How India’s growth bubble fizzled out

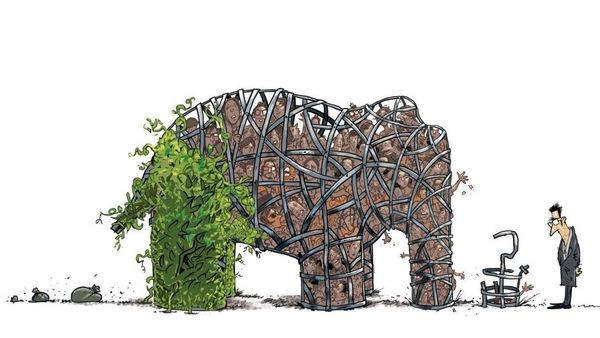

- The slowdown is not a short-term disruption. What can replace India’s finance-construction growth model?

- As the finance-led growth model collapses, India must invest in its future. India will need at least a generation to build necessary human capital alongside more productive urban spaces

India’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has slowed sharply from 8% a year last year to 5% in the second quarter this year. Optimists, Indian and international, say growth will pick up soon. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects the Indian economy will hum at 7.5% a year by 2021. Such optimism is dangerous.

GDP growth could, in fact, fall and languish in the 3-to-5% a year range. The ongoing slowdown is not a short-term disruption. Rather, a financial bubble that began inflating nearly three decades ago is finally fizzling out.

Indian policymakers have patted themselves on the back during these past growth years. They have relied on a narrow vision of economic liberalization, which could do little to generate long-term growth but which did create deep financial pathologies and inequalities.

Meanwhile, India has lagged woefully in creating the human capital and urban infrastructure needed for a modern, competitive economy. Without these prerequisites, India is bereft of a growth model. Here’s how India lost its way:

Liberalization misses its mark

On 24 July, 1991, the newly-appointed finance minister Manmohan Singh declared in rhythmic sentences: “Let the whole world hear it loud and clear. India is now wide awake.” India is an “idea,” he said, whose “time has come.”

Singh’s goal was to rejuvenate Indian industry. The two-pronged strategy included the carrot of a 20% rupee devaluation (bringing it to ₹26/dollar) and the stick of lower import barriers and more liberal rules for entry of foreign investors to “expose Indian industry to international competition.” Indian producers would need to pay attention to “cost, efficiency, and quality,” making them sturdier global competitors.

It was an important moment in global economic history. The East Asian “tigers,” especially Korea and Taiwan, had left India in the dust in the 1970s and 1980s during the first wave of international competition for labour-intensive production—electronics goods, garments, shoes. The tigers were now graduating to technologically sophisticated products. Could India fill the space opening up in labour-intensive production?

The economist Paul Krugman issued a warning. The Singh type of liberalization could improve the efficiency of resource use and, hence, give a “one-time economic boost,” but they could not generate long-term growth. The World Bank noted pointedly, East Asia grew through “broadly based educational systems” that “invested in people.”

Hence, under Singh’s liberalization, the action took place elsewhere. The stock market soared. The Sensex rose from about 1,400 on the day before Singh’s speech in July 1991 to 4,467 on 22 April, 1992—a three-fold rise in nine months. It was tempting to believe that the reforms were paying off. But the rise was fuelled by a financial scam perpetrated by the stockbroker Harshad Mehta, who borrowed illegally from banks to push stock prices up. The market stopped dead on 23 April when Sucheta Dalal of the The Times of India exposed the fraud.

Financial Magic

The pattern was set: quick riches through financial magic. In May 1994, Morgan Stanley established an Indian liaison office, employing the 37-year old, Harvard Business School-educated Naina Lal on the breathtaking annual salary of ₹1 crore (over $300,000 a year). Naina Lal’s income was about 40 times that of a secretary to the Government of India. Four new private sector banks entered the market in the early 1990s: Axis Bank, HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, and IndusInd Bank.

The man who captured the moment was Ravi Parthasarathy, a graduate of the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad and a former Citibank employee. Starting in 1987, he headed (under various titles) the Infrastructure Leasing and Finance Services (IL&FS). IL&FS was financed principally by government-owned or government-supported institutions. Because it did not receive deposits from the public, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) did not regulate it as a bank. The RBI did have oversight over the IL&FS because it was a “systemically important” financial institution.

But, charitably, the oversight was light. By the early 1990s, Parthasarathy figured out that real money lay in infrastructure construction projects funded by the central and state governments. Therein lay cozy deals, padded to make everyone happy—the politicians, bureaucrats, and IL&FS. No one was looking.

The bubble began to inflate. For the nearly three decades after Manmohan Singh’s economic reform, “finance and real estate” was India’s fastest growing sector. The other growth sector, construction, matched financial growth until recently (Figure 1).

In contrast, the manufacturing, at which Singh directed his reform effort, tread water. Through the 1990s, India steadily ceded ground to China, the emerging global export powerhouse of labour-intensive products.

The result: the Indian economy did a poor job of creating jobs. Labour-intensive manufacturing is the only source of good, steady jobs that create the prospect of upward mobility for workers and their children. Finance is glamorous and a few people receive outrageously large compensation, but the sector employs few people.

Construction did open up jobs for those moving out of low-productivity agriculture. But construction workers were low-wage casual labourers, who worked episodically in brutal conditions. No one looked under that hood either.

