The good news is, in multicultural Australia, the Fraser Annings are on the wane and the Will Connollys are winning, writes Professor Adil Khan.

On 15 March, an Australian right-wing extremist went on a shooting rampage at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand where Muslims – men, women and children – gathered for their weekly special Jumma (Friday). The attack killed 50 people while praying. The attacker used semi-automatic weapons and live streamed the attack.

As the news of the massacres emerged, the New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern appeared live on television and promptly termed the massacre a “terrorist attack”. She described the mass shootings at two mosques in the city of Christchurch as “one of New Zealand’s darkest days”.

In her report on the massacre to the Parliament, Ardern described the perpetrator as, “a terrorist, a criminal and an extremist” and in utter contempt of the heinous act, she said that from here on, “you will not hear me utter his name”.

She also promptly moved to take measures to ban private possessions of military-type assault weapons and curb racism in New Zealand.

Other world leaders did indeed join in condemning the attack in the strongest of terms, though some have been observably less forthcoming than others. For example, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been less circumspect. He condemned the “heinous terrorist attack in places of worship” while avoiding to utter the words, “mosques” or “Muslims”. This is disappointing though not unexpected of a man and a regime that openly promote a brand of politics known as Hindutva, which is abjectly sectarian or, more candidly, anti-Muslim.

In Australia, condemnations have been immediate right across the board. In Brisbane where I live, local Muslims organised a special prayer for the deceased and their families, where thousands of people representing all faiths, attended (organisers made arrangements of 1,500 but more than 6,000 turned up). Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk also attended and spoke at the gathering.

One Nation Leader Pauline Hanson did condemn the terrorist act but it appears to have been a tongue-in-cheek response.

In an interview with Hanson on Sunrise, David Koch suggested One Nation was complicit in the rise of anti-Muslim racism in Australia and said:

This (accused Christchurch shooter Brenton Tarrant’s) terrorism manifesto almost reads like One Nation’s immigration and Muslim policy.”

Hanson responded by expressing “sympathy for the victims of the Christchurch attack” but, in the same breath, she referred to Muslim immigration as the problem because,

“I don’t like Sharia Law, genital mutilations etc etc.”

Fair enough, but what has Sharia Law and genital mutilations got to do with Muslim immigration? After all, when Muslims migrate to Australia they do not migrate to an Islamic state. They migrate to Australia knowing that it is a secular country and that to live and operate here they would have to abide by these laws. Therefore, Muslim immigration to Australia does not make Australia Islamic but makes Muslims secular.

Besides, the aspects of Muslims that Hanson dislikes and claims contradict Australian values and customs, are practised by only a handful — and these rituals are also not observed in most Muslim-majority countries from which they emigrate. Hanson needs to get her facts right before she misinforms and misguides unsuspecting Australians.

Following Hanson’s line of thought, Independent Senator Fraser Anning wasted no time in linking the Christchurch terrorist act to “Muslim immigration”.

However, the good news is that Hanson and Anning are in the minority and have failed to convince most Australians. In fact, they have annoyed most such that at one of Anning’s recent press conferences in Melbourne, a 17-year-old boy, Will Connolly, interrupted his speech and cracked, as a show of protest, an egg on the back of the Senator’s head.

In an instant, Connolly became a hero and his egg-trashing image has hit the world media as the symbol of protest against racism. Two murals have since popped up in Eggboy’s honour, in Hosier Lane, Melbourne, by street artist, Van, and Sydney’s Lord Gladstone pub, by artist Scott Marsh.

Eggboy who, by breaking the egg on Anning’s head, may also have broken public harassment law may still be charged. This has prompted an appeal in social media to raise funds to pay for his legal costs. People have chipped in enthusiastically and have so far raised almost $80,000. In the meantime, Connolly’s lawyer, Peter Gordon, has announced that he and his team are fighting the case, pro bono.

Connolly, whose egg-smashing image has become a symbol of anti-racism, has announced that he is not going to keep the money but donate the entire amount to the families of the victims of Mosque massacres.

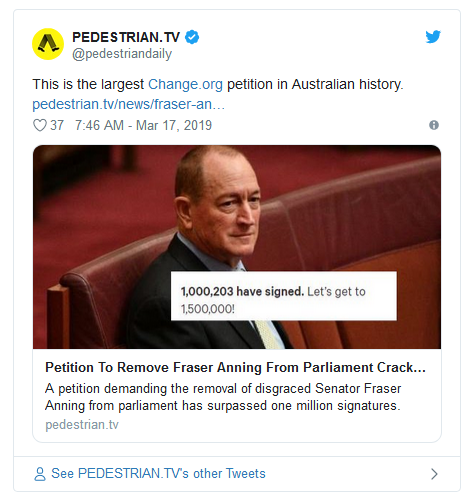

Other developments relating to Anning’s statement are that more than 1.4 million Australians have signed a petition calling for him to be expelled from the Parliament. Both the Labor Party and the Coalition have announced they ‘plan to vote together to censure [Anning] in a Senate motion when MPs return to Canberra in April’.

This is overwhelmingly heartening news.

However, I would like to recount a personal experience of mine to show how Australia has changed over the years, for the better.

Three decades ago, I was travelling from Tokyo to Brisbane and sitting next to me was someone whose name I have forgotten — let us call her Jane. Jane was a columnist for the Sydney Morning Herald. As we started to chat, one thing led to another and finally, we came to discussing the subjects of multiculturalism and ethnic integration in Australia.

In order to highlight where we stood in terms of multiculturalism at that time, I shared with her a personal experience of mine:

It could be 1992 or 1993. I was visiting Jakarta, Indonesia as the team leader of an AusAid evaluation mission and it so happened that our mission coincided with Australia Day celebrations at the Australian Embassy. The Embassy knew of our presence and invited us, the evaluation team, to the reception where I somehow got involved chatting with a middle-aged woman with a strong English accent.

We would have talked for about 15 minutes when the following exchange occurred:

WOMAN: By the way, Mr Khan, what nationality are you?

AK: Australian.

WOMAN: But you don’t look like an Australian.

AK: I appreciate your confusion, I am not dark enough.

I then turned to Jane and told her:

You see, as long as people would look at me and say that I do not look like an Australian, I would infer that Australia’s multiculturalism is not working.”

Jane then said, “Mr Khan, how about I share one of my own personal experiences on this issue?”

She told me that one day her seven-year-old son, Paul, told her,

Mum when you come to pick me up this Friday, I may not be there. I shall come home with another friend but could you pick up my friend, John, whom you have not met, who will be wearing a red cap and bring him to our home? John and my other friend will be spending the weekend at our place.

Accordingly, Jane went to the school, saw John in a red cap, picked him up and brought him home, and the kids had a great time during the weekend. After dropping John and her son’s other friend at their respective homes, on the trip home Jane asked her son,

“Paul, I just don’t understand, there could have been a hundred other kids in that school with a red cap on, why did you not tell me that John is a black kid?”

Jane said her son looked at her in bewilderment and said:

“Is he?”

The good news is that these days, in Australia, the Fraser Annings are on the wane and the Will Connollys are winning!

Professor Adil Khan is an adjunct professor at the School of Social Sciences, University of Queensland and a former senior policy manager of the United Nations. Adil is also a member of the Rohingya Support Group, Queensland.

This article was published in Independent Australia on March 26, 2019