South Asia Used to Be the World’s Fastest-Growing Region. Now It’s Facing an Economic Slowdown.

Weak domestic demand is hurting growth, but more investment could lead to a rebound.

Welcome to Foreign Policy’s weekly South Asia Brief. The highlights this week: A troubling new World Bank report, India lifts some communications restrictions in Kashmir, Pakistan’s Imran Khan to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and an effort to rekindle the Afghan peace talks.

South Asia is experiencing a “sharp economic slowdown” because of a drop in domestic consumption, according to a World Bank report released this week. While each of the region’s eight economies is projected to keep growing, South Asia has already fallen from its perch as the world’s fastest-growing region, replaced by East Asia and the Pacific.

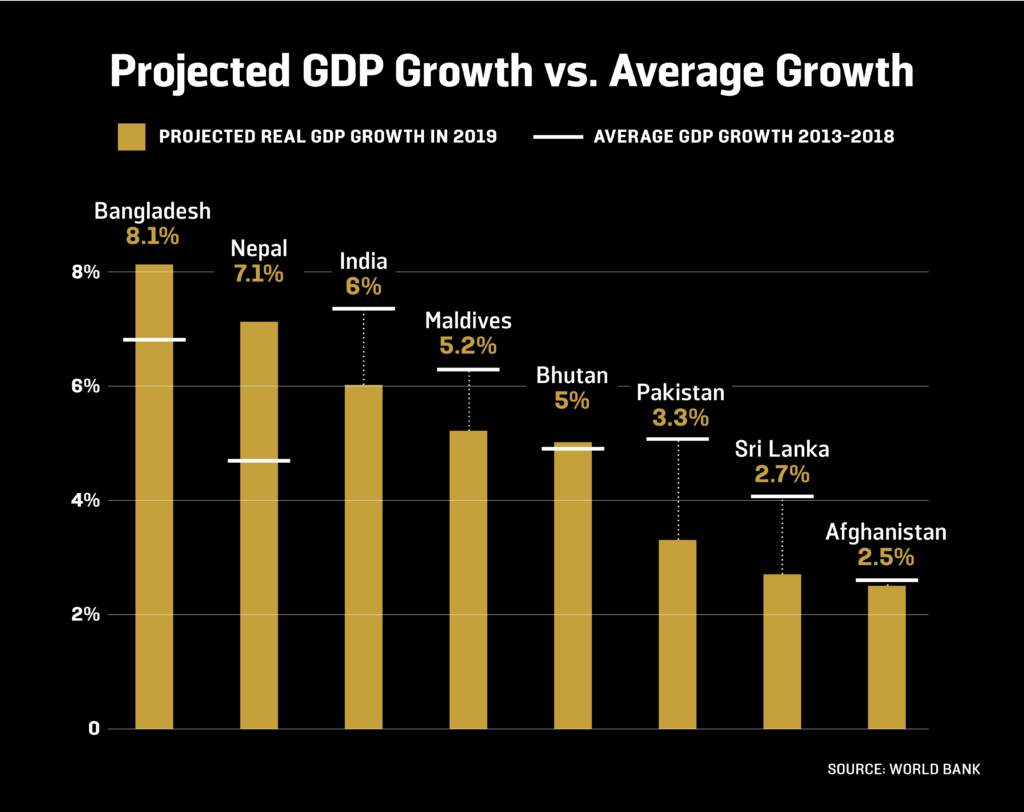

Of all the countries in the region, the World Bank slashed India’s growth forecast by the most, from 7.5 percent to 6 percent for the fiscal year that began in April. Bangladesh and Nepal, on the other hand, had their growth projections revised upward, but only slightly. As shown below, every country—barring Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan—is now growing at a rate slower than its recent five-year average.

What’s wrong with India’s economy? South Asia’s biggest economy is the area of greatest concern. The World Bank report cited a drop in private consumption growth—from 7.3 percent a year ago to 3.1 percent in the last quarter—and negligible manufacturing growth as the main reasons for India’s slowdown. The findings are no surprise: There has been a steady drumbeat of worrying data for months. GDP growth has declined for five quarters, unemployment is at a 45-year high, car sales fell by 31 percent in July—the sharpest drop in 18 years, rural consumption has plummeted, and exports have remained flat.

Deeper malaise? In a recent lecture at Brown University, Raghuram Rajan, the former chief of India’s central bank, said that “India’s financial stress should be seen as a symptom rather than a sole cause.” While Rajan went on to list the causes as a drop in investment and consumption, he also called out two moves by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government: the so-called national demonetization in 2016, when the two highest currency notes were recalled, seizing up the country’s mostly informal economy, and the botched rollout of a national goods and services tax in 2017. Those two moves, Rajan said, represented “the straw that seems to have broken the Indian economy’s back.”

No easy fix. One ray of light in the World Bank report is that South Asia’s current slowdown echoes similar slumps in 2008 and 2012. As in those cases, the recommendation is that a boost in investment and private consumption could lead to an acceleration of growth. The bank also called for more effective decentralization in the region’s economies—but as evidenced by Modi’s surprise 2016 cash recall, the biggest economic decisions have been highly centralized.

