In the stumbling block of concrete mess at Moghbazar, Minhaz Abedin waits patiently every day, worrying about his unemployed son, something he has been doing for the past three years now.

He has no clue when this flyover will complete. Every day, he hopes his patience will not run out this time. His retirement comes up next year when he turns 60 and then he does not know how he will sustain another 10-15 years of his life he hopes to live.

Meantime, the project overruns its cost by many hundred crores of taka.

Minhaz’s experience makes part of Bangladesh’s development story today.

The country has suddenly burst into project activities and rightly so as it pathetically lacks the infrastructures — usable roads, flyovers, metro rails, expressways, power stations, ports and so on. Suddenly, billions of dollars seem just like a piffling sum. Investors and creditors are lining up ready with the cash.

The economy is doing much better than before with a prolonged macroeconomic stability. Inflation is low thanks to the global slump; interest rate — a main contention of the businesspeople — has come down considerably; foreign exchange reserve is good; and debt burden is low.

A perfect happy story altogether. Very welcoming. Except if you glance at the gathering gloom under the boom. Somehow, these positives of the economy are not being translated into investment.

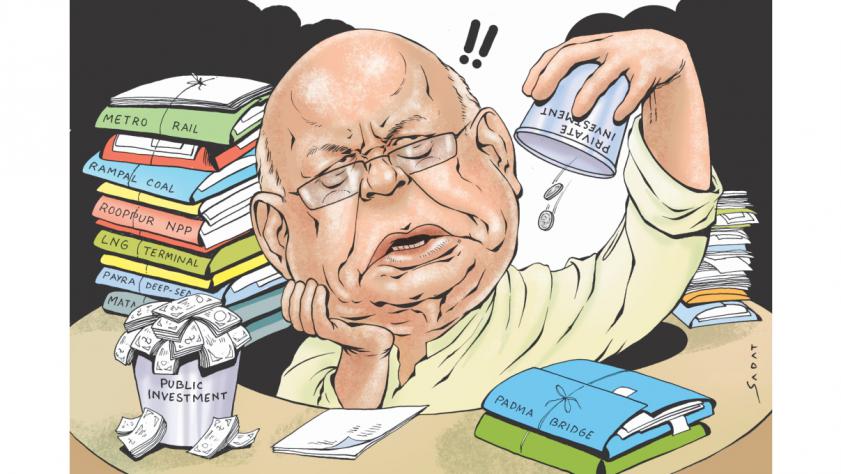

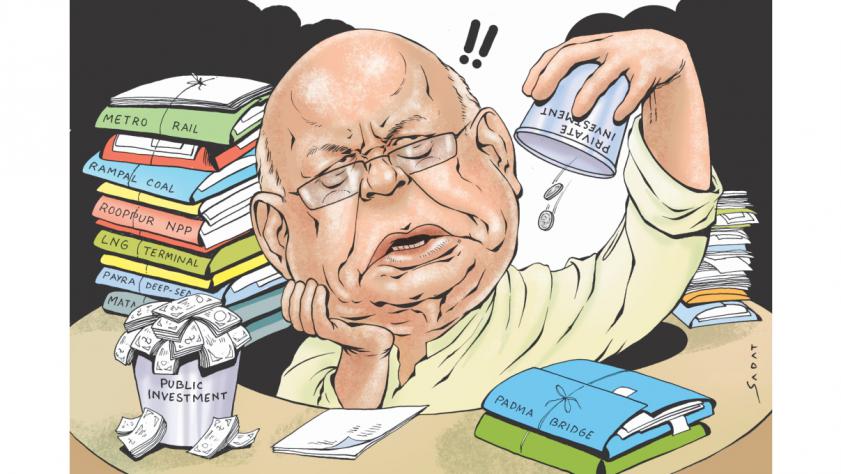

Public investment in mega projects is growing fast, however. But each and every vital mega project is taking more than their estimated time to complete. And with time, their costs are rising.

This spells serious repercussion on their economic rate of return and our fiscal management. We are getting the same road but at a much higher cost; the same flyover at an exorbitant price. We could build almost two Padma bridges with the cost of one. This simply does not make any business case.

