Prothom Alo

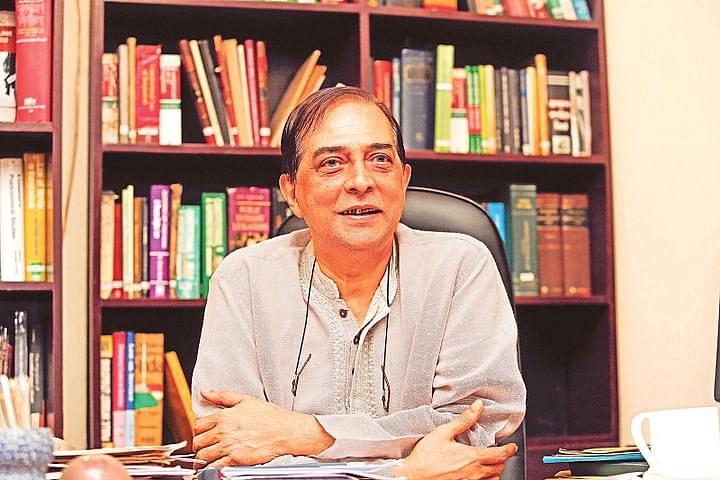

Shahdeen Malik has been a lawyer with the Supreme Court since 2000. He began his career in 1980 as a lecturer in the law department of Dhaka University. In the nineties he worked in the NGO sector. His articles have been published in legal reputed journals at home and abroad. He has taught at BRAC University, University of Asia Pacific and Gono Bishwabidyalay (University). He has law degrees from Moscow, Philadelphia and London. On the occasion of World Press Freedom Day, this reputed lawyer talked to Prothom Alo at length about the media in Bangladesh, the Digital Security Act and freedom of speech.

How much freedom has our constitution given the media and what is the actual situation on ground?

Our constitution hasn’t fully ensured freedom of expression or press freedom. Certain laws pertaining to state security, public discipline, ethics, civility and other factors have given the parliament the power to control press freedom. The laws that place certain restraints on the media, should be fair and justified.

The defamation clauses in the Digital Security Act (sections 21, 25, 28, 29, 31) have undoubtedly been excessively restraining to the media. These sections have been drawn up in a manner that any statements can be construed to be a violation of the law. Arrests can even be made in this regard. The so-called accused can be placed behind bars for extended periods of time. And I do not know why the judges in recent times have not been granting bail easily in these cases. That is why journalists often hesitate to practice freedom of press to the full extent. In fact, many take a step back from this freedom.

It has been 50 years since independence. There have been military and civilian governments and even hybrid democratic government. When do you think the news media has faced the most difficult times?

Things have not been easy under any government for the media. It was most difficult both in the seventies when almost all newspapers were shut down and also now because of the Digital Security Act. At present innumerable cases are being filed in police stations all over the country for just a statement, a report or a post. All these days I had known that there can be just one criminal case for one incident. This has been the rule for around 200 years, but over just the last two years, this has changed completely. You will recall that Barrister Mainul Husein had to face around 20 cases in various areas simply for using one particular word on a TV talk show. Such a deluge of cases is certainly the eighth wonder of the legal world.

In recent times, however, journalists have been curbing their own freedom to an extent. With just a couple of exceptions, almost all newspapers, media houses, TV channels and news portals are owned by business houses. Businessmen have steadily been making inroads into both the parliament and the media, in throngs. While there are exceptions, business interests undeniably curb press freedom.

Certain laws are a serious obstacle to free media and, in that sense, are contrary to the spirit of the constitution. How do you view this?

There are definitely laws that go against press freedom. At the same time, other than the laws, fluctuations in democratic awareness, in the spirit of independence, awareness of one’s rights and blind support for certain political parties, etc. can also restrict freedom of speech. Officially speaking our democracy may be 50 years old, but in the real sense it is much less. That is our collective failure. And taking advantage of this failure, laws are drawn up to restrict freedom of speech further.

It must also be kept in mind that the lower courts are still under the law ministry’s control and the appointment of judges to the upper courts are often guided by political views and ideology. We see nowadays that the higher courts even confiscate books. In the past, if the government confiscated any book, the injured party could resort to the court to fight for his rights.

