Stories of income cut, unemployment, hunger, and renewed struggle in the capital amid Covid-induced downturn

Abdur Rahim*, a private tutor in Dhaka, thought his life had finally stabilised after two decades of hard work. With a steady income, he could afford a place in the capital and sustain his family.

But the stability he achieved was lost after coronavirus arrived on the country’s shores in early March, destroying the very means of living as the tiny microbe upended all aspects of public life, work, and education.

His tutoring came to a screeching halt when the government closed educational institutions in late March to contain the virus spread. He was lucky to have survived the disease, but he soon went from having a healthy stream of income of around Tk 60,000 a month to absolutely nothing.

“I was in complete dark about how my daily expenses would be met,” said the 51-year-old, who had lived in Tejkunipara for over two decades.

He got married in 2000 and their daughter was born five years later and all was well until the outbreak of Covid-19.

In the first two months of shutdown, his family lived on small savings. But as the savings ran out, he stopped paying house rent and took loans to meet living expenses.

In the face of mounting pressure from lenders, Rahim sold a small piece of land in his village home in Gaibandha in September for Tk 4 lakh, with which he cleared the house rent and repaid the lion’s share of the loan.

With all the money spent and no other options left, he packed up and vacated the house on November 30, selling out the benches, tables, and chairs. He went to Gaibandha in search of work while his wife and daughter moved to her brother’s house in Gazipur.

“I’ve never imagined such hard-pressed days life would offer. I don’t know what the future holds for us, but all I can say is that I don’t have the capacity to restart the coaching centre,” said Rahim, in a choked voice.

Rahim’s story is the bewildering reality for thousands of people in Bangladesh who either lost work opportunities overnight or saw their earnings drop drastically in the pandemic-induced economic downturn.

Although restrictions were lifted gradually and economic activities started picking up, the much-aspired rhythm is still awaited with no one knowing for sure when it will return.

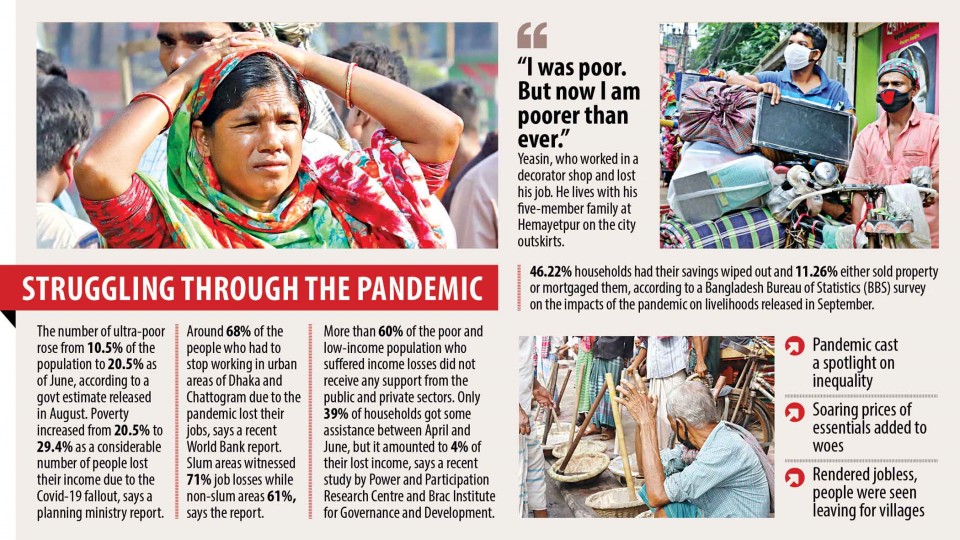

According to a planning ministry report released in August last year, the number of ultra-poor rose from 10.5 percent of the population to 20.5 percent as of June.

It said poverty increased from 20.5 percent to 29.4 percent as a considerable number of people lost their income due to the Covid-19 fallout.

Due to Covid-19, dependency of a large number of these affected people shifted from savings to loans and grocery credit to meet food needs.

A Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) survey on the impacts of the pandemic on livelihoods released in September said 46.22 percent households had savings wiped out and 11.26 percent either sold property or mortgaged them.

Adding to their woes, prices of essential food items namely rice, onions, potatoes and vegetables soared. Prices of the coarse rice consumed mainly by low-income and budget-conscious families rose by 45 percent to Tk 45-47 per kg in Dhaka city on December 31, from Tk 30-34 a year back, data by the Department of Agricultural Marketing showed.

But behind these economic stats, there are personal stories of loss, pain, isolation, frustration, tearful despair, unemployment, hunger, homelessness and renewed struggle.

The human toll aside, the pandemic cast a spotlight on the country’s inequality with well-heeled citizens able to hibernate safely at home while watching the exodus of a large number of poor and low-income people.

These people left the city and sought refuge in villages because of the income loss, deepening burden of house rent, utility expenditures, and ever-increasing prices of essentials.

Some of those have and will come back. But, for many, a return is uncertain. For now, at least, falling incomes and the high cost of living have made it impossible to stay in the capital city.

Dalim Fakir is one of them.

