Climate Action: Sustainable Floating Cities

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS: Unconventional and seemingly extreme responses to climate change, related sea-level rise, and floods are gaining considerable attention, with the goals of creating adaptable homes and reducing mass migration.

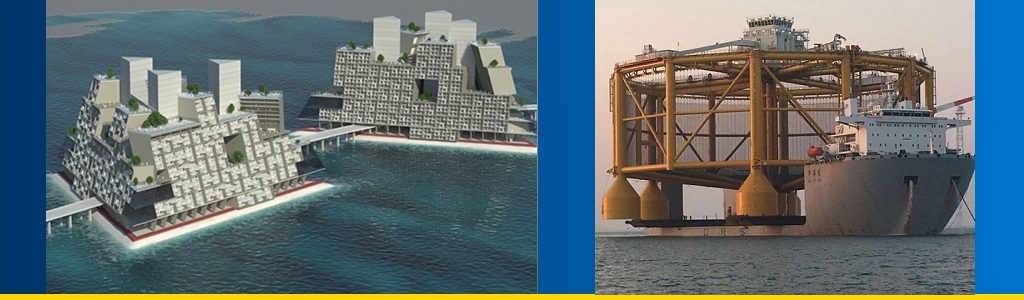

In April, the United Nations hosted a high-level roundtable on “sustainable floating cities” in New York City, and Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed requested advanced proposals for September’s UN Climate Action Summit. Ocean engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, along with architectural firms and organizations with ties to Denmark, French Polynesia and the United States, are drafting designs for such a “sustainable floating city” with a low ecological footprint. Of particular interest is a large floating structure’s resilience to floods and sea-level rise for many coastal cities, settlements near river deltas, and islands in Oceania and elsewhere in the world.

The plan is less eccentric than it might initially sound. Several thousand offshore oil platforms with living quarters and cruise ships have operated in the world’s oceans for decades. The yet undefined term “floating city” can refer to a variety of large floating structures that could be combined. Inspired by oil platforms, a free-market libertarian US-Thai couple built a small, offshore floating homestead off Phuket in Thailand earlier this year. Weeks later, the Thai navy ended that attempt to escape state control. In 2018, Russia launched a floating nuclear power plant, the Akademik Lomonosov. China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation constructed the first, semi-submersible fish farm, Ocean Farm 1, for a Norwegian company, SalMar, raising 1.5 million salmon several miles off the Norwegian coast.

These examples of mass producible floating industrial structures suggest that technology is not the challenge but rather globalization and the future of the ocean commons as well as sustainability, waste, legal issues, funding and business models.

Climate change, or rather its consequences, is not a really new element in the cost-benefit calculations. During the 1960s and 1970s, a small number of plans and prototypes for floating communities were released, and such analyses addressed temporary or permanent relocation of people, promotion of energy alternatives to carbon fuels, increased food production, and a state’s extension of judicial control over such offshore facilities. US and Japanese governmental agencies and designers wrestled with what is actually considered cost or benefit in their calculations related, for example, to cheap prices of air pollution-causing carbon fuels and aesthetic versus structurally efficient designs.

The UN roundtable panelists are in a quest for a sustainable floating city as a tool for climate action and resilient refuge. The goal is for permanent settlements rather than temporary fixes. A modular design is expected to allow growth in capacity and capability over time, similar to the growth of onshore cities over time. Design and flexibility will determine whether floating refuges turn into permanent settlements with reasonable living standards or slums, reminiscent of longstanding refugee camps intended as temporary solutions.

Inevitably, a floating city will be a centrally planned megastructure and, similar to an aircraft carrier, difficult to restructure. Aware of the problem, designers since the 1970s have argued for a plug-in system of mobile and rearrangeable trapezoid- or hexagonal-shaped floating modules, as advocated at the UN roundtable, to allow flexibility. For many, this recalls the rapid “urban renewal” development around the world during the mid-20th century. In neglecting actual human needs, the central planning and cost-benefit calculations easily led to dystopian spaces. Critics of urban-renewal projects during the 1960s, like journalist-activist Jane Jacobs, but also prominent architects, such as Christopher Alexander, pointed out that such planning and calculation failures resulted in residential spaces that were artificially separated from commercial or recreational spaces, isolating communities at night, and exacerbating crime and transportation problems.

As a reaction to urban projects in coastal cities, US designer Buckminster Fuller and his associates proposed Triton City, a floating community for unused harbor space, and released a study in 1968. That design still featured concepts that had been attacked by critics, likely because even a modular megastructure limited its flexibility: commercial and recreational space was prearranged with shops, restaurants and supermarkets in specific locations, again reducing pedestrian traffic in residential parts after daylight hours. To address crime, Triton City was proposed as a gated community, featuring guarded access points like a cruise ship. Designers must consider how choices add to social and economic problems if they aspire to offer more than dystopian, temporary solutions.

Fuller’s idea received noteworthy criticism from Gaylord Nelson, best known as the founder of Earth Day. In October 1969, this Democratic senator from Wisconsin and staunch environmentalist warned that within one decade unchecked human commercial enterprises might kill off most ocean life, and he pointed to the disastrous Santa Barbara offshore oil spill that had taken place that year. He also saw floating cities as another major threat, expressing concern that such structures could be located beyond US territorial waters – meaning that federal laws on conservation would not be applicable. The global proclamation of contiguous and exclusive economic zones ended such concerns of insufficient state control.

Enforcement of a legal framework is essential for sustainability. The Thai Navy ending the free-market libertarian experiment off Phuket illustrates that states capable of enforcing judicial control over their marine regions will do so – although this does not say anything about their offshore conservation standards. Monitoring the activities of fixed floating structures is, technically and legally, easier than monitoring transit vessels like cruise ships. Other free-market libertarian groups like the San Francisco–based Seasteading Institute therefore do not expect to escape state control without negotiations. The group focuses on building a startup floating city through private investments, without funding from the host state. In exchange, they ask for private judicial control over a special economic zone harboring the community, placing it outside the state’s tax and penal systems.

Reaching true sustainability is a related challenge. The international community, first and foremost UN agencies for now, must discuss the legal framework under which a sustainable floating city would operate as well as financing. In countries that cannot afford the funding, the choice would be between development assistance, private investment capital – with or without privately or publicly administered special economic zones – or a combination. The related legal framework must define the sustainability of economic activities, for example related to the use of huge amounts of cooling water. Regulators must consider if offshore server farms, zero-carbon nuclear power plants or waste incinerators comply. The same question is related to other economic activities like tourism.

Many structures struggle for sustainability. At the UN roundtable, participants advocated for a combination of renewable energies; hydroponics, or growing plants in a water solvent; and ocean farming. Yet, many business models of mariculture are unsustainable. For offshore wind turbines and other renewables such as solar, technical challenges like energy storage for times with low winds or night hours, may possibly be overcome via a kind of pumped hydroelectric energy storage using ocean water. In some cases, high costs for connecting to energy grids remain.

For now, floating structures are individual sites tasked with specific industrial or commercial purposes. They do not try to fully emulate cities with their intricate systems of cooperation, culture and justice around a range of vibrant activities. Supporting further research on ocean-related sustainable economic practices and on affordable, flood-resilient housing would be valuable as the United Nations considers sustainable floating cities as climate action in September – even individually, these would reduce the human impact on oceanic ecosystems and assist people living in flood-prone regions.

Stefan Huebner is a Social Science Research Council–funded Fellow at the Harvard University Asia Center and a Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. He is finishing a global history of ocean industrialization and colonization projects since the early 20th century.