’Shining India’ years

Domestic policymakers and international observers celebrated the high headline growth numbers. Indian software producers gained disproportionate spotlight as markers of success. In March 1999, the Bengaluru-based Infosys became the first Indian-registered company to be listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange. In March 2000, the then US President Bill Clinton visited India, making a stop in Hyderabad, dubbed “Cyberabad” under the tech-savvy chief minister Chandrababu Naidu. Clinton spoke in awe of India’s dazzling diaspora in the US Silicon Valley; he applauded India’s young multimillionaires.

Some months before Clinton’s visit, in October 1999, a BJP-led coalition had gained a stable majority in the Lok Sabha. But the essential philosophy established by Manmohan Singh—more open markets, financial deregulation—remained unchanged.

India now decisively missed the second wave of global competition in labour-intensive products. When, on 11 December, 2001, China became a member of the World Trade Organization, Chinese exporters powered into the new markets opened up to them.

India’s finance-construction growth model continued apace. In 2003 and 2004, two new private banks, Kotak Mahindra and Yes Bank, joined the crowded financial field. The BJP built more highways, which created more need for private finance and gave more fillip to construction. The barely hidden nexus of politician, bureaucrat, and financier became tighter. India steadily became one of the world’s most unequal economies. The BJP’s 2004 Lok Sabha campaign with the slogan “Shining India” felt hollow and cynical to far too many people.

Human capital

Losing to international competition in this second wave failed again to bring home the message that India lacked a core ingredient of success: human capital. From the time of the industrial revolution in the late 18th century, economic growth and human capital development had been closely related. Each round of successful new entrants on to the global stage had pushed the human development frontier further.

The Americans achieved near-universal high school education in the early 20th century and they followed it up after the Second World War with the spread of state-financed universities. The East Asians understood this historical lesson well.

Even for labour-intensive manufacturing, quality and timely production required a high degree of industrial literacy. East Asian—including by now Chinese—schools got steadily better; the governments there began the task of building world-class universities.

In India, the illusion continued. The years 2003 to 2008 were heady. Although China was chewing up export market shares, it was also a major importer of raw materials and industrial products. Thus, the Chinese boom fuelled extraordinary global trade volumes. The entire world rode that rising global tide—and so did India.

When the global financial crisis made its impact in 2008, Indian policymakers steadied the domestic economy through fiscal stimulus, and the fiscal boost continued for a few years, creating the sense that India had escaped the damage. India’s growth momentum had, however, lost steam—the apparent pick up after 2014 being a statistical artifact of a new methodology that paints a rosy picture completely at odds with the reality.

Chinks in growth model

Without the boost to world trade between 2003 and 2008, the cracks in the finance-led growth model would likely have become evident much earlier. After about 2004, the employment situation, already grim, became dire. Between 10 and 12 million young Indians enter the workforce every year. However, recent data from the National Sample Survey Office suggests that the Indian labour market has produced no new net jobs since 2004.

Construction has continued to offer men some new jobs. But women, especially from financially vulnerable households, have withdrawn from the workforce, given limited opportunities in agriculture and rural industry.

By the mid-2000s, a vast swathe of Indian manufacturers had given up. Rana Dasgupta, in Capital: The Eruption of Delhi, interviewed a young auto parts producer in a grotesquely lavish Delhi farmhouse, who said, “What you see in front of you is the wealth from my real estate. Not from my automotive business.”

As China moved upscale, India lost out in the third wave of international competition in labour-intensive products. Vietnam began taking over China’s space in electronics, garments, and textiles. Bangladesh’s garment exports zoomed ahead of India’s garment exports. The magic ingredient? Still human capital. Vietnamese children are among the very best in the world in science in tests conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) under its Programme for International Student Assessment; in mathematics, they are at the OECD average, above France.

Bangladesh has entered a virtuous cycle of labour-intensive production, greater female labour force participation, and better educated children, especially girls. Indian school performance results make for depressing reading: even in advanced states like Tamil Nadu, only about one-third of 5th grade children can read at the second-grade level; only about a quarter can divide. And there is no evidence that performance is improving over time.

Financial bubble is imploding

No surprise. The implosion started with IL&FS, now a behemoth with several dozen subsidiaries shrouded in opaque financial accounts.

As Sucheta Dalal documents, the infrastructure lender IL&FS spread its tentacles in mysterious ways, employing civil servants in “special purpose vehicles” administering the infrastructure projects it financed. The civil servants and IL&FS executives enjoyed an extravagant lifestyle, enjoying the patronage of powerful politicians while avoiding the scrutiny of the RBI. IL&FS is the most egregious example of the finance-construction-politics nexus. The rot though is widespread and is chewing the entrails of many public sector banks, whose accounting is also hidden from view. Despite recent recapitalization of these banks by the government, their stocks trade at between 0.3 and 0.6 of their book values, implying the market’s judgment that large chunks of their assets are worthless.

Many observers predict—hope—that the current economic slowdown is temporary, and that growth will resume soon. Those more concerned call mind-numbingly for more “labour-market reforms,” not recognizing that increasing numbers of organized-sector workers are on precarious short-term contracts.

No, as the finance-led growth model inevitably collapses, India must invest in its future.

There are no easy fixes: India will need at least a generation to build necessary human capital alongside safer and more productive urban spaces. Or else, we will be looking down an abyss.

Ashoka Mody is a visiting professor at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School. He is author of Euro Tragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts.

The article appeared in the Live Mint