TBS

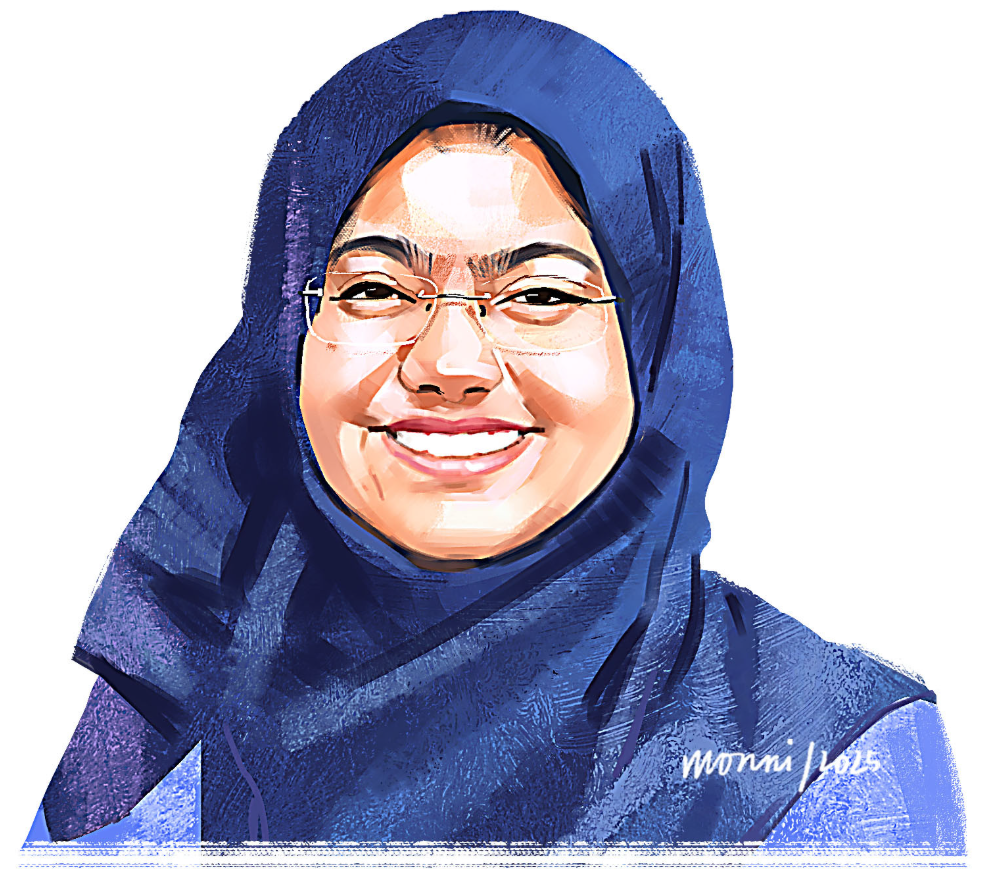

Dr Nabila Idris, a BRAC University teacher and member of the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh, discusses the challenges of the inquiry, the culture of denial, and the families’ enduring hope for truth and accountability

To mark the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances on 30 August, The Business Standard spoke to Dr Nabila Idris.

Idris, a BRAC University teacher, is also a member of the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances in Bangladesh.

Formed by the interim government in August 2024, the commission is investigating cases from 2010 to August 2024 under the Sheikh Hasina regime.

Your work — both through the commission and your personal platforms — has brought attention to the brutalities faced by victims of enforced disappearance. How challenging has this journey been for you and your team?

Compared to the challenges faced by the victims, ours pale in comparison. We speak to victims every day, and after those conversations, we no longer feel like talking about ourselves. I have two disabled members in my family. On top of that, managing the commission’s 24/7 schedule is difficult. But whenever I feel overwhelmed, I think about the victims.

For example, I recently spoke to a victim — his mother is dying of cancer. When he disappeared, he was only a third-year university student — there was no logic to why he was targeted. Most likely it was a local issue. He could not secure a job as he could not complete his education, so now he does daily labour to cover his mother’s treatment costs.

To him, this burden has become an even bigger issue than his disappearance itself. Through him, I realised he had been held in the TFI cells of the RAB Intelligence Wing, at a time when it was a demonic institution.

We have seen state-sponsored abductions carried out for political reasons, but evidence also shows that many innocent people with no political connections ended up as victims simply because of petty disputes or rivalries.

It is insane. For example, abducting big businessmen to extort money from them. Or a land dispute — someone tips off DGFI or RAB, claiming he is a big terrorist, and they simply make him disappear.

The most dangerous part is that this was happening simultaneously with the arrest of real terrorists. Terrorism is a genuine problem in the country, but when innocent, ordinary people were falsely branded as terrorists, it became impossible to distinguish who was a threat and who was not, especially when covert methods replaced proper legal procedures. You cannot just randomly declare someone guilty.

Recently I spoke to a police officer against whom there were many allegations. When asked to explain, he simply said, “I only caught terrorists.” He did not deny committing enforced disappearances or torture, he only tried to justify the actions by labelling the victims as terrorists. When I pointed out that there was no proof, he replied, “It can never be proven — you just have to trust my word.”

This way of operating has gravely damaged the country’s national security. We had actually triumphed over JMB, and they were eliminated without resorting to enforced disappearances. They were tried and executed under the criminal justice system. That was the right way.

What is the official mandate and timeline of the commission? What have you achieved so far, and what remains to be done? Do you anticipate needing an extension?

Our current mandate runs until 31 December 2025. I think the biggest problem that the Awami League created and nurtured is a culture of denialism around enforced disappearances. Much like some in the West who deny the Holocaust, the Awami League propagated the narrative that enforced disappearances, or Aynaghars, did not exist.

