By Adil Khan 12 September 2023

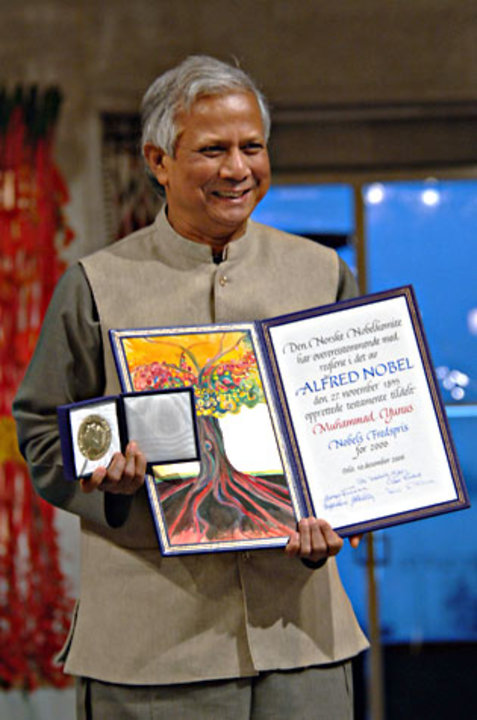

2006: Professor Muhammad Yunus with the Nobel Peace Prize

While the Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus has many admirers, he is no stranger to insults either, especially in Bangladesh.

Yunus has been a target of insults and harassment for a while, more prominently and visibly since 2009 and in recent times, the pattern of these insults has undergone an important change – the sources of insults have moved from individual to collective.

Actively promoted by a section of civil society, the media and even the academia, the Yunus insults have become somewhat of an enterprise.

With the 2024, election looming, and West’s especially that of the America’s pressure on the government mounting to hold a free, fair, and inclusive election under a non-political care-taker government and as their demand to stop violence against the opposition also became resolute, the Hasina government and their cohorts have become nervous and edgy over people who they suspect to be the instigators of these threatening actions. Some of them firmly believe that Yunus, who has friends in the US establishment has played a role in shaping the US government’s hard position on the Hasina government.

There are also those who passionately believe that the US government is preparing for a regime change in Bangladesh where they may put Yunus in charge.

These are pure speculations and there is no evidence to support any of these claims, but that has not stopped the speculators reacting nastily.

Lately, the government has also accused Yunus, falsely, of tax fraud and neglect of employee rights and has prosecuted him. This has alarmed the international community.

167 Eminent World citizens that included former US president Barack Obama and former Secretary General of the United Nations Mr. Ban Ki Moon as well as several Nobel laureates who have termed these court cases against Yunus as “judicial harassment” have petitioned the Hasina government to stop harassing the 83-year-old Nobel Laureate Prof. Yunus, the inventor of the microcredit idea and asked the government to allow him to continue contributing to the mission of poverty alleviation and human development, within and outside Bangladesh. The petition has stressed that the signatories are “…concerned about his safety and freedom.”

Sadly, far from abating, the appeal has done the opposite has – more harassment and a collective cacophony of insults against Yunus by a section of civil society and the media have filled the air and the pages of the local newspapers that are under government scrutiny.

In their vilification campaign, the anti-Yunus crusaders have questioned Yunus’ Nobel bona fide and, in the process, have doubted the credibility and integrity of the selection of Nobel Peace Prize awardee.

In the meantime, the pro-government teachers at the Dhaka University, Bangladesh’s premium university, have petitioned the Nobel committee to retract the Nobel from Yunus.

The Yunus Insult enterprise has also made the claim that his microcredit idea is a sham, and that microcredit does not alleviate poverty, the raison d’etre behind his Nobel trophy. Instead, they argue, without evidence, that microcredit’s “high” interest rates make poor poorer. They thus call Yunus a “usurer” (“Shudkhor”) and a “blood sucker” (“Roktochosha”) of the poor.

These are serious allegations that warrant an informed response. Let us begin by exploring the issue of integrity of the Nobel Peace Prize, first.

Is the Nobel Peace Prize credible?

The Yunus Insults enterprise claims that Yunus did not deserve to get the Nobel prize and that he was awarded the Nobel prize because of the lobby of some powerful people. In other words, these antagonists doubt the integrity and accuracy of the decisions taken by the Nobel Committee.

Let us pause for a while and try and understand the processes the Nobel Committee follows in awarding the prize.

The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prizes goes through a lengthy process of nomination, scrutiny, selection, and finalization. Therefore, the allegations that the Nobel prizes are given whimsically and opportunistically and through lobby and not through any objective and thorough analysis are not true though this is also not to say that the Nobel Committee does not make mistakes and that their decisions are always rational. They certainly are not.

