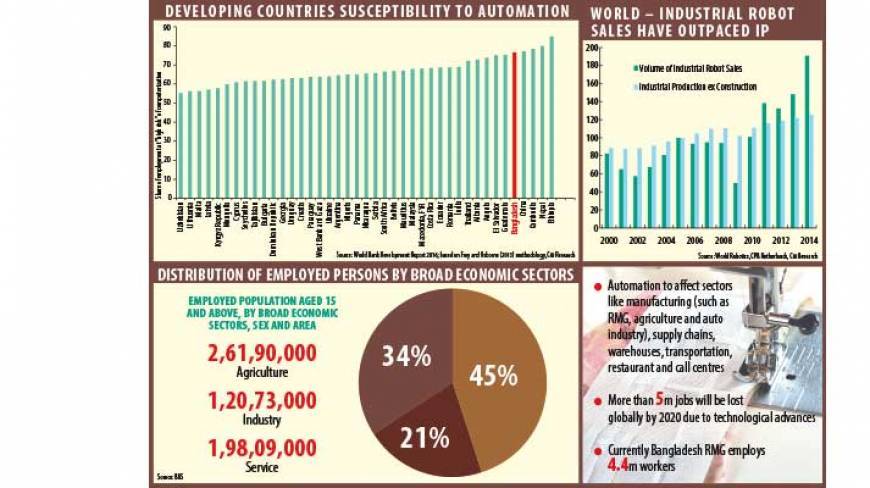

Rising automation and use of robots in industrial production will put the world’s poorest nations at risk, with 70% of all jobs in Bangladesh in danger of being lost over the next decade, says a new analysis.

The impact of automation may be more disruptive for developing countries due to lower levels of consumer demand and limited social safety nets, according to a research released last month by Citibank, the US bank, and the Oxford Martin School, a research and policy unit of the UK university.

It said Nepal, Cambodia, China and Guatemala are among the other countries most at risk ahead of Bangladesh from “premature deindustrialisation.”

The findings come a week after the World Economic Forum estimated that more than five million jobs will be lost globally by 2020 as a result of advances in artificial intelligence, robotics and other technological changes.

“Bangladesh has nothing to worry about rising automation,” said Prof Shamsul Alam, president of Bangladesh Agricultural Economists’ Association.

“Rather, I prefer automation to increase productivity, which can be used for creating jobs in other sectors that will compensate the labour displacement in particular industries,” said Alam, also member of the General Economic Division of the government’s Planning Commission.

Sectors like manufacturing including RMG, agriculture and auto industry, supply chains, warehouses and transportation, lower-end service jobs, restaurant and call centres will face negative human employment in near future, according to the report titled Technology At Work v2.0.

“Technological changes are expected to further impact employment in the media and telecom sectors, while cloud computing could have a significant impact on IT employment.”

Although robots will replace a number of jobs, they will also generate new positions. The International Federation of Robotics estimates that growth in robot use over the next five years will result in the creation of one million high quality jobs around the world.

“There are many other new and emerging jobs that are being created and will continue to be created over time … we focus on two particular industries which are growing – the health sector and the environmental/green sector,” said the research.

The susceptibility to automation across the developing world ranges from 55% in Uzbekistan to 85% in Ethiopia.

“Due to an increase in automation in manufacturing, low income countries will not achieve rapid growth by shifting workers from agriculture to factory jobs,” said Carl Benedikt Frey, co-director of the Oxford Martin programme.

As robots become smarter, faster and cheaper, they will be doing tasks that go beyond repetitive, dull, and dangerous and will be used in other industrial sectors besides the auto industry, where today’s majority of industrial robots are used, the report says.

According to Boston Consulting Group projections, at least 85% of the production tasks in the robotic-intensive industries can be automated.

At present, lower-income countries have a competitive cost advantage over higher-wage ones in tradable sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing.

However, the report argues that they will lose the edge as robots replace workers, levelling the cost playing field. Moreover, their current low wage levels mean poorer countries still have a greater number of easily automatable jobs that will ultimately be lost.

In addition, the rise of automation and technological developments such as 3D printing will encourage companies to bring manufacturing back to their home countries.

The report cautions that manufacturing is becoming less labour-intensive in the emerging and developing world, contributing to a growing concern over “premature deindustrialisation.”

In most of sub-Saharan Africa, manufacturing sector’s share of output has persistently declined over the past 25 years.

Measuring impact of automation, the report says that across advanced economies, labour productivity growth has slowed from 4% in 1965-75, to about 2% from 1975-2005 and 1% from 2005-2014, with no sign of a pickup in the most recent data.

Worse still, while the full impact of automation is likely to take longer to reach developing countries than richer ones “it may be potentially more disruptive in countries with little consumer demand and limited social safety nets”, says Carl Benedikt Frey.

Source: Dhaka Tribune