‘It felt like I was in a grave’

Finally home, after 53 days of enforced disappearance and 7 months in prison, photojournalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol talks to Zyma Islam of The Daily Star about his ordeal

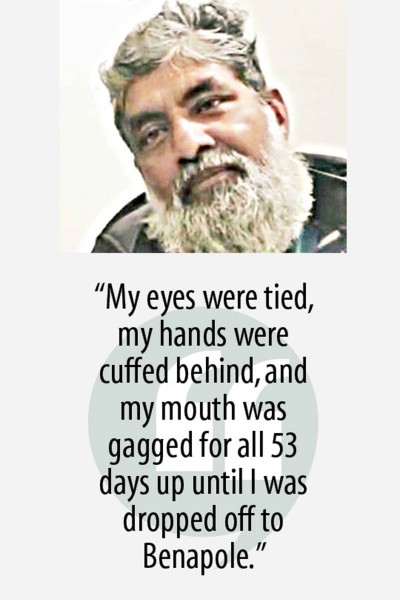

“I decided not to shave the beard. I’ve just trimmed it a bit, I think I quite like the beard,” laughed Shafiqul Islam Kajol, his eyes twinkling with amusement at the irony of keeping the large, shaggy, grey beard that grew out over his 53 days of enforced disappearance and seven months in prison.

“But I could not find my old barber at the spot where he used to sit, so I had to go to a new one…” he added in postscript — a sobering reminder of the months that were taken from this photojournalist’s life.

Kajol had disappeared on March 10 last year and was “found” by the Border Guard Bangladesh roaming around the Benapole border 53 days later.

He would then land in jail for three Digital Security Act cases filed by lawmaker Saifuzzaman Shikhor, and two Jubo Mahila League activists for a Facebook post.

And finally on December 17, the HC ordered bail in two remaining cases after his lawyer pointed out that the probes into his cases had to be concluded within 75 days of filing of the cases, and the investigators had failed to do so.

He was released on December 25.

Kajol now walks with a shuffling gait, his whole body aches at night, and his mental health is in shambles — but at least he is home.

However, so many questions about his ordeal still remain, and talking with The Daily Star, Kajol answers some of them. But far more worrying, are the details he chose not to disclose.

“It felt like I was in a grave,” is how he described his 53-day disappearance. “It was a very small enclosed space with no windows,” he said.

“My eyes were tied, my hands were cuffed behind, and my mouth was gagged for all 53 days up until I was dropped off to Benapole. I only kept count of the days. That is it.

“It was indescribable. I spent my days thinking about my family and whether I will ever see them again.

“I feel like I have died and come back.”

He, however, did not divulge details of who was keeping him and where. Asked about the conditions of his confinement or what kind of exchanges he had with his abductors, Kajol also chose to keep these details to himself.

He just said: “My whole body was in so much pain. I carried that pain all throughout Jashore jail and Dhaka Central Jail.”

Kajol warns against blaming the whole administration about what happened to him.

“I am most probably a victim of a personal vendetta. This was a conspiracy made by certain people who are only a small part of the government… one cannot blame the whole administration, the law enforcement agencies, or anyone else. The blame solely lies with the few people who orchestrated this, and I recommend that investigators find out who they are.”

53 DAYS IN CONFINEMENT

Kajol said he was picked up in front of Bangla Academy.

“I was going towards a political office where I often spend certain evenings,” he said.

At the Bangla Academy, he was surrounded by a group of bikers comprising men in civilian clothes, he said. “Around 10 minutes later, two minivans showed up and I was blindfolded, gagged, and taken in.”

Nobody contacted his family about ransom at any point.

He spent 53 days in confinement until one day Kajol was loaded onto a vehicle again and driven towards Benapole.

Asked about how long the journey took, he could not tell since he was blindfolded the entire time. “They shoved me out of the van warning me to stay quiet. I roamed around for a while before the BGB found me,” he said.

The Raghunathpur unit of Border Guard Bangladesh claimed they discovered Kajol in a paddy field in Raghunathpur village of Sadipur union, walking into Bangladeshi territory around 12:45am on May 3. The spot where he was found is directly adjacent to the border and the Benapole Land Port.

Asked why his abductors released him and why they chose Benapole, he said, “I honestly don’t know why I was released. I think they wanted to push me across the border.”

That would still not mean freedom for him, as the journalist would be spending the next seven months in jail, fighting the Digital Security Act cases filed against him.

A probe was not done nine months after the cases were filed, even though the Digital Security Act mandates that investigations into these cases be completed within 60 days, with a probable extension of another 15 days.

In addition, even though Kajol was placed under arrest the very day he was found, so that investigators could probe the Digital Security Act cases against him, any legal step to investigate the conditions of his disappearance is yet to be taken.

For a single Facebook post, he was denied bail a total of 13 times, according to Article 19, a human rights organisation.

Three of those rejections were when a virtual court discovered on June 14 that Kajol was not yet formally “shown arrested” under the Digital Security Act cases, even though he had been arrested and imprisoned since May 3.

“What was my fault that I had to be denied bail for nearly a whole year?” he questioned.

7 MONTHS IN PRISON

And the jail conditions during that time — while an improvement from the conditions of his involuntary confinement — took a toll on Kajol’s mental and physical health.

“The Jashore Central Jail was good… they were humane. Dhaka Central Jail was the exact opposite,” he described.

At Dhaka Central Jail, the “gono room” he stayed in was a jail cell stuffed with everyone who could not pay for space and food. They inmates were assigned cleaning and maintenance jobs to compensate for the shelter they were receiving.

“There were inmates who could get restaurant food delivered to them, whereas I could not even see my son once,” he said.

Kajol also said his phone calls from the jail were monitored. “I was allowed a minute or two, and the calls had to be made in front of an officer.”

While waiting for freedom every second, Kajol read voraciously in the jail library to distract himself from thoughts of his family.

All his thoughts revolved around how his family — his cancer-survivor wife, his 20-year-old son, and school-going daughter — was surviving now that their breadwinner was languishing in jail.

“Over the phone, I could not muster the courage to ask my son whether they have money for household expenses. I would just ask, ‘Baba, do you have enough for rent this month?'”

For now, Kajol wants to rest, heal, and receive medical treatment. “But in the future, I want to get back to work.”