For example, I personally think that the Nobel Peace Prizes to Barack Obama and Henry Kissinger were misjudged. Neither did nothing to promote peace and on the contrary, did the opposite – patronized and intensified illegal and immoral wars overseas that killed and maimed millions and yet the Nobel Committee gave them the Nobel Peace prizes. This was wrong.

Regardless and notwithstanding these mistakes, can we say that the Nobel Committee wrongly awarded Yunus with the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize?

This also brings us to the question whether microcredit has been a credible and transformative idea and awarding Yunus the Nobel Peace prize the right thing to do? Let us try and answer whether microcredit works and whether microcredit is a universally proven tool of poverty alleviation?

Does microcredit work?

The quick and short answer to the question is that – microcredit works and there are loads of cross-cultural evidence that supports the theory.

Indeed, how about I share experiences of some of my personal modest engagements with microcredit, both as a practitioner and as an academic.

During 1997-1999 I, as the head of the UN Human Development Support Programme in Myanmar was involved in overseeing the pilot implementation of the microcredit programme in that country. The programme started on an experimental basis with only 500 borrowers and by the time I left Myanmar in 1999, the number of borrowers had increased to 7000 with 98% debt repayment and 0% dropout and the microcredit experiment of the UN in Myanmar has been so successful that the Myanmar government has since institutionalized the UN pilot project and made it into a poverty bank and has made it a country wide operation.

Then as a researcher-cum-academic I supervised 3 PhD students who worked on microfinance initiatives in two different countries. One of these students who examined the outcomes of microfinance in Bangladesh covered close to 300 microcredit borrowers of both Grameen Bank and BRAC – the two leading microcredit NGOs in Bangladesh – concluded that 85% of the borrowers of microcredit had benefited from the microloans; 7% became worse off; and 8% borrowers who were non-poor also benefitted from the microloans.

Some of the critics of microcredit cite “high” interest rate in credit operations as “extortions”. One the face of it, the critics seem to be saying the right thing. However, one must dig deeper to appreciate the issue of “high” interest rate in microcredit more insightfully.

It is true that in microcredit operations, interest is higher than that of the commercial banks and the logic behind charging higher interest rate is that microcredit is a labour intensive and high-risk operation and thus entails higher per unit cost of delivery and management of credit services, warranting higher interest rate.

Another way of looking at the issue of higher interest in microcredit is to acknowledge that in the absence of microcredit the only other credit option for the poor would be to turn to the traditional money lenders who charge anything between 100%-150% interest rate and with collateral, an arrangement that pushes the poor in perpetuity, into the debt/poverty trap.

By the way, during his field study when my PhD student raised the issue of “high” interest rate with the borrowers and asked them if they would prefer withdrawal microcredit facilities, the response was a definitive and resounding, “No” because they know very well that alternatives are either not their or suicidal.

It is thus reasonable to conclude that microcredit works and that it is indeed a revolutionary idea that has benefited many, globally and thus deserved international recognition such as the Nobel Peace Prize. Thus, the Nobel Committee did the right thing by awarding the 2006 peace prize jointly, to Prof. Muhammad Yunus, the inventor of the idea and the Grameen Bank, the institution that made the revolutionary idea a realizable goal.

Sadly, none of these seemed to have quite calmed the Yunus bashers in Bangladesh and what is also puzzling is that Prof. Muhammad Yunus who has many admirers both home and abroad, the Insult crusaders seem to be the ones having complete monopoly in the public information domain in Bangladesh these days. How come? Is Yunus friendless in Bangladesh these days?

Is Yunus “friendless” inside Bangladesh?

It is a known fact that inside Bangladesh Yunus commands a lot of respect and has many admirers and followers, and they include eminent economists, academics, researchers, and civil society leaders etc. Then why is that these Yunus venerated protagonists are so silent against the on-going barrages of misinformation and disinformation that are being spewed against Yunus by the Yunus Insult enterprise? Why are they playing the role of passive onlookers? How come? Have the Yunus admirers lost their courage and surrendered their principles?

May be not or maybe they have valid reasons for choosing to remain silent. Indeed, we may not have to go far and beyond to look for the reason.

A recent incidence where the Deputy Attorney General (DAG) of the Bangladesh government who refused to sign a government-initiated petition against Professor Yunus has been sacked summarily and the gentleman who feared for his life and safety of his family has since ended up taking shelter in the US Embassy in Dhaka. This reveals the incredible danger free speech and ethical action that contradict or have appearance of contradicting government position encounter in Bangladesh these days. This is sad but this is the cruel reality in the present-day Bangladesh.

In other words, the Yunus Insult Enterprise reveals a much bigger and sinister trend in the contemporary Bangladesh – a society where its respectable gets disrespected and its honourable gets dishonoured with impunity and with inspiration of the government and a society where fear of reprisals silence contrary views, is a society which is truly in decline in every aspect especially, morally.

The author M. Adil Khan is an academic and former senior policy manager of the United Nations