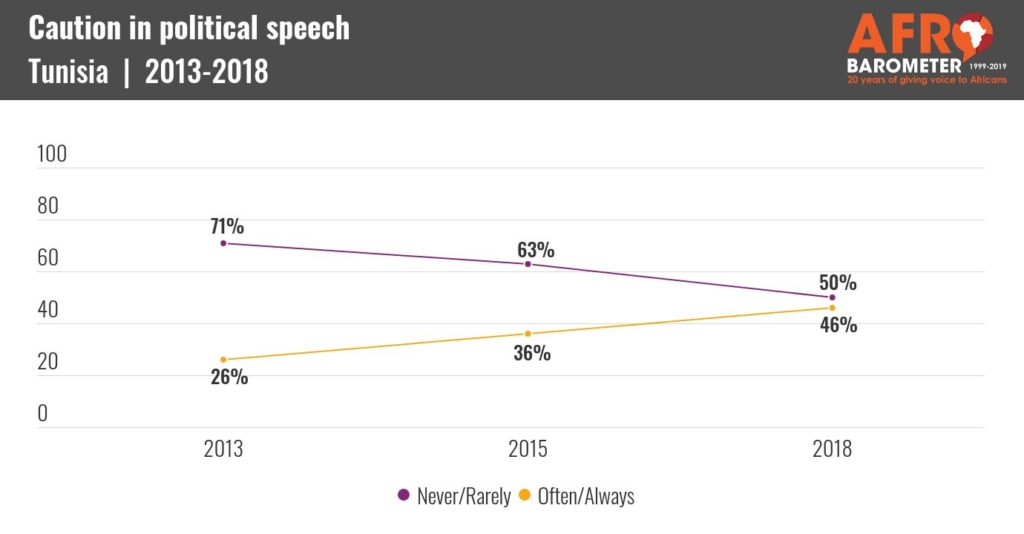

Using Afrobarometer survey data to explore citizen engagement, they find that while a majority of Tunisians say civic and political liberties have expanded in recent years, the proportion of citizens who feel restrained in discussing politics has increased, and fewer are going to the polls on Election Day. Even though a growing number of Tunisians express a willingness to join together to raise an issue or to participate in a protest, in practice only small minorities engage through civil-society organizations or contact with their leaders. RTWT

International Republican Institute

Since the 1980s, decentralisation has been championed as a driver to develop marginalised peripheries in Arab countries, notes analyst Intissar Kherigi. In practice, many decentralisation efforts ended up as mere transfers of authority from a central state to an under-resourced and over-burdened local government, with limited positive effects to citizens. She explores whether a renewed push for decentralisation in Tunisia can finally address the demands for inclusion and development. In order to succeed, central state institutions need to fundamentally reform the way they function, Kherigi adds in an article published in collaboration with Chatham House.

In December 2019, members of Tunisia’s civil society attended a European Endowment for Democracy Panel discussion (below) entitled “An evolving role for Civil Society within Tunisia’s new political reality?” to discuss perspectives for change in Tunisia and the potential role of civil society in this new post-election period.

*A partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).