16 DAYS OF ACTIVISM AGAINST GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE

In 2015, Salma’s husband and his parents held her down and poured nitric acid down her throat because they wanted more than the Tk 100,000 (USD 1,100) that her parents had already paid in dowry. For months since the wedding, her father-in-law had beat her repeatedly, demanding more. Salma went to stay with her parents to escape the abuse. But when villagers started gossiping about her broken marriage, her parents told her to return to her in-laws. When she said she was being physically abused, they told her “you just need to endure.” Now, she is fed through a tube in her stomach.

Salma’s story is disturbingly common in Bangladesh, where over 70 percent of married women and girls have faced some form of intimate partner abuse, about half of whom say their partners physically assaulted them. But the majority of women never told anyone about this abuse and only three percent take legal action.

In many cases like Salma’s, survivors seeking help are turned away—by family, community, and the police—and can be in even more danger when forced to return to their abuser. When Salma tried to escape the violence, she was met with stigma and—with only a handful of government-run shelters in the country and limited access to support services—she had nowhere else to go.

Salma has fought for a legal remedy for over five years now, but to little avail. Her father, meanwhile, had a stroke and the family cannot afford to continue pursuing justice. The public prosecutor bringing the case told her that her in-laws were paying more bribes so she “should pay more money.” “That is how you will get justice,” he told her. He too, of course, requested bribes, she said.

Every time they go to court to find out the status of the case, court officials, police and the prosecutor all ask for “tea and snacks costs,” Salma said. Now she says she is telling her father, “You have been going to the courts for the last five years and nothing is happening. Let’s just give up.”

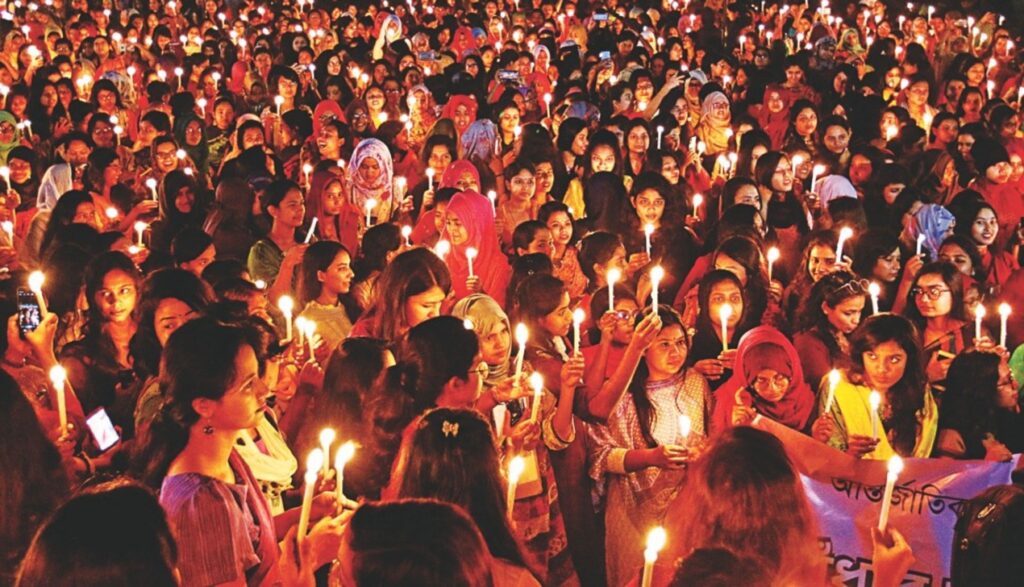

The 16 Days of Activism is an annual international campaign in which governments and activists come together to address violence against women and girls. It runs from November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, until December 10, Human Rights Day.

The Bangladesh government should work with concerned donor governments, activists and the UN to conduct an audit of currently available shelters, disseminate this information, and commit to opening at least one shelter in each of Bangladesh’s 67 districts by 2025. Shelters should remove restrictions that limit their accessibility, such as requiring court orders to stay there or restricting the presence of children. No woman or girl should ever have to “just endure” violence because there is nowhere else to go.

The law ministry should immediately create an independent commission to appoint public prosecutors to ensure their independence. Donor governments like the US that are involved in justice reform should ensure that training for public prosecutors and police emphasises working with victims of gender-based violence and consider joint training for prosecutors and investigating officers to improve coordination on cases of gender-based violence.

As Salma described, as cases go on for years, justice officials frequently demand bribes, making it more and more difficult to continue to pursue justice. This problem is exacerbated by a lack of transparency and accessibility of case information, given Bangladesh’s 3.7 million-case backlog. Without a centralised filing system, cases get lost and survivors are forced to pay bribes to get court officials to find their case information and move cases forward. The German government led an impressive justice audit in Bangladesh and would be well-placed to spearhead a project to move case files into a centralised online filing system—gender-based violence cases would be a good place to start.

The Bangladesh government should ensure that legal aid is reaching women and girls in need and that they are aware of their rights. Last year, the national legal aid services organisation distributed funds to 2.5 times more men than women.

The law commission drafted a witness protection law nearly a decade ago—it should be passed into law in consultation with Bangladeshi women’s rights organisations, and donor governments should support the implementation of a witness protection programme.

Violence against women and girls is so pervasive in Bangladesh, it is sometimes dismissed as unsolvable. For these 16 days of activism, the government and donors should listen to activists who are offering workable solutions.

Meenakshi Ganguly is South Asia Director at Human Rights Watch.