Another opinion worth noting is that of Parakala Prabhakar, a think tanker and the husband of India’s finance minister, who wrote in the Hindu on Monday that Modi’s government has spent too much energy rejecting the socialist policies of previous governments without making clear its own economic vision.

What We’re Following

Kashmir calling. After launching a communications blackout in Kashmir ahead of its repeal of Article 370 in August, India’s government may be starting to loosen its grip. On Monday, it restored phone service to about 4 million mobile phones without internet connections. Prepaid phones, and those with internet services—the majority of devices—are still offline. Without cellular data and internet connections, Kashmir, some residents say, had become a virtual prison.

[The internet blackout has been especially difficult for students, who have been unable to register or study for exams, Yashraj Sharma reports for Foreign Policy.]

Imran the mediator? Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has been busy recently trying to marshal criticism of India’s handling of Kashmir into some kind of international response. But now he is picking up another diplomatic cause: mediation between Iran and Saudi Arabia. During a visit to Tehran on Sunday, Khan offered to pave the way for talks between the two rivals. His trip to Iran (and to Saudi Arabia later this week) comes after a request, he said, from U.S. President Donald Trump to help “facilitate some sort of dialogue between Iran and the United States.”

All talk. On Sunday, the Wall Street Journal reported that the United States was pushing to restart peace negotiations with the Taliban, including by sending U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad to Pakistan to meet with Taliban leaders. Their discussion reportedly touched on a possible prisoner swap and ways to reduce ongoing violence in Afghanistan. It is unclear whether the Taliban could deliver on such a promise, given the complexity of the conflict and the number of terrorist organizations operating in the country. Last week, Afghanistan’s intelligence service announced that it had taken out a top al Qaeda commander during a strike last month that had also killed civilians attending a wedding party.

Empty promises? Last weekend, the leaders of India and China met in Mamallapuram, India. The flashy summit included lavish gifts and plenty of photo-ops. But in terms of substance, it was lacking: a few agreements to hold future talks and not much more. That is not entirely surprising, Sumit Ganguly argues in FP, as India has a much weaker hand: Its economy is much smaller, and it has relatively weak regional alliances.

Question of the Week

Today, Foreign Policy holds Her Power, its inaugural global women’s summit bringing together leading voices, unsung heroines, and trailblazers in international policy and business. The program looks to gender equality as a way to build stronger democracies.

While South Asia records dismal numbers on some indicators—female literacy, for example—it has had surprising success in breaking the glass ceiling for female prime ministers and presidents. Which was the first South Asian country to be led by a woman?

A) India

B) Bangladesh

C) Sri Lanka

D) Pakistan

Scroll down for the answer.

South Asia Inc.

Going for gas? France’s Total announced this week that it will pay $866 million for a 37.4 percent stake in India’s Adani Gas as it seeks to expand its foothold in the country. The move comes as India pushes to invest in greener sources of energy, with as much as $60 billion invested in natural gas infrastructure in the coming years, Reuters reports.

Forbes Rich List. India’s broader economic woes have hit its billionaires, too. According to the 2019 Forbes India Rich List, the total wealth of the tycoons profiled has dropped by 8 percent since last year. Reliance Industries Chairman Mukesh Ambani remains the richest in India, with a net worth of $51.4 billion.

Odds and Ends

Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, who share a 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics with Michael Kremer, answer questions during a press conference on Oct. 14 in Cambridge, Mass.Scott Eisen/Getty Images

A Nobel for the neediest. On Monday, Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Michael Kremer, of Harvard University, were awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics. Banerjee, who grew up in Kolkata, and Duflo, who is the youngest-ever winner and the second woman to win the prize, were recognized for their “experiment-based approach” to ending global poverty.

In a 2011 FP article, Banerjee and Duflo discuss their work: “What we’ve found is that the story of hunger, and of poverty more broadly, is far more complex than any one statistic or grand theory; it is a world where those without enough to eat may save up to buy a TV instead, where more money doesn’t necessarily translate into more food, and where making rice cheaper can sometimes even lead people to buy less rice.”

Simple solution. Cataracts are the leading cause of blindness in the developing world. The condition is generally curable, but in remote or poor places, it is often unaddressed. In Nepal, one ophthalmologist has created a simple technique to produce new lenses and a stitch-free procedure to swap them out, Al Jazeera reports. Sanduk Ruit developed his treatment in 2014. Since then, he’s increased production to around 500,000 lenses per year, and his team sees around 300 patients a day.

Her Power—Women’s employment in U.S. foreign-policy agencies has decreased steadily since 2008. Original research by FP Analytics tracks the lack of progress toward gender equality through extensive data analysis, one-on-one interviews, and focus groups with current and former female U.S. government employees in foreign policy.

Read the Her Power Index to see what we uncovered about the barriers women face entering the field and rising to leadership positions.

And the Answer Is…

C) Sri Lanka.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike was elected Sri Lanka’s prime minister in 1960, becoming the world’s first nonhereditary female leader. She served three terms, 1960-1965, 1970-1977, and 1994-2000.

India’s Indira Gandhi was elected in 1966, Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto in 1988, and Bangladesh’s Khaleda Zia in 1991. Bangladesh has since had another female prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, who was elected in 2009 and remains in power.