By the second report, our main objective was to challenge this denial with solid data, so that anyone observing in the future can clearly see that the denials are baseless. For that, from over 1,850 files, we sorted around 250 where a General Diary (GD) existed — something rarely allowed at the time — or there was a media report. In cases where the person reappeared, we could identify their whereabouts during the disappearance.

Our achievement lies in building a robust database that proves coordination across 15 years, among people of different professions and locations, is real — even when they did not know each other.

We also broke the culture of impunity: for example, the DG of DGFI had to flee, despite military leadership being informed in advance about the arrest warrant. This was a national security failure, yes, but it demonstrates that impunity no longer exists. People now genuinely fear facing justice, which will have a deterrent effect in the future.

Have your recommendations been acted upon meaningfully? For instance, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) still operates — has there been any accountability? Has DGFI faced any scrutiny? What about the involvement of other security agencies or political actors?

So far, it’s a mixed bag.

For example, at CTTC and DGFI, I wrote requesting the names of the directors of a particular bureau. They replied that they did not maintain an honours board and therefore could not provide the information. The response was largely meaningless — they sent one or two names, but couldn’t fully deny the information because the situation didn’t allow them to.

We also asked CTTC for the names of guards on the floor of a secret detention cell. They initially claimed no such cell existed. When we mentioned that we had visited the cells ourselves, they acknowledged their “mistake”.

Even so, the fact that “new Bangladesh” compelled these powerful forces to respond at all is significant — it shows progress, however modest.

The commission recommended the dissolution of RAB. But it continues to exist. And there are also questions regarding the DGFI.

Over the last 16 years, these agencies have been operating completely outside their mandates, often in a whimsical and farcical manner. Take RAB, for example, a composite force where military personnel are involved in civilian affairs. Where else in the world has this produced anything positive? It is also harmful for the military, because such tasks fall outside their training.

When a military officer is assigned to RAB, he is not there as a bad person. I do not believe many of the personnel sent there were inherently corrupt. But when they are commanded to carry out tasks beyond their training and understanding, both the victims and the officers themselves suffer. This is not just a disservice to the victims; it undermines those who joined the military with patriotic intent.

DGFI, in particular, must return to its original charter of duties. Following its proper mandate would have protected the country from being compromised, as happened over the past 16 years. Victim profiles even show cases where individuals were sent to India — those meant to protect the country instead facilitated these actions.

The way we create this composite force and deploy military personnel in civilian affairs is a flawed strategy. Officers engaging in these crimes, as noted in our second interim report, also become vulnerable to blackmail.

DGFI, in particular, must return to its original charter of duties. Following its proper mandate would have protected the country from being compromised, as happened over the past 16 years. Victim profiles even show cases where individuals were sent to India; those meant to protect the country instead facilitated these actions. Returning to their proper mandate is essential, though I cannot say how much of this is currently being implemented.

Mayer Daak reports over 150 cases where the victims’ whereabouts remain unknown. Has the commission investigated these cases? Roughly how many such complaints are currently on your docket?

We currently have over 1,850 cases. The cases of those who never returned are particularly heartbreaking. I deeply understand the pain of these families. In various interviews with perpetrators, I often emphasise that the families cannot give up hope — but hope, in itself, is a dangerous thing.

Dealing with these victims is truly harrowing. For example, some individuals involved in killing missions do not even know whom they have killed. It’s not that they are hiding it — they genuinely do not know. How can we then expect to learn more about the victims from them? This uncertainty itself is terrifying.

The system was deliberately segmented: one team detaining, another incarcerating, others carrying out killings. Perhaps, as a hadith suggests, one day will come when those who kill do not know why, and those killed do not know why. This was exactly the reality over the past 15 years.

It is extremely difficult to determine the fate of those who never returned, especially given the non-cooperation of the agencies. They are not making open calls to speak out, and as a result, many families may never receive answers. I must place responsibility for this squarely on the agencies.

The victims’ families — particularly the wives — want to know if they are widows, how the state will acknowledge them, and what compensation they might receive.

The commission has submitted recommendations on how the law should be amended to the Chief Adviser, and, as far as I know, these have been forwarded to the Law Ministry. One of the major issues is property: how it will be divided and how money in banks will be allocated.

This process needs to be expedited, made seamless, and the timeframe reduced. We have identified the necessary legal changes and included them in our recommendations, which also emphasise compensation for the families.

In terms of surviving victims, it is difficult to imagine the extent of the destruction in their lives. One victim recently told me about a Bollywood song he cannot bear to hear because it was played during torture in secret cells.

Another one cannot stand the smell of Lux soap because it was used in the washrooms of these cells. The impact on the education and careers of victims — often young and primary earners in their families — has been extraordinary. There is simply no way to compensate them enough for what they suffered.

While enforced disappearances under Hasina were unmatched and inhumane, this practice was reported in Bangladesh even before. What structural reforms are needed at the state level to ensure this culture of impunity ends permanently?

Enforced disappearances were extremely rare before, so the scale under Hasina is not comparable. It’s important to understand that the practice was used to normalise a form of fascism.

Since “crossfire” incidents were already drawing attention, the perpetrators cleverly ensured that bodies were not produced. This was entirely a novel practice, and the necessary infrastructure was built accordingly.

To prevent its recurrence, agencies must strictly adhere to their mandates. However, the most crucial factor is political will. Even the media was not exempt from this system — agencies would feed stories, and the media often repeated them without question. If all state agencies and the media operated strictly within their mandates, this problem would be solvable. But none of it is possible without genuine political will.