How to empty Bangladesh’s secret detention cells

David Bergman September 10, 2021

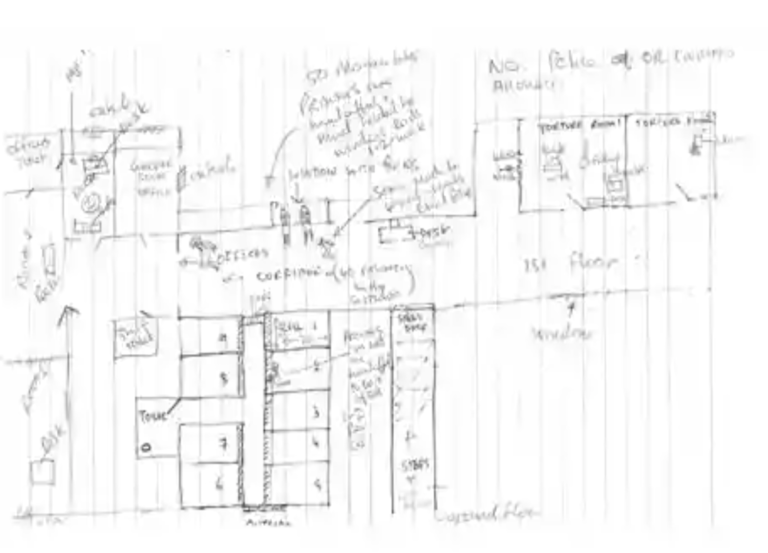

secret detention cells in Bangladesh, drawn by a person who was detained there.

The Bangladesh government must think it has more to gain from continuing to pick up and secretly detain political opponents, perceived dissidents, alleged militants and suspected criminals, than the reputational damage it continues to earn through its involvement in these enforced disappearances. While national outrage is present though muted, international criticism by human rights organisations remains strident and well publicised — but this is clearly not substantial enough for the government to change its policy. And though it is law enforcement foot-soldiers that do the dirty work, it is only senior Bangladeshi politicians, who can bring this practice to an end.

Evidence suggests that the most high profile of the disappearances are specifically authorised by the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina — for example the abduction and secret detention of Hummam Quader Chowdhury, who was picked up by the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI).

Other disappearances are more likely to be directly sanctioned by leaders and commanders of the various law enforcement and intelligence agencies who conduct the abductions — that is to say DGFI, the Rapid Action Battalion and the police (particularly the Detective Branch, better known as the DB) — but many if not most of these are quite clearly authorised at a political level. For example, just before the 2014 national elections, 21 opposition party activists were picked up in and around Dhaka by various law enforcement agencies — mostly RAB and DB — over a course of two weeks. Seven years later, 18 of the 21 men remain missing. It is difficult to imagine that these 21 abductions were not done with very clear political direction and authorisation at the highest political levels.

This is not to say that there are not some freelance efforts by the law enforcement agencies or powerful political leaders with a degree of control or influence over the agencies. The abductions of the staff and family of the retired army officer and UK-based businessman (and now trenchant political dissident) Shahid Uddin Khan , who is the subject of a vendetta conducted by Major General (retired) Tarique Siddique, the prime minister’s security advisor and Khan’s former business partner, is a perfect example of this. In these disappearances, there was no state/governmental interest involved — though the private interests of a powerful politician certainly were.

The government’s response to the overwhelming evidence of state involvement in these adductions is simple denial, with a range of absurd and easily refutable claims. These were most prominently articulated by Sheikh Hasina’s son and advisor, Sajeeb Wazed Joy in an article in The Diplomat and more recently by Bangladesh’s ambassador to the United States, Shahidul Islam, in a letter to the US Congress’s Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission. Islam’s letter made the following points:

— The Bangladesh government is “committed to addressing any allegations of human rights violations in the country.”

— “[W]e have … investigated the matters with due seriousness”

— In many cases “‘perceived’ victims have reappeared proving the allegations of so-called ‘enforced disappearance’ false.”

— “They discovered that many of the ‘disappeared’ were in hiding, evading prosecution for violent crimes.”

— “‘miscreants’ … use the name and disguise of law enforcement agencies like the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) to carry out such ‘abductions’ or ‘kidnappings’” and so the government is not responsible

— The Government has also “examine[d]” cases when “there are allegations of extrajudicial killings and have concluded in almost all cases that those were without merit.”

— The police have also “investigated instances of reported extrajudicial killings disappearances. They have found no evidence of government involvement.”

— “While Bangladesh takes seriously and investigates every reported disappearance, it cannot, logistically or legally, give credence to anonymous sources that make such allegations [in the Human Rights Watch report].”

First, the Bangladeshi authorities do not undertake any kind of proper investigations into disappearances. One should, of course, not be surprised at this, as they are themselves involved in undertaking them! In the rare cases where any kind of investigation is done, it is just for show, and they are not intended to find out what had happened. Since the state does not investigate them, it is simply ridiculous to suggest that these “investigations” have “found no evidence of government involvement.”

Secondly, most of those disappeared do not even have criminal cases against them, so why would they go into hiding?

Thirdly, if all these men were picked up by criminals pretending to be law enforcement agencies, why are not the actual enforcement agencies undertaking concerted investigations after each of these disappearances to locate these “disguised” gangs of men?

Fourthly, while it is certainly the case that a good percentage of the men who disappeared do re-appear after a period of time, this is not because they were never picked up, but because they have been released after weeks or months of secret detention. These released men are then usually immediately re-arrested and sent to jail officially. The others who are released onto the streets, are too scared to recount publicly what happened to them, though privately they do.

What is going to stop Bangladeshi law enforcement agencies conducting disappearances — and indeed releasing those held in the country’s secret jails? Human Rights Watch research suggests that the whereabouts of at least 86 men remains unknown.

There is no prospect that internal pressure in Bangladesh will impact upon the government stopping disappearances , or those disappeared being released. And if there has been any informal diplomatic pressure on the Bangladesh government, it certainly has had no impact so far, and is unlikely to do so in the future.

There is however one new strategy that could force the government to rethink its role in disappearances as well as in extrajudicial killings. This is the imposition of travel and financial sanctions against senior law enforcement officials and those within the government authorising them.

The UK now has a new law that allows it to impose travel and financial sanctions for those involved in human rights violations and recently a group of UK-based international lawyers made a submission to the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office seeking sanctions against senior Bangladesh political figures — understood to include Sheikh Hasina herself — as well as commanders of relevant law enforcement agencies. In the United States, where similar powers have existed for many years, Netra News has heard that a similar submission has been made, though details of this have been kept confidential. In addition, in October 2020, a bipartisan committee of Congress called on the US government to impose sanctions on RAB commanders.

Recently, newspapers have reported yet another apparent disappearance, that of Rizwan Hasan Rakin, a Bangladeshi student from Egypt’s Al-Azhar university who was picked up at Dhaka’s international airport as he arrived in the country in early August. His whereabouts remains unknown for over a month.

Imposing sanctions on relevant politicians and law enforcement officials may well be the only action that will force the Bangladesh government to empty its secret detention cells, releasing the men currently languishing there, as well as to stop its strategy of enforced disappearances , many of which end in extrajudicial killings.●

David Bergman (@TheDavidBergman) — a journalist based in Britain — is Editor, English of Netra News.