There is no doubt that Bangladesh needs a big budget to get on to higher growth. But it does not have to mean waste of resources. The concern should now be whether we can do more projects with the same money.

The method of investment is also debatable. The government is going for relatively costly source, namely savings certificates, while cheap money is lying idle in banks.

At the core of this delay are the inefficient bureaucracy and procedural cumbersomeness.

Bangladesh has been unsuccessful in galvanising its bureaucracy that has been politicised heavily over the years. The inefficiency is now costing heavily as our development budget gets bigger and bigger. One may be well-trained to fly a small Cessna. But you cannot expect him to fly the Dreamliner with the same training. Otherwise, how can you explain the delays? Or the pathetic 50 percent implementation of the Annual Development Plan in 10 months?

In the following two months, a big chunk of the ADP will be pumped out, leaving out the question of quality. In the end, everybody would look at the figures; the real roads and markets will turn into projects and the projects into figures of 90 percent or so.

Talking about figures, who cares if figures do not reconcile with other supporting numbers as has been the case of GDP growth this year. The World Bank was the first to point out that the growth indicators do not support a 7.05 percent GDP growth this year.

Whether numbers reconcile or not, some serious matters are surfacing on the horizon in the fiscal side because of the trends. Revenue collection has fallen short of target — and there is little chance of any future jump — while expenditure has increased quite a bit. Exports have declined, and the weak global conditions imply risks for exports and workers abroad. As debts pile up on account of big projects, incomes fall.

For the first time in history, Bangladesh is going to enter a high debt trajectory with poor income situation (its revenue intake as percentage to GDP is the second lowest after Nigeria, as FitchRatings measures). This may pose a serious fiscal problem and maybe the possibility of a debt overhang although many would debate that Bangladesh still has a lot of fiscal space. The big $28 billion foreign exchange reserve is also a breathing space, for now at least. But what would happen when payments on the debts begin is something to ponder about.

On top of this, unemployment, especially of the educated class as faced by Minhaz’s son, is nagging constantly. Every year, about 3,00,000 jobs are being created but that’s hardly enough for the two million new entrants in the job market. Jobless educated youths pose political and security risks to any country.

Unemployment has its roots in the lack of investment and the nature of investment. Not very surprisingly private investment has dipped as public investment has gone up. Entrepreneurs are weary to invest and you cannot blame them when Bangladesh fares poorly in the World Bank’s governance indicator (it ranks 174th among 189 countries in the Bank’s Ease of Doing Business report).

Cost of doing business is high as rent seeking or in simple words corruption pervades. This is eroding competitiveness and making investment cumbersome and risky. No wonder capital flight continues unabated and companies from Singapore, Canada and Dubai regularly hold seminars in top Dhaka hotels about how to get citizenship through investment.

An interesting feature of this year’s estimated growth shows a major part of it would come from the service sector which probably explains the unemployment question partly. As we know service sector does not generate as many jobs per every dollar as industries do. So growth comes but not jobs.

For populous countries like Bangladesh, it is important to have activities that employ people. While the economy has to be modernised, the development has to come in a balanced way. Against the background of the global torpor it would be important for the government to perk up industrial activities, especially in the small and medium category.

But these fiscal deficit, debt overhang or rent seeking matters little to Minhaz who worries about his own long retired life ahead. Bangladesh’s demographic change is dramatic. With improved healthcare and higher nutrition intake, people now live up to 70 years.

But that has posed another kind of problem. As they retire at 60, they still remain active for a long time to come with health cost increasing.

With no pension scheme for the private sector — both formal and informal — and meagre sums for the public sector, the retirees slump into hardship as the capital market is anything but reliable and strong, deposit rates are low and other scopes of income limited.

Beyond various safety net programmes introduced by the government to help various disadvantaged groups, it is becoming a serious concern as to how to take care of the grey population.

So while we go on a joyride there are bumps ahead. Unless we have the seatbelts fastened the riders could be tossed off the trail.