A recent report of Reporters without Borders said that Bangladesh is right at the bottom of the press freedom index in South Asia. Why is this so?

This is so shameful! A country of extreme communalism like Afghanistan and a country ruled by monarchy like Bhutan, are even above us in the index. We rank at 152 in the World Press Freedom index of Reporters without Borders. To get an idea of our situation, we can look at the countries that rank below us. With a few exceptions, these countries are either monarchies or by a person who has been in power for a quarter of a century, ‘winning election after election’.

In 2009 when the Right to Information Act was passed, it seemed to be a step forward for journalists to get information. But neither government institutions nor private ones are willing to provide information. What can be done?

There are all sorts of commissions nowadays simply to accommodate persons of one’s own camp. There are, of course, a few exceptions. However, in most cases the objective of these commissions is to create various posts. So it would be foolhardy to expect anything from these commissions.

The rights to information given to journalists by the Right to Information Act, were snatched away by the Digital Security Act. If two laws are in contradiction, which one should be given priority?

The latter law is given priority over the former. The Right to Information Act came in 2009. Nine years later in 2018, the Digital Security Act was enforced and so the 2018 law will get priority over the one of 2009.

The Digital Security Act has so broadly defined various statements as punishable offences that it is the most effective system to accuse anyone for statements that they make. Propaganda and publicity can be an offence. But there is no specific criteria as to what statement or words of a journalist can be construed as propaganda or publicity.

In another section, certain types of misleading publicity are considered to be an offence. The problem, which type of publicity is misleading, which type is acceptable, which type is unacceptable – nothing has been defined. That is why in countries where there is democracy and freedom of speech, publicity, propaganda, etc are not defined as offences. There is an exception. If any misleading propaganda or publicity leads to the committing of crime, such as the arson, violence and damages in Brahmanbaria towards the end of March, this will be considered an offence. I feel that the Digital Security Act defines various statements as offences simply to curb freedom of speech, and the government has done this knowingly.

A large portion of the cases filed under the Digital Security Act are against journalists. Many have been harassed and tortured. Do journalists have any scope for legal recourse in this regard?

No. There are two sides to the Digital Security Act. One is to define cyber crimes and to determine the penalty for these offences. And the other is to spread fear and put journalists behind bars, restricting press freedom to any extent. And as the objective of this law is to restrict press freedom, a reign of terror will continue for as long as this law exists. The empty promises made by the minister that this act would not be used against journalists, will remain empty promises.

The India government recently passed a law curbing freedom of expression. The Supreme Court there abolished the law. Can we hope for any such verdict from our Supreme Court?

There is no harm in hoping, but only time will tell whether those hopes will come true.

Freedom of the press also involves freedom of expression and other democratic rights. Can there be press freedom in the absence of democracy?

Certainly not. As democracy here is very limited, so is our press freedom. You cannot expect press freedom in the monarchies of the Middle East. Egypt is a country that ranks below us in the press freedom index. They have such an ancient civilisation, with their pyramids, mummies and such. In their 3000-year history, there has been only once a democratic, free and fair election. The president elected in that election was sentenced to life imprisonment and died in prison.

If a citizen breaks the law, the state takes legal action against him or her. If the state violates the law, can a citizen take legal action?

Yes, of course. These are known as writ petitions. However, these are sensitive and complicated cases. Nowadays we often see people filing writ petitions. If the arguments of the case are weak and the judge scraps the case, then it will be difficult to get legal recompense for the concerned wrongdoing. So if a writ petition is filed without adequate study, consideration, preparation and research, it can backfire. So while there is scope to resort to the law, this must be done with extreme care and sound preparation.

The government has used all sorts of excuses during the coronavirus outbreak to further curb the right to information. How can this right be revived?

Many less democratic countries are using coronavirus as an excuse to curb press freedom and our government is hardly an exception. As the coronavirus pandemic is not going away anytime soon, it is feared that our journalism will get more used to restricted freedom. The people will further lose awareness of their rights and the government’s lack of accountability will increase. I am sorry not to have been able to give any words of hope.

Thank you

Thank you

*This Interview appeared in the print and online edition of Prothom Alo and has been rewritten for the English edition by Ayesha Kabir