A manager of a tours and travel agency, he left Dhaka for his Bagerhat home in late July after the branch of the agency was closed down in the absence of business. He had four month’ unpaid house rent in Dhaka when he left.

But the turnaround attempts that the breadwinner of a four-member family made after his return also failed.

Initially, he tried to do business of supplying garments to stores in the district town. But as operators of clothing shops there buy apparel on credit, Dalim found his capital blocked amid sluggish recovery.

He then tried to market tea among tea vendors, only to find that businesses which sell tea had slashed buying prices — making it just equal to his purchase prices of the leaf.

Dalim had to surrender. By this time, all his capital — which was nearly Tk 50,000 when he returned home — was almost finished. And the support from his relatives also stopped.

“I am planning to come back to Dhaka to give a try again. But I have no capital to start anything,” said a frustrated Dalim.

While Dalim is planning to start all over again, Md Selim has been trying his luck in a completely different arena.

Every morning, the 42-year-old calls out to people to take breakfast in a makeshift small shop that sells tea and snacks on the footpath in the West Karwan Bazar area.

After working as an assistant accountant at a mega shopping complex for 14 years, he one day found himself in the list of job cuts during the shutdown.

“I was devastated initially,” said Selim, who provides for a five-member family.

After trying various things for a few months, he invested a portion of the benefits he got after losing his job in this footpath stall, targeting customers who are mainly on the lower rung of society.

“It’s been over two months, but I haven’t got any profit from my venture as almost all my earnings go towards paying rent and buying materials,” he said.

Apart from monthly Tk 6,000 rent, he pays a lump-sum amount to his assistant.

“Life is and will not be the same again. But I have to strive for my family,” he said.

But for workers in the informal sector, the situation has been dire. For them, the pandemic meant no job and no unemployment benefits or other protection. They could hardly have any savings.

So, before the pandemic it was a daily battle, yet Rubiya Begum and her eldest sister Sufia Begum would together earn around Tk 7,000 per month as domestic help in the Bhasantek area of the capital.

Abandoned by her husband long ago, Rubiya started living in one room in Bhasantek slum with her sister and their nephew, Sajib, whom she was raising after his mother’s death seven years ago.

She would work in three different households while Sufia worked in one. With the leftovers they used to get from house-owners, things were going well.

But the coronavirus shattered everything. Although she got food assistance in April and May from the government and charity organisations, that too stopped in June. She stopped paying the monthly rent — Tk 1,800 — for five months.

“We were being rendered jobless and utterly helpless. We did not get enough to eat,” said Rubiya, who hails from Kishoreganj.

With no options left, she had to take loans.

As things started to get back to normalcy, she managed to work in two households in September, albeit part-time. She is now earning Tk 2,500 a month. Sufia, however, could not join her work yet.

Rubiya said Sajib used to study in a local madrasa before the pandemic, but two months ago she got him a job in a tailoring shop where he gets Tk 2,000.

“Sajib’s mother wanted her son to study. But how could we do that when we’re struggling to make ends meet?” she said.

Her story is the same as thousands of workers, especially women, in the informal economy. Low-income groups including day labourers and rickshaw pullers were badly affected as they instantly became jobless due to the nationwide shutdown.

Although the stimulus packages announced by the government to absorb the economic shock, enormously supported export-oriented and big industries, a large number of low-income people and informal labourers were left behind.

More than 60 percent of the poor and low-income population who suffered income losses in this crisis did not receive any support from the public and private sectors, according to a recent study.

The study conducted jointly by Power and Participation Research Centre and Brac Institute for Governance and Development said only 39 percent of households got some assistance between April and June, but it amounted to 4 percent of their lost income.

A recent World Bank report said around 68 percent of the people who had to stop working in urban areas of Dhaka and Chattogram due to the pandemic have lost their jobs.

Slum areas witnessed higher — 71 percent — job losses than non-slum areas where it was 61 percent, said the report, titled “Losing Livelihoods: The labour market impacts of Covid-19 in Bangladesh”.

There were some steps to provide cash and food to the needy through government and private initiatives, but that was insignificant considering the extent of havoc Covid wreaked on lives and livelihoods.

Mohammad Yeasin can be considered luckier as he at least did not lose his job.

But the decorator business employee did not earn a single taka in over two months of shutdown that suspended all social gatherings and ceremonies. Even with the restrictions eased, the 38-year-old saw his earnings fall to almost nothing.

“I was poor. But now I am poorer than ever,” said Yeasin, who lives with his five-member family on the city outskirts at Hemayetpur.

Before the pandemic, he said, he would work for three to four days a week. Working each day would fetch him Tk 800 apart from the tips and free food at the ceremonies.

But now he can work twice a week and sometimes only once, making it difficult to earn a living, said Yeasin, who hails from Barishal. He said his wife took loans worth around Tk 1 lakh from her village, but now they cannot pay the instalments.

“On one hand, there’s pressure from lenders and there is quarrels and mental agony on the other,” he said.

“We can’t carry on like this. If things don’t improve, we may have to go to our village home,” he added, in a voice tinged with sadness and helplessness.

*his real name withheld on request