How a Mohammad Statue Ended up at the Supreme Court

The other day, Will and Jason told me about a Mohammad statue at the Supreme Court they heard about on This American Life. This was their way of saying, “We’re curious, so you should go do a bunch of research on it. Let us know how that goes.”

When I hear about depictions of Mohammad, I picture Muslims burning Aqua* CDs in the streets and boycotts of Danish”¦danishes.

But much to my surprise, the Danes aren’t to blame this time around. The statue in question is, in fact, right in our very own Supreme Court building.

Let’s start at the beginning.

A Court to Call Home

Despite its stature in the country’s political and cultural landscape, the Supreme Court was something of a vagabond in its early years. When New York City was our capital, the Court met in the Merchants’ Exchange Building, and when the capital moved to Philadelphia in 1790, the Court set up shop in Independence Hall, and then City Hall. When the federal government went off to Washington, the Court used the Capitol Building as a flophouse, but got bounced to a new chamber six different times during their stay.

Finally, in 1929, Chief Justice William Howard “I got stuck in the White House bathtub” Taft decided enough was enough and persuaded Congress to authorize the construction of a permanent home for the Court. Construction on the Supreme Court Building was completed in 1935, and the Court finally had a home to call its own after 146 years of existence.

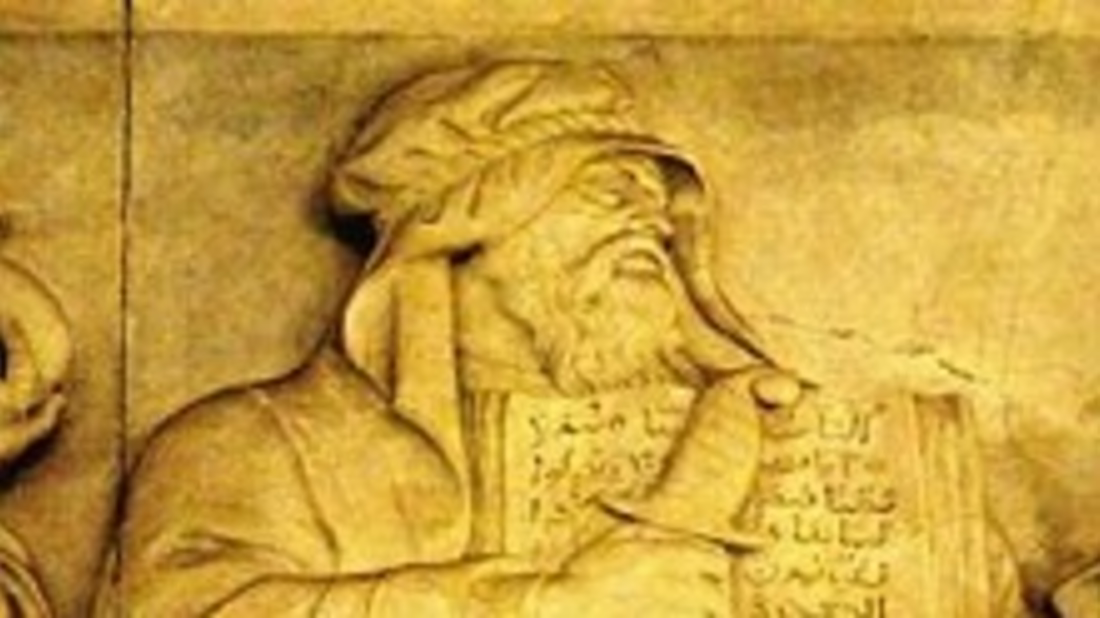

Sculpture figures prominently in the Corinthian architecture of the Court Building. One chamber features a frieze decorated with a bas-relief sculpture by Adolph A. Weinman of eighteen influential law-givers. The south wall depicts Menes, Hammurabi, Moses, Solomon, Lycurgus, Solon, Draco, Confucius and Octavian, while the north wall depicts Napoleon Bonaparte, John Marshall, William Blackstone, Hugo Grotius, Louis IX, King John, Charlemagne, Justinian and, you guessed it, Mohammad.

Objections

Things were all well and good for a few decades, with no documented controversies over the sculpture that I could find. But then, in 1997, the fledgling Council on American-Islamic Relations brought their wrath to the Court, petitioning then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist to remove the sculpture. CAIR outlined their objections as thus:

1. Islam discourages its followers from portraying any prophet in artistic representations, lest the seed of idol worship be planted.

2. Depicting Mohammad carrying a sword “reinforced long-held stereotypes of Muslims as intolerant conquerors.”

3. Building documents and tourist pamphlets referred to Mohammad as “the founder of Islam,” when he is, more accurately, the “last in a line of prophets that includes Abraham, Moses and Jesus.”

Rehnquist dismissed CAIR’s objections, saying that the depiction was “intended only to recognize him [Mohammad] … as an important figure in the history of law; it was not intended as a form of idol worship.” He also reminded CAIR that “words are used throughout the Court’s architecture as a symbol of justice and nearly a dozen swords appear in the courtroom friezes alone.”

Rehnquist did make one concession, though, and promised the description of the sculpture would be changed to identify Mohammad as a “Prophet of Islam,” not “Founder of Islam.” The rewording also said that the figure is a “well-intentioned attempt by the sculptor to honor Mohammed, and it bears no resemblance to Mohammed.”

The reasoning behind Rehnquist’s rejection? For one, he believed that getting rid of any one sculpture would impair the artistic integrity of the frieze, and two, it’s illegal to injure, in any way, an architectural feature of the Supreme Court Building.

Other Depictions of the Prophet

While the Qur’an forbids idolatry, it doesn’t expressly forbid depictions of the Prophet. The prohibition on such depictions that we often hear about comes from hadith (oral traditions that supplement the Qur’an). Muslim groups have differing opinions on the prohibition, with Shi’a Muslims generally taking a more relaxed view than Sunnis. That said, there are more depictions of Mohammad in art out there than we’d think, from the US to Uzbekistan. Until the 1950s, there was even a statue of the Prophet at the Manhattan Appellate Courthouse, right on the front steps.

The article appeared in the https://www.mentalfloss.com on 11 January 2008